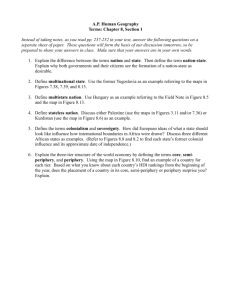

Politics, Identity, Territory. The “Strength” and “Value” of Nation

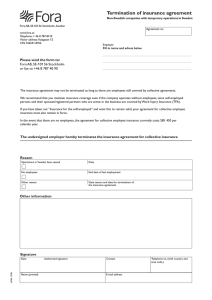

advertisement