Political Parties in Post-Suharto Indonesia

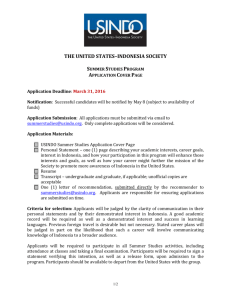

advertisement