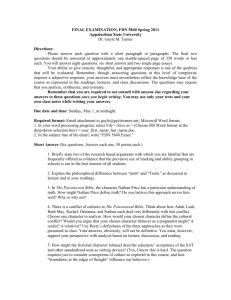

Green_Chapter 4_Choo.. - Society for the Advancement of American

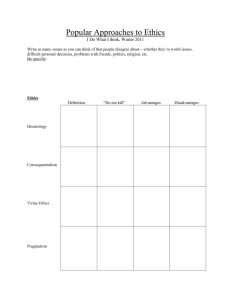

advertisement