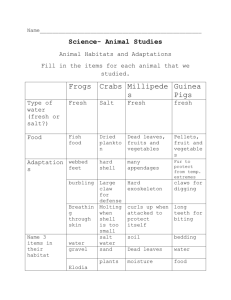

Fresh Press Kit_0511_ext

advertisement

A R ippl e Eff ect In c. R el eas e 72 mi nutes 56 mi n utes ( Bro adca st v ersi on) Medi a C on ta ct: Crystal Cun Crystal@ FRE S Hthemovi e.c o m (347) 860 -9444 http:// w ww. F RE S Hthemo vi e.c o m FRE S H celebrates the farmers, thinkers and business people across America who are re-inventing our food system. Each has witnessed the rapid transformation of our agriculture into an industrial model, and confronted the consequences: food contamination, environmental pollution, depletion of natural resources, and morbid obesity. Forging healthier, sustainable alternatives, they offer a practical vision for a future of our food and our planet. Among several main characters, FR ES H features urban farmer and activist, Will Allen, a 2008 recipient of the MacArthur “genius” grant and recently named one of Time’s 100 most influential people; sustainable farmer and entrepreneur Joel Salatin, made famous by The Omnivore’s Dilemma, the best-selling book by Michael Pollan, who is also featured in the movie; and, Kansas City supermarket owner David Ball, who is challenges our Wal-Mart-dominated economy every day by stocking his stores with products from local suppliers. Dir ector’s Statement I first started thinking about making FRE S H after reading a three-part article in the New Yorker about global warming four years ago. The article’s dire exposé of the complexity and extent of the problem left me feeling like a powerless and hopeless observer, watching the world spiraling towards its inevitable destruction. I also realized that these very feelings were responsible for my inaction. But in the face of such large and complex problems, it was hard to see how my small, seemingly inconsequential, individual actions could have meaning or impact. So I embarked on the making of FRE S H to see if, yes, they do in fact matter. Initially, I intended to document the urgency of the global warming crisis, hoping to scare others and myself into taking action. Instead, I encountered the most inspiring people, ideas and initiatives. Who knew that we already had the solutions to so many of our problems and that some of us were already hard at work implementing them? Instead of the despair and inaction unwittingly fostered by the media, these examples of change suggested a very different perspective. Life is an indivisible network in which every node is critical. Each one of us is creating the world we are living in. It is this creative process that gives our life meaning and pleasure. It is precisely the transformation from inaction to empowerment, the very transformation I went through making the film that I want the film to offer to audiences. I want audiences to engage by discussing the issues, finding out what’s going on in their community and getting involved. FRE S H portrays a movement that is happening in America and worldwide. The alternative food market is the fastest growing market in the United States, even though it still makes up a minuscule percentage of the food economy. And it’s incredibly energetic. Where it will lead us, I don’t know. Lin Yutang, a Chinese writer and inventor, said that “Hope is like a road in the country; there was never a road, but when many people walk on it, the road comes into existence.” I like to remind myself that both cynicism and optimism are equally righteous. We don’t know what the future holds, yet we can remain hopeful in the knowledge that change is always possible, even when it is hard to imagine, and all of us can choose to participate in it. 2 A B OU T T HE F I LM FRE S H is more than a film; it is a reflection of a rising movement of people and communities across America who are re-inventing our food system. FR ES H celebrates the food architects who offer a practical vision of a new food paradigm and consumer access to it. Encouraging individuals to take matters into their own hands, FR ES H is a guide that empowers people to take an array of actions as energetic as planting urban gardens and creating warm composts from food waste, and as simple as buying locally-grown products and preserving seasonal produce to eat later in the year. Throughout the film, we encounter the most inspiring people, ideas, and initiatives happening around the country right now. At the Growing Power urban farm in Milwaukee, Will Allen is turning three acres of industrial wasteland into a mecca of nutrition for his neighborhood. In Kansas City, we witness David Ball revitalize his community, turning the modern concept of the Supermarket on its head by stocking his stores with produce from a cooperative of local farmers. And, we journey to Joel Salatin’s farm in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley to witness his methods for closing the nutrient cycle, allowing cows, chickens, pigs and natural grasses to flourish and produce without ever an ounce of chemical fertilizer or industrial animal feed. FRE S H tells the stories of real people, connecting audiences not with facts and figures or apocalyptic policy analysis, but with examples of personal initiative and concrete ways to engage in a new food model. 3 W H AT F OL KS A RE S A YI NG A BO U T FRE S H FRESH is a bra ci n g, ev en exhi lara ti n g look at the whole range of efforts underway to renovate the way we grow food and feed ourselves. – Mi c ha el Po lla n FRESH is just that—an up beat a n d wo nder full y f res h look a t o ur foo d s ys tem and how to make it work better for the health of humans and the planet. It’s a must see for everyone who eats. – Mar io n N es tl e We all just watched FRESH…and we were mesmerized and empowered. Ev er y Ameri ca n needs to see thi s. You will capture hearts with this. I can’t wait to sit in an audience watching this. It is absolutely masterful. – Jo el Sal atin If Foo d I nc . was yo ur wak e up call, Fr es h, T he Movi e is your call to a ctio n. Fresh’s strength is that it shows the incredible creativity of individuals who are devoting their lives to producing food differently. – E coS alo n Where FRESH departs from Food Inc., The Omnivore’s Dilemma, and most other food documentaries of late, is that FRE S H is do w nri ght ho peful . – Fai rFoo dFi ght. co m FRESH is a ri c h a n d i nsp iri n g meal . FRESH offers not only a serious look at where we are and a useful primer on how we got here, but r ep ea ted hea r t-l if ti n g demo ns tra tio ns that there are ways to produce food that are safer, kinder and more natural. FRESH provides not only education but inspiration—and hope. – J oa n Gusso w 4 T H E FRE S H M OV EM ENT I S G ROWI NG FRESH is a documentary that celebrates the farmers, thinkers and entrepreneurs across America who are re-inventing our food system. FRESH is also a movement: an activist platform that integrates screenings with grassroots outreach, spreading awareness and sparking action through advocacy campaigns, petitions and social networking. Here are some of our achievements: • • • • • Successful Self-Distribution. Since our initial release in May 2009 with an 11-city US tour, FRE S H has s cr een ed ov er 4,000 ti mes aro un d the worl d. This accomplishment was 100% grassroots-driven, with contributions from no more than two paid staff at any given time. Longevity & Financial Sustainability. Our activist outreach has allowed us to sustain interest in FRESH for almost two yea rs. All of our activities have been financed through the licensing of FRESH screening rights and community sales. Partnerships with Key Organizations. Our distribution and outreach strategy has helped us develop a network of hun dr eds of p ar tn er or ga ni z ati on s. FRESH works closely with partners to generate ideas about how FRESH can best serve local communities, from tying screenings to campaigns to organizing post-screening panel discussions. Ultimately, these participatory events help audience members become i mmedi atel y an d mea ni n gf ull y invo lved i n the s us ta in abl e f oo d movemen t in their o w n ba ck yar ds. Powerful Online Activist Platform. Our innovative distribution and activist platform (based on Salsa Software developed by Democracy in Action) has allowed us to develop exciting and relevant a dvo ca c y ca mp ai gns. These campaigns have brought important issues in food policy to the attention of our supporters and asked them to take action (sign a petition, call their representative, etc). Thus far, we’ve gathered over 60,0 00 s i gn atur es to submit to various federal agencies, regarding issues ranging from genetically engineered salmon to antitrust enforcement for farmers. Growth of Social Networks. Through our unique combination of grassroots outreach, online campaigning and social media communications, we have cultivated an online community of over 70,00 0 p eo ple. Our Facebook fan base alone is over 19,0 00 peo pl e and has a mo n thly gro wth ra te of 10 % due to our relevant and informative content. Recent survey results suggested that 50% of the members of the FRESH community have not actually seen FRESH yet. This as a testament to the value of FRESH beyond the film itself - i t’s mo re than a doc umentar y; i t’s a movemen t. 5 T H E FRE S H F O OD M ODEL I N A C TIO N Env iro n men tall y & E co no mic all y S ustai nab le Agr ic ul ture: Jo el Sala ti n ’s Po lyfa ce Far m Polyface Farm was 400 acres of badly eroded land in rural Virginia when Joel Salatin started farming it 30 years ago. Government and private consultants advised him to graze the forest and build feedlots, but Joel saw the negative impact this kind of farming was having on the land, the animals, the farmers, and the community. So following his deeply held values and foregoing government assistance, he developed a self-sustaining organic farm. By rotating the use of his land, Salatin allows his cattle to feed only on grass, thus closing the nutrient cycle. Rotating cattle allows the grass to regenerate, therefore capturing more CO2 and building more soil. The cow manure that’s produced is then used to fertilize his soil, eliminating the need to buy synthetic fertilizers or to manage a toxic manure lagoon. The cows are followed in rotation by chickens, who eat fly larvae out of the dung, thereby “sanitizing” the fields and eliminating the need for antibiotics. Salatin’s ingenious system of farming combines ecology and technology in a way that increases productivity while respecting the land and animals, demonstrating that a farmer can be both economically and environmentally sustainable. Revi tal iz in g o ur L oc al E co no mi es: D avi d Ba ll’s Alter na tiv e S up er mark et With the arrival of Wal-Mart and other corporate supermarkets in the 1980s, David Ball watched his family-run Kansas City supermarket chain fail, alongside a once-thriving local farm community. To save his business, Ball turned to his community and proposed a simple but out-of-the-box solution: Ball helped organized a cooperative of local farmers — The Good Natured Family Farm — and aggressively marketed their products in his 18 supermarkets. This decision has revitalized not only Ball’s own business, but also has created a ripple effect of economic vitality to rural areas while improving the access to healthy foods in Kansas City. Heal thy Foo d F or AL L: Will All en ’s E duc ati onal Urb an Far m Fifteen years ago, Will Allen bought a piece of abandoned land in the heart of Milwaukee. Today, these three acres have become Growing Power, an oasis in an otherwise neglected neighborhood. The farm turns over one million pounds of the city’s waste into fertile soil, which in turn produces one million pounds of chemical-free food every year. As a result, Allen makes fresh food — from organically grown vegetables to his farm-raised tilapia — available every day in a community where once there was none. The farm has created jobs, bolstered nutrition, aided small farmers, and fought hunger in one of the poorest neighborhoods of Milwaukee — all while demonstrating a practical, cost-effective alternative to the nation's dysfunctional food system. The stories of these incredible innovators have been carefully selected and provide practical, on the ground, solutions, that can inspire each on of us to become active participants in shaping the future of the planet. To learn more about growing, living and eating FRE S H, visit: www.FRESHthemovie.com 6 A NA ’ S 10 FRE S H S O LU TIO NS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Buy loca l pro duc ts when possible, otherwise, buy organic and fair-trade products. Ask your grocer or favorite restaurant what local food they carry and try to influence their purchasing decisions. You will support your local economy and small farmers, reduce your exposure to harmful pesticides, improve the taste and quality of your food, and protect the environment from fertilizer and pesticide run-offs. Shop a t yo ur lo cal far mer s mar ket, joi n a CS A (Community Supported Agriculture) and get weekly deliveries of the season's harvest, and by buy from local grocers and co-ops committed to stocking local foods. Suppor t r es ta ura n ts a n d foo d v en dors tha t b uy lo call y p ro duc ed foo d. When at a restaurant, ask (nicely!) your waiter where the meat and fish comes from. Eventually, as more and more customers ask the same question, they'll get the message! Avo i d G MOs (Genetically Modified Organisms)! When buying processed food (anything packaged) buy organic to avoid GMO. (Since almost all the soy, corn, and canola in the US is genetically modified, over 70% of all processed food contain GMOs from by-products of these grains.) CO O K, C AN, D RY & FR EE ZE ! Our culture has forgotten some of the most basic joys of cooking. Not only is cooking at home better for you and more economical, but it's an invaluable skill to pass on to your children. Dri nk pl en ty o f wa ter, b ut av oi d bo ttl ed wa ter when you can. Water bottles pollute the environment and bottled water is often mere tap water. Plastic is harmful to your health and to the environment. Buy a reusable water bottle and invest in a good water filter. Gro w a gar den, visit a farm, volunteer in your community garden, teach a child how to garden. GET DIRTY! Have fun! Volun teer and/or financially support an organization dedicated to promoting a sustainable food system. Stay informed by joining the mailing list of the advocacy groups you trust. Get i nvolv ed in yo ur co mmun ity! Influence what your child eats by engaging the school board, effect city policies by learning about zoning and attending city council meetings, learn about the federal policies that affect your food choice and let your congress person know what you think. S H AR E yo ur p ass io n! Talk to your friends and family about why our food choice matters. And organize a FRE S H screening! 7 H EA L T H B ENEFIT S OF E A TI NG FRE S H Pa stur e-rai sed mea t, eggs, a n d da ir y Low er f at: Meat, eggs, and dairy products from pastured animals are ideal for your health. Compared with commercial products raised on feed lots, they offer you more "good" fats, and fewer "bad" fats, according to the Journal of Animal Science, among others1. Because meat from grass-fed animals is lower in fat than meat from grain-fed animals, it is also lower in calories. As an example, a 6ounce steak from a grass-finished steer can have 100 fewer calories than a 6-ounce steak from a grain-fed steer, or the same amount as a skinless chicken breast. If you eat a typical amount of beef (66.5 pounds a year), switching to lean grass-fed beef will save you 17,733 calories a year. If everything else in your diet remains constant, you'll lose about six pounds a year. If all Americans switched to grass-fed meat, our national epidemic of obesity could diminish. Mo re V i ta min s: Meats from pastured animals are richer in antioxidants; including vitamins E, betacarotene, and vitamin C. Furthermore, they do not contain traces of added hormones, antibiotics or other drugs. According to a study by Colorado State University 2, the meat from the pastured cattle is four times higher in vitamin E than the meat from the feedlot cattle and, interestingly, almost twice as high as the meat from the feedlot cattle given vitamin E supplements. In humans, vitamin E is linked with a lower risk of heart disease and cancer. This potent antioxidant may also have anti-aging properties. Most Americans are deficient in vitamin E. More O mega-3s : Meat from grass-fed animals has two to four times more omega-3 fatty acids than meat from grain- fed animals, according to the Journal of Animal Science 3. Eggs from pastured hens can contain as much as 10 times more omega-3s than eggs from factory hens. Omega-3s are called "good fats" because they play a vital role in every cell and system in your body. A diet high in Omega three may reduce the risk of cancer4, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and heart disease. A study by Tashiro and Yamamori in Nutrition also found that people with a diet rich in omega-3s are less likely to suffer from depression, schizophrenia, attention deficit disorder (hyperactivity), or Alzheimer's disease.5 Mo re Co nj uga ted L in oleic Aci d: Meat and dairy products from grass-fed ruminants are the richest known source of another type of good fat called "conjugated linoleic acid" or CLA. When ruminants are raised on fresh pasture alone, their products contain from three to five times more CLA than products from animals fed conventional diets.6 CLA may be one of our most potent defenses against cancer.7 1 1. Rule, D. C., K. S. Brought on, S. M. Shellito, and G. Maiorano. "Comparison of Muscle Fatty Acid Profiles and Cholesterol Concentrations of Bison, Beef Cattle, Elk, and Chicken." J Anim Sci 80, no. 5 (2002): 1202-11.;Dhiman, Tilak R. "Factors Affecting Conjugated Linoleic Acid Content in Milk and Meat" Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 45 (2005), pp. 463-82: 467-68: 472. 2 "Dietary supplementation of vitamin E to cattle to improve shelf life and case life of beef for domestic and international markets." G.C. Smith Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523-1171 3 Duckett, S. K., D. G. Wagner, et al. (1993). "Effects of time on feed on beef nutrient composition." J Anim Sci 71(8): 2079-88. 4 Simopolous, A. P. and Jo Robinson (1999). The Omega Diet. New York, HarperCollins; Rose, D. P., J. M. Connolly, et al. (1995). "Influence of Diets Containing Eicosapentaenoic or Docasahexaenoic Acid on Growth and Metastasis of Breast Cancer Cells in Nude Mice." Journal of the National Cancer Institute 87(8): 587-92 5 Tashiro, T., H. Yamamori, et al. (1998). "n-3 versus n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in critical illness." Nutrition 14(6): 551-3. 6 Dhiman, T. R., G. R. Anand, et al. (1999). "Conjugated linoleic acid content of milk from cows fed different diets." J Dairy Sci 82(10): 2146-56. 7 Ip, C, J.A. Scimeca, et al. (1994) "Conjugated linoleic acid. A powerful anti-carcinogen from animal fat sources." p. 1053. Cancer 74(3 suppl):1050-4; Aro, A., S. Mannisto, I. Salminen, M. L. Ovaskainen, V. Kataja, and M. Uusitupa. "Inverse Association between Dietary and Serum Conjugated Linoleic Acid and Risk of Breast Cancer in Postmenopausal Women." Nutr Cancer 38, no. 2 (2000): 151-7. 8 Sustaina bl y G rown Fr uits & V eg etab les “According to the USDA’s own numbers if you look at fresh produce grown in 1950 and compare it nutritionally with fresh produce grown today you will find that the amounts of key nutrients, minerals and vitamins have diminished by 40%.” Michael Pollan, in F RES H. Mor e n utritious: Organic crops, on average, contain higher levels of trace minerals and antioxidant phytonutrients.8 Official food composition tables, including data compiled by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, reveal that since the 1940s the mineral levels in fruits, vegetables, meat and dairy have declined substantially in conventional foods. Combine this with earlier (pre-ripened) picking, longer storage, and more processing of crops — all of which result in a depletion of nutrient levels in produce — and it's no wonder we may be getting fewer nutrients in our food than we were 60 years ago. The artificial fertilization associated with conventional crops produces lush growth by swelling produce with more water. Partly because of this water inflation, there are higher levels of nutrients in organic produce. A recent review of the subject estimated that organic produce tends to contain 10-50% more phytonutrients than conventional produce. Phytonutrients, many of which are antioxidants involved in the plant's own defense system, are higher in organic produce because crops rely more on their own defenses in the absence of regular applications of chemical pesticides. No c h emica l r esid ue: One of the huge advantages of organic foods is that they haven't been doused in pesticides.9 Pesticide residues turn up, not just on fruit and vegetables, but in bread, baby food and other products. Monitoring programs consistently show that around one in three non-organic food samples tested contains a variety of pesticide residues. Most pesticide-residue safety levels are set for individual pesticides, but many samples of fresh produce carry multiple pesticide residues. Rules often do not take into account the "cocktail effect" of combinations of pesticides in and on foods. Research is emerging confirming the potential for such synergistic increases in toxicity of up to 100-fold, resulting in reproductive, immune and nervous system effects not expected from the individual compounds acting alone. One American peer-reviewed study lead by Chensheng Lu found that the urine and saliva of children eating a variety of conventional foods from area groceries contained biological markers of organophosphates, the family of pesticides spawned by the creation of nerve gas agents in World War II.10 8 Agronomy for Sustainable Development (2009), DOI: 10.1051/agro/2009019,“Nutritional quality and safety of organic food. A review”, Author: Lairon, D. Whether or not organic food brings nutritional benefits over conventional food has been a matter of considerable inquiry and debate. The UK’s Food Standards Agency (FSA) concluded that there is no evidence of nutritional superiority. More recently, however, a review published in the journal Agronomy for Sustainable Development has drawn different conclusions. 9 See list of resources from the Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/rr/scitech/tracer-bullets/pestfoodtb.html 10 Chensheng Lu's study was published in Environmental Health Perspectives (ehponline.org), a publication of the National Institute of Environmental Health Science. 9 10 E NVI R O NM ENT AL B ENEF IT S “It’s very seductive to hear that language: ‘we need to feed the world.’ When people in industrial agriculture talk about feeding the world, they are talking about increasing the production of grain and nobody is stopping and saying: well what are you using that grain for? Are you growing food? No! they're not growing food, those are seeds for cattle feed, for a very unsustainable system of fattening cattle on feedlots. But guess what: cattle shouldn’t be eating grain, they're evolved to eat grass.” Michael Pollan, in FR ES H . By keeping animals concentrated on feedlots and feeding them only grains, our current food supply system is depleting our environment. Sustainable agriculture, in contrast, benefits the environment in a myriad of ways. Preventing the contamination of our water resources from pesticides and fertilizer runoffs is one obvious way, but other benefits may be less obvious. If we returned to pasture-based cattle production, our environment would benefit from: • Us in g l es s fos sil f uel us e: On pasture, grazing animals do their own fertilizing and harvesting. It’s a different story in a confinement operation where animals are crowded into sheds or kept outdoors on barren land and all their feed is shipped to them from distant fields where crops are treated with fossil-fuel based fertilizers, sprayed with pesticides, and planted, tilled, and harvested with heavy equipment. • Cap turi n g C O 2 : Grazed pasture removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere more effectively than any land use, including forestland and ungrazed prairie, helping to slow global warming. • No need for fer tili zers or the buil dup of to xi c man ur e la goo ns: On well-managed pasture-based farms, the animals spread their manure evenly over the soil where it becomes a natural source of organic fertilizer. The manure improves the quality of the grass, which increases the rate of weight gain of the animals. It’s a closed, sustainable system. • Les s soil eros io n: Currently, the United States is losing three billion tons of nutrient-rich topsoil each year. Growing corn and soy causes six times more soil erosion than pasture. • H eal thi er so il: Grazing is better for the soil than growing grain. Six Minnesota pasturebased ranchers asked researchers to compare the health of their soil with soil from neighboring farms that produced corn, soybean, oats, or hay. At the end of four years of monitoring, researchers concluded that the carefully managed grazed land had 53% greater soil stability, 131% more earthworms, more organic matter, less nitrate pollution of groundwater and provided a better habitat for grassland birds and other wildlife. “You’ve got to understand that 70% of all the row crops in the united states … are grown for multistomached herbivores (cows), that aren’t ever supposed to eat that anyway. Only 30% goes to people, pigs and poultry. So if we went to a grass-based agriculture for our cattle, suddenly 70% of that currently assaulted land could return to a mob-stocking, herbivorous, solar-conversion, lignified, carbon-sequestration, fertilization program, and all the negatives in agriculture would come to a screeching halt.” Joel Salatin, in FR ES H. 11 E CO NO MIC B ENEFI T S “If we just had every person…spend ten dollars a week (on small, local farmers), I mean that would be such a small percentage of their overall food budget but it would make such a huge statement and have such a huge economic impact. Not only on the small family farms but to the economy, because the amount of money generated by that would be tripled or quadrupled by what it would bring back to our local economies and our rural areas, which are really dying.” Diana Endicott, in FR ES H . Eatin g l oc al s upp orts o ur lo cal f ar mers: American farmers, on average, receive only about 20 cents for every dollar we spend on food at the supermarket. The rest goes to processing, transportation, packing, and other marketing costs. In addition, these farmers, on average, get to keep only ten to fifteen cents from every dollar they earn; the rest pays for fertilizer, fuel, machinery, and other production expenses — items typically manufactured and often provided by suppliers outside of the local community. Farmers who sell food direct to local customers, on the other hand, receive the full retail value for everything they sell, a dollar for each food dollar spent. Because they contribute a larger proportion to the production process and purchase fewer commercial production inputs, they then get to keep half or more of each food dollar they earn. It’s a win-win situation: they receive a larger proportion of the total income as a return for their labor, management, and entrepreneurship. Eatin g lo cal r evi tal izes o ur lo cal eco no mi es: Supporting local farmers also means supporting our local economies. Farmers who sell locally also tend to spend locally, both for their personal and farming needs, which also contribute more to the local economy. Indeed, the creation of local food network creates new jobs and new business opportunities, in order to process, warehouse, and distribute the products. Eatin g lo cal hel ps sav e far mla n d: More than one million acres of U.S. farmland are lost each year to residential and commercial development. The loss may seem small in relation to the total amount of farmland — more than 950 million acres — we do have, but an acre lost to development is an acre lost forever from food production. A NIM AL H EAL T H B ENEFI T S Animals raised on pasture enjoy a much higher quality of life than those confined within factory farms. When raised on open pasture, animals are able to move around freely and carry out their natural behaviors. This lifestyle is impossible to achieve on industrial farms, where thousands of animals are crowded into confined facilities, often without access to fresh air or sunlight. These stressful conditions are a breeding ground for bacteria and the animals frequently become ill, so factory farms must routinely treat them with antibiotics to prevent outbreaks of disease. 12 B IO S Abo ut the f il mmak er Ana Jo an es — producer and director of FR ES H, is a Swiss-born documentary filmmaker whose work addresses pressing social issues through character-driven narratives. After traveling internationally to study the environmental and cultural impacts of globalization, she graduated from Columbia Law School in May 2000, awarded as a Stone Scholar and Human Rights Fellow. Thereafter, Ana created Reel Youth, a video production program for youth coming out of detention. In 2003, Ana and her friend Andrew Unger produced Generation Meds, a documentary exploring our fears and misgivings about mental illness and medication. FR ES H is Ana’s second feature documentary. Abo ut the p ar ti cip an ts f ea tured i n FRE S H: Will Al len — 6’ 7” former professional basketball player Will Allen is now one of the most influential leaders of the food security and urban farming movement. His farm and not-for-profit organization, Growing Power, has trained and inspired people in every corner of the U.S. to start growing food sustainably. This man and his organization go beyond growing food. They provide a platform for people to share knowledge and form relationships in order to develop alternatives to the industrial food system. Dav i d Bal l — Supermarket owner and innovator, David Ball is the founder of Good Natured Family Farms, an alliance of 75 family farms surrounding the Kansas City metro area. They sell everything from locally produced honey to angus beef to locally owned and operated independent supermarkets, challenging our Wal-Mart-dominated economy. With the rise of big chain stores, David Ball saw his family-run supermarket dying, along with a oncethriving local farm community. He reinvented his business, partnering with area farmers to sell locally grown food and specialty food products at an affordable price. His plan has brought the local economy back to life. John Ik er d — raised on a small dairy farm in southwest Missouri, Ikerd received his BS, MS, and Ph.D. degrees in agricultural economics from the University of Missouri. He worked in private industry for a time and spent thirty years in various professorial positions at North Carolina State University, Oklahoma State University, University of Georgia, and the University of Missouri before retiring in early 2000. Since retiring, he spends most of his time writing and speaking on issues related to sustainability with an emphasis on economics and agriculture. Ikerd is author of Sustainable Capitalism, A Return to Common Sense, Small Farms are Real Farms, and Crisis and Opportunity: Sustainability in American Agriculture. “We can tip the balance of nature to a certain extent, but when we try to tip it too far it creates problems.” – John Ikerd 13 An drew K i mbr ell — Kimbrell is a public interest attorney, activist and author. He has been involved in public interest legal activity in numerous areas of technology, human health and the environment. After working for eight years as the Policy Director at the Foundation for Economic Trends, Kimbrell established the International Center for Technology Assessment (CTA) in 1994 and the Center for Food Safety (CFS) in 1997. Kimbrell has written several books and given numerous public lectures on a variety of issues. He has been featured on radio and television programs across the country, including The Today Show, the CBS Morning Show, Crossfire, Headlines on Trial, and Good Morning America. He has lectured at dozens of universities throughout the country and has testified before congressional and regulatory hearings. In 1994, the Utne Reader named Kimbrell as one of the world’s leading 100 visionaries. “Medium sized organic is far more productive than industrial-sized agriculture.” – Andrew Kimbrell Russ Kremer — 15 years ago, Russ Kremer ran an industrial hog confinement operation in Frankenstein, Missouri. Following standard practices, he fed his pigs daily doses of antibiotic for growth efficiency and to ward off illnesses. Then, one day Russ was gored by one of his hogs and nearly died from an antibiotic-resistant infection. He realized the danger posed by the overuse of antibiotics, and immediately transformed his farm. Today his hogs are antibiotic-free. Russ is the founder of the Ozark Mountain Pork Coop and the president of the Missouri Farmers Union. Mic ha el Poll an — Michael Pollan is the author, most recently, of In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto. His previous book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals, was named one of the ten best books of 2006 by the New York Times and the Washington Post. He is also the author of The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World, A Place of My Own, and Second Nature. A contributing writer to the New York Times Magazine, Pollan is the recipient of numerous journalistic awards, including the James Beard Award for best magazine series in 2003 and the Reuters-I.U.C.N. 2000 Global Award for Environmental Journalism. Pollan served for many years as executive editor of Harper’s Magazine and is now the Knight Professor of Science and Environmental Journalism at UC Berkeley. Joel Sala tin — world-famous sustainable farmer and entrepreneur, Joe Salatin and his farming methods are hailed by Michael Pollan (also featured in FRE S H), author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Joel Salatin writes in his website that he is “in the redemption business: healing the land, healing the food, healing the economy, and healing the culture.” By closely observing nature, Joel created a rotational grazing system that not only allows the land to heal but also allows the animals to behave the way the were meant to — as in expressing their “chicken-ness” or “pig-ness”, as Joel would say. “Let’s treat the herbivore like an herbivore first and then the other things will fall into place.” – Joel Salatin 14 C REDITS Prod uc ed & Dire cte d b y ana Sofia joanes Edited b y Mona Davis Additiona l E diting b y Jeremiah Zagar Dir ector of P hotog raph y Valery “Lali” Lyman Additiona l Ca mera Work b y Michael Fox, Dena Aronson, Jeremiah Zagar, Andrea Nielson & ana Sofia joanes Mu sic b y David Majzlin Per form ed b y Violin Annaliesa Place Violin Brittany Boulding Viola Natasha Lipkina Cello Sophie Shao Progr ammi ng, pia no, g uitar David Majzlin Mixed by David Majzlin Recor d ed at Germano Studios, NYC Soun d re- Recor din g Mix er Tom Paul Soun d D esi gn er Eric Milano Soun d Faci lity Gigantic Studios Digital I nter me diate Facilit y Final Frame Digital I nter me diate Colorist Stewart Griffin 15 Digital I nter me diate Editor Joseph Lee Digital I nter me diate Prod uc er Kristen Molina Animation b y: Yussef Cole Poster D esig n b y: Tom Seltzer Distribution & Out rea c h by: Lisa Madison Post Prod uction Assista nts Andrea Nielsen Frederik Boll Saralena Weinfield Arc hival Foota g e Mosaic Films / King Corn Ivan Bridgewater Buffalo Field Campaign Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc. (http://www.denniskunkel.com/) Miranda Productions, Inc. Pesticide Education Center The Humane Farming Association Beyond The Frame BBC Thought Equity FRAME POOL ABC News Fun din g & S upport b y Gigantic Studios The Jerome Foundation NYSCA (logo at http://nysca.org/public/grants/when_you_get.htm) Yelp.com (logo attached) Pam and Bill Michaelcheck & Ari Barkan Aaron Cohen Dahli Coles Frances Cassidy Paul Waimberg Randolph Quinby Charles Ewald Elaine Brumberg Rosemary Pritzker Mark Giesecke Fisca l Sponsor IFP 16