Southern Ballads and Medieval Roots

advertisement

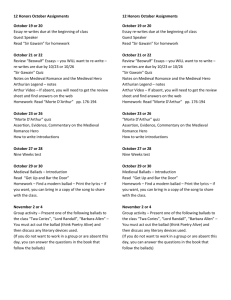

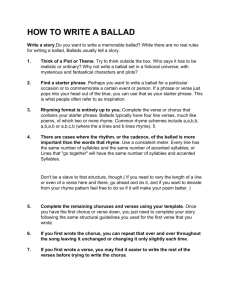

Southern Ballads and Medieval Roots Heather Jennings English 221 Dr. Capps 3/22/07 First of all, what exactly determines a traditional folk ballad? According to W. K. McNeil and his collection of Southern Folk Ballads, folk ballads should be classified as “[...] folksongs that tell a story while folksong is reserved for those numbers that do not contain a narrative (McNeil 10). In other words, folk ballads are songs that carry on a story, primarily through repetition. Many children hear at least pieces of traditional ballads through nursery rhymes, although of course they do not yet grasp the cultural or historical significance from which many of these rhymes originate. For instance, many scholars believe that “Little Jack Horner” was based originally on an orphan rewarded not just with a plum, but with a deed to church property after King Henry VIII had contrived the death of the abbot (who had raised the orphan) as a way to close the monastery of Glastonbury (Brand 23). There are several of these examples, including the well-known social and political satire of “Humpty Dumpty” and his great fall (25). Yet at the risk of digressing from the point, perhaps a ballad’s significance is not based on its original meanings as much as the active expression of it. For instance, Evelyn K. Wells claims in her study of folklore and ballads that “[t]he full effect of folk poetry and folk music is not to be derived from one hearing; it is felt only by repetition.” (Wells 91). McNeil furthers this with his point that “[ballads] do not exist by themselves but are, rather, kept alive by various singers.” (McNeil 24). Therefore, because the stories involved are continually maintained through oral tradition, most of the stories are naturally embellished or modified to some degree or another. This is not to say that the original meaning of these stories are not significant or should be overlooked. Indeed, most ballad narratives are simple enough that the main event seems to hold over time. According to Wells, romantic and historical ballads with the longest “life-span” stick to an effectively simple story to remain “[...] unmuddied by trivial matter.” (Wells 77). This makes perfect sense, especially regarding those like the Robin Hood Ballads, which she mentions here and are believed to date back to around 1388. Wells also points out that many writers of today’s ballads are less smooth in practicing “simplicity of language” and the “objectivity” that seem to have come more naturally to poets of the more traditional ballads (325). Most of today’s writing and even speaking contains more detail and certainly more figurative inference. Although many ballads are in the romantic category, written and spoken ballads as a whole are simple and completely literal in meaning. In the ballad “The Two Sisters,” for instance, the primary device in the story is simply the repetition, of actions and of objects. The young man “a-courting” the youngest sister gives her a “gay gold ring” and then a beaver hat, after which the oldest sister pushes her into the sea, whereupon she swims to end up at the miller’s pond (McNeil 150-53). Going back to Wells’ point on the ballad’s full effect, this condensed description takes away any significance that would typically be portrayed through the singer of the ballad, such as the repetition and rhythm, and perhaps the story’s tone as well. This seems to be a very popular ballad, apparently derived from an old English ballad referred to as “The Twa Sisters.” (Wells 161). Yet as there are so many others, the reference here is mainly an arbitrary example. So who exactly generates and sings these ballads? Of course, the answer is a broad one; the sources for folk ballads, as well as medieval ballads, include just about every type of person. As McNeil mentions, there is a common generalization regarding the source of these ballads, especially within the Southern Appalachians; many assume that these folksingers are “rustic, unschooled illiterate(s),” isolated from most civilization (24-25). Oscar Brand also mentions this common assumption in his research as the “early hypothesis” of folk music (Brand 5). To an extent, it is probably true. The oral exchange of verse originally comes from many in the Middle Ages who were illiterate and thus used repetition as a means of memorization. However, research from both sources indicates many traditional folk ballad singers and creators in Tennessee that were found to be highly educated, among them professors and doctors. As far as older sources for ballads, many that are now sung by peasants or everyday folk are found to be of aristocratic medieval origin simply through the subject of the ballad (Wells 194). An example given here is “The Wife of Usher’s Well.” As the song explains that the “lady gay” sent her children “[t]o learn their grammars three,” it makes sense that the subject must have been of a higher socio-economic class of the medieval period (Wells 155). According to Wells, ballads mainly originate from four sources: the “rhythmic refrain” of the dance, individual poets, “the courtly poets, often minstrels” of the medieval period, and the monks (193). The earliest text of the ballad form, referred to as the “Judas text,” dates back before 1300 (193). However, due to the nature of the ballad’s continual variation, many scholars have gone through much debate over the authentic sources of most ballads. In Southern Music; American Music, author Bill Malone also mentions the question of ballad origins, in that “[n]o problem of folk scholarship has been more hotly debated...” (11). “House Carpenter” is another example of a well-known ballad whose specific origin is unknown. Said to be an “ancient British ballad,” its common theme of tragedy and loss has carried it through several centuries; yet a more specific source seems impossible to find (Alarik). Nevertheless, the sad but classic story continues to be spread through contemporary artists and singers. Research has indicated, however, older versions of the story that have apparently been changed or glossed over, throughout time. For example, in certain versions of “The House Carpenter” or “The House Carpenter’s Wife,” the man who takes a woman away from her baby (and her husband) is not just a sailor, whom she curses in the end, but is actually the Devil (McNeil 18). Yet whoever the original poet or singer, the story serves as only one of the many examples of poetic narratives that have carried on, been enhanced and kept alive over the centuries. It is really quite incredible to ascertain that some versions of many of today’s poetic ballads, now written as well as sung, have stemmed from tales that originated back around Chaucer’s day. Works Cited Alarik, Scott. “A Maniac for Folk: Natalie Merchant Goes Trad.” Sing Out!, 47.3 (fall 2003): 35-39. <http://0-galenet.galegroup.com.library.acaweb.org> (20 March 2007). Brand, Oscar. The Ballad Mongers: Rise of the Modern Folk Song. Toronto: Fitzhenry and Whiteside Limited, 1967. Malone, Bill C. Southern Music; American Music. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1979. McNeil, W. K. American Folklore Series: Southern Folk Ballads, Volume II. Little Rock: August House, Inc., 1988. Wells, Evelyn Kendrick. The Ballad Tree. New York: The Ronald Press Company, 1950.