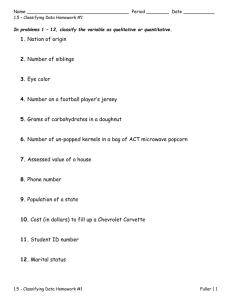

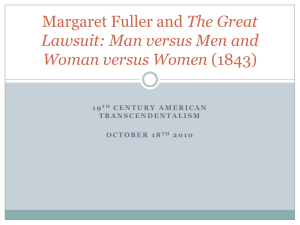

TAMPEREEN YLIOPISTO Gender Trouble in Margaret Fuller's

advertisement