Master's Thesis

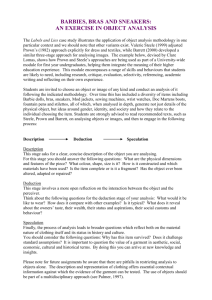

advertisement