EGS Case Study - Malaysia _Final Report.doc

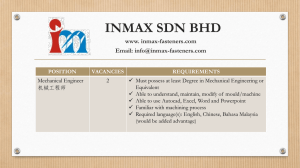

advertisement