BCCC-large report - The Abell Foundation

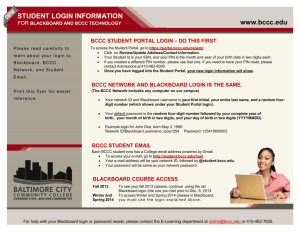

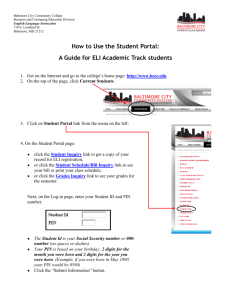

advertisement