Legal but Unethical: Interrogation and Military

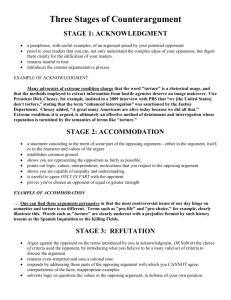

advertisement