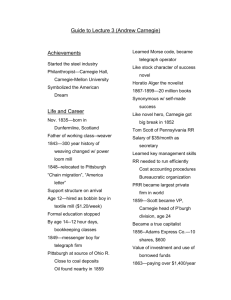

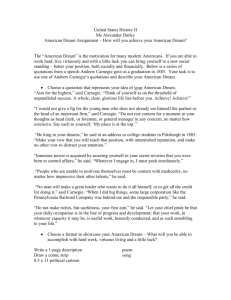

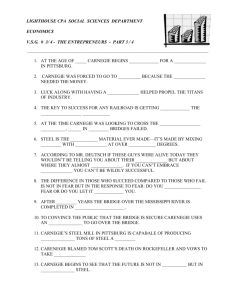

Plutocratic Leadership - Microelectronics Research and

advertisement