PRIVATE-PUBLIC PARTNERSHIPS FOR

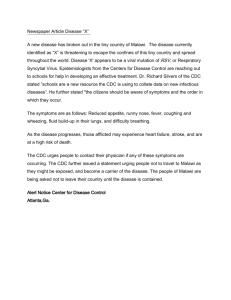

advertisement