Read more…

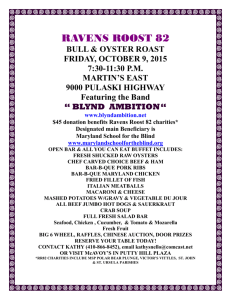

advertisement

CURRENT INTELLIGENCE Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 2015, Vol. 10, No. 7 Celebrities like Rihanna, who have a successful history of endorsing products, may be more likely to achieve this. The Court of Appeal reiterated that there is (still) no ‘image’ right on which celebrities can rely. The UK might be said to have a narrow approach to the ability to protect the use of their image. By requiring celebrities to prove a misrepresentation, third parties have quite extensive leeway. There is therefore a degree of irony in the practical significance of the decision; despite Rihanna prevailing against Topshop on this occasion, the judgment demonstrates how difficult it will be for other celebrities to bring similar claims in the future. For now, at least, celebrities accustomed to USA-style protection of their ‘personality’ or ‘image’ right will continue to face far greater hurdles in the UK. tion (2014 FC 1237 at para 51 (discussing subsection 37(1) of the Act)). It is only after advertisement, and during the opposition stage, that non-distinctiveness may be raised under subsection 38(1)(d). ‘FLIP-TOP’ is a commonly used word in the tobacco industry and ‘is a defined word that refers to a container that has a lid that is easily flipped open’. By definition then, as a proposed mark the term lacked the requisite distinctiveness for the public to necessarily associate it with Philip Morris’s products. Although descriptiveness is related to distinctiveness, the two concepts were explicitly distinguished by the Court. At para 81 Justice Bédard emphasized that her analysis was confined to that of distinctiveness only: 500 Jeremy Blum and Sean Ibbetson Bristows LLP Emails: jeremy.blum@bristows.com and sean.ibbetson@bristows.com doi:10.1093/jiplp/jpv061 Advance Access Publication 22 April 2015 Practical significance Copyright FLIP-TOP not distinctive of Philip Morris, rules Federal Court of Canada B Philip Morris Products SA v Imperial Tobacco Canada Ltd, 2014 FC 1237, Federal Court of Canada, 18 December 2014 The Federal Court of Canada held that the term ‘FLIPTOP’ was not distinctive of Philip Morris as it described a type of packaging and was not necessarily indicative of source. Legal context Section 38 of Canada’s Trade-mark Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. T13 sets out the grounds on which a proposed mark may be opposed. Subsection 38(2)(d) provides that a mark may be opposed where it is ‘not distinctive’. Facts Philip Morris applied to register ‘FLIP-TOP’ as a trade mark for tobacco and a variety of tobacco products. This mark had not yet been used and the Trade-marks Opposition Board found that it lacked distinctiveness because it described a type of packaging commonly used for tobacco products. Philip Morris appealed the decision. Analysis A trade mark’s lack of distinctiveness is not one of the grounds under which the Registrar may refuse an applica- Source identification is the main purpose of a trade mark. Proposed marks that are themselves a common term will necessarily lack the requisite distinctiveness for registrability. Allowing such marks to acquire distinctiveness, and a secondary meaning, through concerted marketing efforts and actual use, may have been the wiser course of action in this case, instead of having the mark snuffed out at first instance. Emir Crowne Associate Professor, University of Windsor, Faculty of Law Email: emir@uwindsor.ca Adrian Werkowski Law Student (LAW III), University of Windsor, Faculty of Law doi:10.1093/jiplp/jpv072 Advance Access Publication 18 April 2015 Fresh Trading held to be equitable owner of Innocent Smoothies’ ‘the Dude’ copyright B Fresh Trading Limited v Deepend Fresh Recovery Limited and Andrew Thomas Robert Chappell [2015] EWHC 52 (Ch), High Court, England and Wales, 26 January 2015 A court ruled that Fresh Trading (the owner of the Innocent Smoothies brand of soft drinks) is the equitable owner of the copyright in ‘the Dude’ logo, despite the fact that it did not pay for it. Downloaded from http://jiplp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on June 22, 2015 I do not find it necessary to determine whether the term ‘fliptop’ is descriptive of an intrinsic quality of the wares themselves such as a feature, trait or characteristic. In the present context, the key consideration is not whether the mark describes an aspect of the product that is necessarily ‘intrinsic’, but whether the term is capable of identifying the source of the wares in light of the overall product and market. CURRENT INTELLIGENCE Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 2015, Vol. 10, No. 7 Legal context The court considered issues of contractual construction, ownership and assignment of copyright under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (‘CDPA’), sections 90 and 91, and whether acquiescence, proprietary estoppel and/or laches prevented the copyright owner from asserting infringement of its rights. Facts Lockton (CEO of old Deepend) as more or less equal shareholders. In April 2009 Deepend had applied to the Office for Harmonisation of the Internal Market (OHIM) to cancel Fresh’s two Community trade marks of the Dude, and succeeded in November 2012. Fresh appealed that decision and in July 2013 filed a claim in the High Court, seeking primarily a declaration that Fresh was the owner of the copyright. Deepend counterclaimed for a declaration that it was the owner and for copyright infringement. There was a dispute between the parties as to whether the original agreement between Fresh and old Deepend was signed, the only evidence of the arrangement existing in an unsigned ‘Heads of Agreement’ document, expressly marked ‘subject to contract’. Neither party was able to find any signed original or copy. Analysis The simple action for damages for breach of contract or specific performance of the obligation to allot shares was time-barred by the time new Deepend became involved. That left only the copyright to enforce as the sole means of obtaining recompense. No legal assignment of copyright under s.90 (assignment of copyright) or s.91 (assignment of future copyright) CDPA The contract (not drafted by lawyers) set out the scope of each party’s obligations. The parties agreed to work cooperatively and collaboratively. Clause 4 set out the value, method of determination and nature of the remuneration (in shares not cash, and in three tranches throughout the project’s lifetime) and clause 5 dealt with the ownership of IP. It read: Fresh Trading Ltd receive full intellectual copyright of any work, creative ideas or otherwise presented by the agency and then subsequently approved by Fresh. Work not approved by Fresh remains under the ownership of Deep End. There was no dispute that Fresh went on to approve the Dude logo after it was designed in early 1999 and much of the other work done by Deepend. However, Fresh gave Deepend neither its shareholding in the business (as outlined in the contract) nor any other kind of recompense before Deepend went into liquidation in 2001. Before the company was dissolved, Andrew Chappell bought the copyrights in the Fresh work from the liquidator in 2007. Mr Chappell was a good friend of Mr Streek, and wanted to help prevent a perceived injustice. Mr Chappell then assigned the rights to a newly formed Deepend (the first defendant) in 2009, with himself, Mr Streek and Gary In the High Court, Deputy High Court Judge Robert Englehart QC found that, while there was insufficient evidence to justify a finding that the parties had signed anything, they were acting in accordance with the unsigned Heads of Agreement, despite the use of the words ‘subject to contract’. He was clearly right to do so. That was important because, without the signed document, the judge was unable to find that the legal title had passed to Fresh under s.90 CDPA, which requires an assignment of copyright to be signed by the assignor. Fresh sought to argue that the unsigned Heads could act as an assignment of future copyright (under s.91 CDPA) but the judge disagreed, agreeing with Deepend that s.91 could not cover an assignment of rights that only came into existence on the fulfilment of a subsequent condition. In this case, that condition was that the work had to be approved by Fresh. Equitable assignment found despite non-payment However, the judge did find that there was, in his view, an equitable assignment of copyright, based on his construction of the contract. He decided that the share allotment provisions and the IP assignment clause were separate obligations, not conditional, one upon the other. The consideration for the IP assignment was, according to the judge, the promise to allot shares rather than the actual allotment, so there was no ‘failure of consideration’. Downloaded from http://jiplp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on June 22, 2015 In 1998 Fresh Trading, then a start-up smoothie business, sought a design agency to undertake its design work in return for shares. Fresh was put in touch with a then leading design agency, Deepend. Deepend enthusiastically agreed to the arrangement and worked on designing prototype bottles, the logo, labelling and website for the product. Deepend’s work amounted to thousands of hours. In 1999, David Streek, lead designer at Deepend, created a logo known as ‘the Dude’ (a face with a halo), which has been the face of Innocent Smoothies for more than 15 years, and has been used on more than 500 million bottles: 501 502 CURRENT INTELLIGENCE Did the judge need to conclude as he did? project and forgetting the administrative formalities in the process. This is admittedly easier said than done. For designers and design agencies in particular, it is evident from this case that contracts should make it expressly and unambiguously clear that the transfer of IP is conditional on payment being made, and deal with the situation where payment is not made but the works are used for an extended period (ie a bare and revocable licence is all that is granted). It also provides a prompt for agencies to check their standard terms and conditions and ensure that there is no doubt as to their effect. Richard Kempner and Jake Campbell (acted for the defendants in this litigation) Kempner and Partners LLP Emails: kempner@kempnerandpartners.com; campbell@kempnerandpartners.com doi:10.1093/jiplp/jpv066 Advance Access Publication 9 April 2015 SPCs An innovative decision on supplementary protection certificates for combination products? B Actavis Group PTC EHF & Actavis UK Ltd v Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co KG, Case C-577/13, Court of Justice of the European Union, ECLI:EU:C:2015:165, 15 March 2015 The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) refuses a supplementary protection certificate (SPC) for a combination product comprising of a known and innovative ingredient, where the innovative ingredient already had the benefit of an SPC. Acquiescence, estoppel and/or laches The judge did not decide (because he did not have to) but opined that had it been necessary for him to do so, then his inclination would have been that Deepend was barred from asserting its copyright by reason of acquiescence, estoppel and/or laches. Yet even that inclination is open to doubt. It is hard to see that there were any acts or omissions by Deepend (old or new) relied upon by Fresh, which were sufficient to justify such a finding (tentative though it was). Practical significance With the continuing trend of start-ups, with potentially valuable IP, appearing every day, this case is a reminder of the benefits of clearly delineating IP ownership at an early stage and for the parties not to get carried away with a Legal context The process of bringing new medicines to market is long and arduous. During this process, the duration of the originator’s patent protection is eroded. In recognition of this, and to provide an incentive to develop and bring new products to market, pharmaceutical patents can be extended for a period of up to five years, if the criteria in Regulation 469/2009 are met, resulting in the grant of a supplementary protection certificate (SPC). It follows that not every new product will obtain an SPC. Given the commercial importance of SPCs that protect product monopolies at the height of their commercial success, they have been subject to considerable judicial scrutiny by both national courts and the CJEU. Despite this, the SPC jurisprudence is still evolving, and there remain many areas of uncertainty requiring clarification. Downloaded from http://jiplp.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on June 22, 2015 What sets this case apart from other cases in this area is that the payment was never made (eg Griggs Group v Evans [2005] EWCA Civ 11 where the designer was paid). In the authors’ opinion, the equitable maxim ‘he who comes to equity must do equity’ (eg Coatsworth v Johnson (1886) 54 LT 520) appears to have been ignored by the judge. It is the authors’ view that he should have concluded that it was inequitable to grant title to Fresh without Fresh complying with its part of the bargain by compensating Deepend for the work it did to develop the copyright material. Assignment on the basis of a mere agreement to do so should not have been enough. The effect of the decision is that it allowed Fresh to obtain the full benefit of the agreement (assignment of copyright) without having to allot and issue the agreed shareholding. The judge’s interpretation of the parties’ agreement, requiring Deepend unconditionally to assign the copyright without any compensation, imposed upon Deepend all the detriment of the agreement without conferring upon it any benefit and, in particular, without any requirement that Fresh in fact provide the agreed consideration for the work done. The judge was clearly concerned about the potential effect on Fresh’s business if he had found that Deepend had owned the copyright (in law and equity) and that all Fresh had was a terminable licence. But to deal with that concern, it was open to him to have found that Deepend did in fact own the copyright, but nonetheless to refuse to grant Deepend the discretionary remedy of an injunction. That would have left Deepend in the position that its sole remedy was damages, to be assessed if not agreed. And, if that had happened, what better measure of the damages payable would there have been, than the value of the shares (at an appropriate exit point) that Deepend were meant to have been paid? Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 2015, Vol. 10, No. 7