A simple definition of culture: Learned and shared patterns of

advertisement

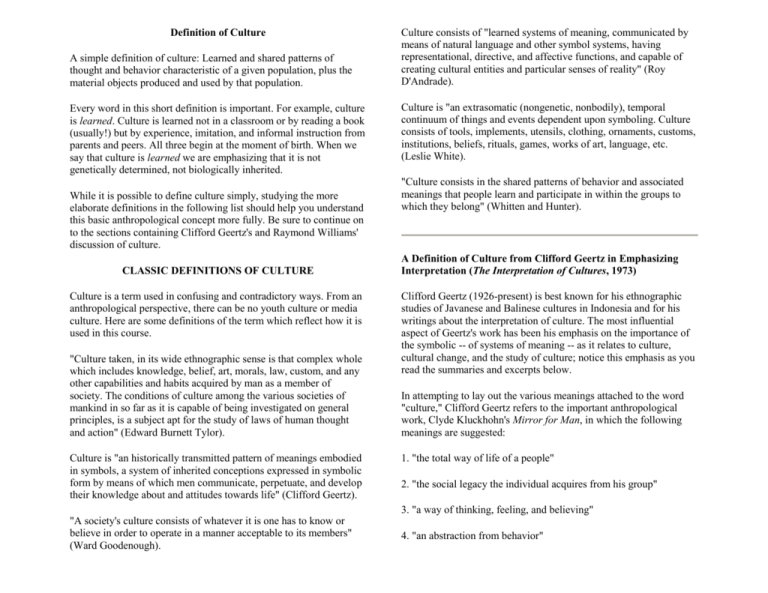

Definition of Culture A simple definition of culture: Learned and shared patterns of thought and behavior characteristic of a given population, plus the material objects produced and used by that population. Every word in this short definition is important. For example, culture is learned. Culture is learned not in a classroom or by reading a book (usually!) but by experience, imitation, and informal instruction from parents and peers. All three begin at the moment of birth. When we say that culture is learned we are emphasizing that it is not genetically determined, not biologically inherited. While it is possible to define culture simply, studying the more elaborate definitions in the following list should help you understand this basic anthropological concept more fully. Be sure to continue on to the sections containing Clifford Geertz's and Raymond Williams' discussion of culture. CLASSIC DEFINITIONS OF CULTURE Culture is a term used in confusing and contradictory ways. From an anthropological perspective, there can be no youth culture or media culture. Here are some definitions of the term which reflect how it is used in this course. "Culture taken, in its wide ethnographic sense is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society. The conditions of culture among the various societies of mankind in so far as it is capable of being investigated on general principles, is a subject apt for the study of laws of human thought and action" (Edward Burnett Tylor). Culture is "an historically transmitted pattern of meanings embodied in symbols, a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic form by means of which men communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge about and attitudes towards life" (Clifford Geertz). Culture consists of "learned systems of meaning, communicated by means of natural language and other symbol systems, having representational, directive, and affective functions, and capable of creating cultural entities and particular senses of reality" (Roy D'Andrade). Culture is "an extrasomatic (nongenetic, nonbodily), temporal continuum of things and events dependent upon symboling. Culture consists of tools, implements, utensils, clothing, ornaments, customs, institutions, beliefs, rituals, games, works of art, language, etc. (Leslie White). "Culture consists in the shared patterns of behavior and associated meanings that people learn and participate in within the groups to which they belong" (Whitten and Hunter). A Definition of Culture from Clifford Geertz in Emphasizing Interpretation (The Interpretation of Cultures, 1973) Clifford Geertz (1926-present) is best known for his ethnographic studies of Javanese and Balinese cultures in Indonesia and for his writings about the interpretation of culture. The most influential aspect of Geertz's work has been his emphasis on the importance of the symbolic -- of systems of meaning -- as it relates to culture, cultural change, and the study of culture; notice this emphasis as you read the summaries and excerpts below. In attempting to lay out the various meanings attached to the word "culture," Clifford Geertz refers to the important anthropological work, Clyde Kluckhohn's Mirror for Man, in which the following meanings are suggested: 1. "the total way of life of a people" 2. "the social legacy the individual acquires from his group" 3. "a way of thinking, feeling, and believing" "A society's culture consists of whatever it is one has to know or believe in order to operate in a manner acceptable to its members" (Ward Goodenough). 4. "an abstraction from behavior" 5. " a theory on the part of the anthropologist about the way in which a group of people in fact behave"" 6. a "storehouse of pooled learning" 7. "a set of standardized orientations to recurrent problems" imaginative universe within which their acts are signs" (Geertz pp. 12-13). Culture is Ordinary Raymond Williams, Moving from High Culture to Ordinary Culture Originally published in N. McKenzie (ed.), Convictions, 1958 8. "learned behavior" 9. a mechanism for the normative regulation of behavior 10. "a set of techniques for adjusting both to the external environment and to other men" 11. "a precipitate of history" 12. a behavioral map, sieve, or matrix "The concept of culture I espouse. . . is essentially a semiotic one. Believing, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretative one in search of meaning. It is explication I am after. . . . (Geertz pp. 4-5)" Geertz compares the methods of an anthropologist analyzing culture to those of a literary critic analyzing a text: "sorting out the structures of signification. . . and determining their social ground and import. . . . Doing ethnography is like trying to read (in the sense of 'construct a reading of') a manuscript. . . ." Once human behavior is seen as . . . symbolic action--action which, like phonation in speech, pigment in painting, line in writing, or sonance in music, signifies--the question as to whether culture is patterned conduct or a frame of mind, or even the two somehow mixed together, loses sense. The thing to ask [of actions] is what their import is" (Geertz pp. 9-10). Geertz argues that culture is "public because meaning is"--systems of meaning are necessarily the collective property of a group. When we say we do not understand the actions of people from a culture other than our own, we are acknowledging our "lack of familiarity with the "Culture is ordinary: that is the first fact. Every human society has its own shape, its own purposes, its own meanings. Every human society expresses these, in institutions, and in arts and learning. The making of a society is the finding of common meanings and directions, and its growth is an active debate and amendment under the pressures of experience, contact, and discovery, writing themselves into the land. The growing society is there, yet it is also made and remade in every individual mind. The making of a mind is, first, the slow learning of shapes, purposes, and meanings, so that work, observation and communication are possible. Then, second, but equal in importance, is the testing of these in experience, the making of new observations, comparisons, and meanings. A culture has two aspects: the known meanings and directions, which its members are trained to; the new observations and meanings, which are offered and tested. These are the ordinary processes of human societies and human minds, and we see through them the nature of a culture: that it is always both traditional and creative; that it is both the most ordinary common meanings and the finest individual meanings. We use the word culture in these two senses: to mean a whole way of life--the common meanings; to mean the arts and learning--the special processes of discovery and creative effort. Some writers reserve the word for one or other of these senses; I insist on both, and on the significance of their conjunction. The questions I ask about our culture are questions about deep personal meanings. Culture is ordinary, in every society and in every mind.

![Word Study [1 class hour]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007905774_2-53b71d303720cf6608aea934a43e9f05-300x300.png)