Face Value? Customer views of appropriate formats for embodied

advertisement

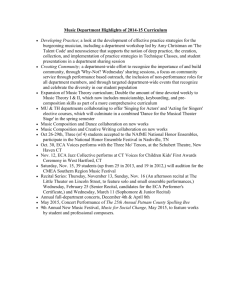

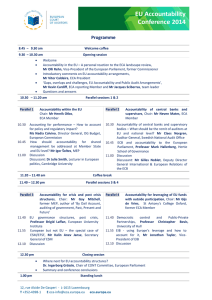

Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 Face Value? Customer views of appropriate formats for embodied conversational agents (ECAs) in online retailing Kathy Keeling Manchester School of Management, UMIST, UK kathy.keeling@umist.ac.uk Susan Beatty Manchester School of Management, UMIST, UK s.beatty@umist.ac.uk Peter McGoldrick Manchester School of Management, UMIST, UK peter.mcgoldrick@umist.ac.uk Linda Macaulay Department of Computation UMIST, UK lindam@co.umist.ac.uk Abstract Although the motivational benefits of Embodied Conversational Agents in other areas have been demonstrated their potential for relationship building within e-tailing has been little utilized. In this exploratory paper we consider customer perceptions of what types of ECA are appropriate to retailing websites using data from semi-structured interviews with 30 Internet shoppers. Extrapolating the findings from the advertising literature concerning match-up between endorser and brand, product or retailer we find this will be an important element in the acceptability and viability of ECAs on retail websites. It is apparent that great care has to be taken in matching not only the physical characteristics of the ECA to perceptions of the brand, product or retailer but also to the goals and motivations of potential customers of a website. We also find that introducing customer interaction into the ‘match-up’ mix introduces a new level of complexity, that of matching customer expectations. It is this level of service that may be most difficult for technology and organizations to meet. 1. Introduction The consequences of the experience of using computers and associated software go beyond the objective outcomes of task fulfillment. A recent research focus has been on the influence of computers as ‘social actors’. Users seem to respond to computers as social actors when computer technologies adopt animate characteristics, play animate roles, or follow social rules or dynamics (25). For online retailing, the projection of a believable, engaging, synthetic salesperson or salescharacter on computer screens through an embodied conversational agent (ECA) for the engagement of human users in communication interaction is of particular interest. Such ECAs would appear on the screen and “exhibit … life-like behaviors, such as speech, emotions, gestures and eye, head and body movements” (8). They would work cooperatively with human users to initiate communication, monitor events and perform tasks (8). In order to answer questions or do other tasks for a prospective customer, an ECA on a retailing website must be able to carry out a twoway communication to find out what the prospective customer needs and wants. An ECA would, therefore, appear to act as a virtual sales assistant and become involved with the customer in a co-operative exchange (11). The collaborative nature of the human-agent interaction increases the likelihood of anthropomorphism (9) since the agent will appear to be capable of goal-directed, purposive and motivated communication behavior, i.e., highly social. The approximation to human discourse is inclined to elicit social responses. Thus, for some researchers this generates the possibilities that humans will react to these interactions as they would to ‘real’ interactions. 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 1 Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 2. Background Agents are already designed to be communication partners with human users and there is a body of work on the role and effectiveness of ECAs. Research has also been initiated on the impact of interaction with computers and on-screen characters (24; 19; 5). However, there still is some controversy (8) and inconsistent results about the efficacy of animated agents in user interfaces, e.g., one study of a system with an animated agent found it was rated more positively on likeability compared to a system without an animated agent (18) whereas another study found the reverse (28). Moreover, for e-retailing there is a question whether relationship building through synthetic characters is an appropriate strategy. Do customers using online retail sites desire the help or even the presence of such ECAs? Given the diversity of customers, products and salespersons what is an appropriate format and appearance for an ECA on a retailing site? Are there likely to be any undesirable consequences, such as raised expectations that cannot be met or interference with product information processing? When using on-screen persona the influence of physical appearance and accompanying social attributions is introduced (7; 5; 15; 16). The representation of the on-screen character need not be either realistic or human to invoke responses and collaboration (24). Whatever the level of realism, the lifelike embedded conversational character is highly visual and so the ‘physical’ attributes should be a subject of interest. In advertising, an important consideration is the ‘consistency’ (31); ‘appropriateness’ (27), or ‘congruence’ (17) between the copy and the visual component of the communication. This is popularly termed the "match-up hypothesis" (17). The match-up hypothesis suggests that endorsers are more effective when there is a "fit" between the endorser and the endorsed product. Initially, there was a focus on the level of attractiveness of the celebrity and the perceived fit between brand and celebrity image (22). However, custom, practice and research indicate that a contingency approach should be taken. Studies of the potency of attractiveness per se have shown ambiguous results and the effectiveness of celebrities varies by product (12). The fit between the endorser and the product or brand is sometimes better when a member of staff, a real customer or even a created ‘real’ or cartoon character is used (e.g., Jolly Green Giant or Homer Simpson). This can be explained in terms of associative learning theory (29). Associative links in memory are stronger and quicker the greater the similarity between ‘concepts’ (3). Concepts are wide-ranging and can include products, brands, attitudes, people, and schema for behaviour. Thus, we can expect online shoppers to prefer on-screen characters that match their concepts about a) the brand, product or retailer associated with the website; b) sales persons and the levels of service associated with the brand, product or retailer; c) likely customers of the website. This range of people, motives and beliefs gives much scope for unintended consequences from the presence of ECAs. The presence of a visual image, especially one that moves, may lead to interference with text processing (33) and goal achievement. The learning of pictures may occur more readily than verbal counterparts, thus, it may be attended to at the expense of textual information (7). Visual memory is thought to have superior long-term capacity and deteriorate very slowly (4) and so impressions formed and attributions made from visual information may outlast textual information. Emotional reactions to the ECA could also have effects on attitudes to the brand, product or retailer. Affective reactions generated during exposure to an advertisement can outlast the cognitive representations that had originally produced them (30). Thus, longer term assessments of the brand may also be affected. Although there is some evidence that the representation of people through the presence of photographs on websites may influence user perceptions of trustworthiness (10) a note of caution has been sounded that this is not always in a positive direction (26)! Other usability factors of the website could also be casualties. Retail websites tend to hold a great deal of information in text and pictures before adding the extra content of an ECA. Longer loading times or increased perceptions of clutter are unlikely to enhance the user assessment of the website. In considering match-up, we have been extrapolating the findings from the advertising literature concerning match-up between endorser and brand. However, ECAs go further than acting as brand endorsers, they interact with the customer. Thus, customer behaviours and expectations may also be changed. The presence 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 2 Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 of a life-like character may change people’s social behavior (28) or may increase customer awareness of organizational surveillance (23) and so become more sensitive to privacy issues as has been argued in the case of loyalty cards in retailing (13). Further, interacting with an ECA not only creates social expectancies but is also likely to lead the user to expect the system to be as flexible and intelligent as a human assistant (8; 32). 3. Research questions Retail websites with ECAs are presently few and far between and despite a rich background in the study of animated interface agents, the application to e-retail has received moderate attention in the academic literature. The available literature discusses legal and ethical ‘perils’ of using life-like characters in e-commerce (14); preferences for personae with natural facial expressions, gestures and emotions (20); the importance of conveying precise and relevant information (1). Notwithstanding, there is a ‘dichotomy of opinion’ about the acceptability of ECA for e-retail (32). They also argue that the greater the realism of the character the greater the perceived expectation of intelligence. The present study is therefore inevitably exploratory in nature. A primary need in retailing is to identify correctly those elements of service that are really important to customers (21). In this paper we ask Internet shoppers for their opinions of what types of ECA are appropriate to retailing sites. Given the diversity of customers, products and salespersons, what is an appropriate format and appearance for ECAs on retailing sites? Is there any support for the match-up hypothesis? Are there likely to be any undesirable consequences, such as raised expectations that cannot be met or interference with product information processing? This will be used to inform future experimental work. 4. Method The data presented are from semi-structured interviews with Internet users who have experience of online shopping. Recruitment of participants from a limited geographical area was necessary for practical reasons, in order that participants could be interviewed face-to-face, both initially and at several later stages in the research. A convenience sample was recruited by publicising the research on a University website, where e-mails to all staff alert them to particular news items and provided the necessary link. A core of original respondents was used to ‘snowball’ a further sample to reach 30 participants and go beyond the University. All were 18 years and above (minimum age for obtaining a credit card), used the Internet for buying goods or services at least every three months, and lived or worked in Greater Manchester, UK. Recruiting participants who were experienced Internet shoppers ensured that all would have basic knowledge about the procedures involved in purchasing online and would be eligible to take part in a diary study of their Internet shopping at a later stage. Semi-structured interviews of between 45-75 minutes were conducted at the participant’s place of work or home, each participant received a gift voucher as a token of appreciation. The lack of animated and conversational onscreen salespeople or salescharacters meant that participants were unlikely to be familiar with their use. Therefore, initially, pictures of nine ECAs presently in use were shown to participants and discussed. The aim was to acquaint them with the range of ECA that could be used. After this, they selected an Internet shopping site that they used, and discussed the appropriateness of different ECAs for that site. Participants were then shown three Internet sites that display ECAs. The sites were Cross Country TravCorps with an ECA called Lucyi, GlaxoSmithKline with an ECA called Nickii, and MSNBC with an ECA called Earthdogiii. By asking respondents to suggest appropriate characters for retail websites we test whether respondents find the idea natural. By asking for opinions about suitability of specific ECAs for specific sites we can gain deeper information on what makes an ECA appropriate to a retailing site. The websites chosen for the study represent a series from realistic human to cartoon human to cartoon animal. ‘Lucy’ is a realistic human representation and responds to questions about work opportunities in the USA for health care professionals. She is dressed in green and has limited movement of her head and shoulders. ‘Nick’ provides information about products for those wishing to give up smoking on the Nicorette website. He is portrayed as a cartoon adult male human with head and shoulders visible but without movement. Earthdog responds to questions about environmental issues, and is targeted at junior school age 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 3 Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 children. It is a cartoon dog with a globe for its body and a variety of movements. Participants were invited to interact with the ECA using the dialogue box on the screen. After a short period of interaction, participants were asked whether or not they thought the ECA was appropriate on the website and to give reasons for their opinion. They were invited to suggest other websites where the ECA might be appropriate. Interviews were tape-recorded, with participant consent. Twenty-nine participants were interviewed (10 male; 19 female); the 36 - 45 age group was the largest single group, with four participants older than this and fourteen in younger agegroups. This age profile is similar to the general UK online shopper profile. Participants had a wide variety of occupations and at least two years’ experience of using the Internet, the majority (22) used it both at work and at home. 5. Results Participants were given free choice to choose one site that they used for their Internet shopping (i.e., had a personal interest in and familiarity with) and to talk about what sort of ECA would be appropriate on it. They had little difficulty in envisioning appropriate ECAs for websites. Moreover, this was spread over a wide range of types of retail website. Taking the types of site more frequently chosen, Table 1 below summarizes the participant suggestions for appropriate ECAs for book and CD, travel ticket, computer product and supermarket retail websites. The results indicate that most ECAs were suggested because they a) resembled a person found in the corresponding off-line situation, b) could be associated with the site as a whole, c) would appeal to likely users of the site, d) represented a product sold on the Internet site. Some participants also discussed how they saw the ECA operating on the site, e.g., the animated book that opened up to offer suggestions. Table 2 below summarizes participant reactions and comments about appropriateness of the three ECAs to their original websites, a site respondents were familiar with, and other websites. These ECAs represent three levels of ‘realism’; Lucy is most human-like, Nick is a cartoon human, Earthdog, with a globe for its body, is an abstract cartoon. This allowed respondents to compare characteristics suitable across different types of website. Participants were able to interact with these characters, this added a further dimension to their discussion of appropriateness. There appears to be support for the match-up hypothesis over the factors mentioned in the list above, e.g., match with off-line salesperson, likely users of the site. However, matching expectations of provision of relevant and adequate information also emerges as important. 5.1 Match between ECA and content or purpose of the website. This contains elements of (a) and (b) in the above list. In the discussion respondents introduced their expectations from off-line situations, therefore we discuss them together. When respondents perceived the website as dealing with serious or ‘professional’ content aimed at adults, e.g., smoking cessation; hi-tech computer purchase; a more serious looking and conservatively dressed character was required. Cartoon characters and casual dress were not appreciated; characters were expected to look ‘professional’ not ‘flippant’. For example, a few respondents thought Lucy inappropriate because: “She has got her hair all over and loads of makeup on and therefore doesn’t look like a health care professional, I guess.” (female, 26-35). The majority, however, thought Lucy a neutral, helpful figure that was not intrusive. The range of websites suggested as suitable for Lucy include giving professional advice and information, e.g., guidance on recruitment, law and insurance. Nick appears on the Nicorette site that gives information about smoking cessation. Nick’s casual appearance was disliked by some nonsmoking respondents, who approached the subject as very serious and ‘medical’. “… some people might be looking for more medical information and he looks a bit casual ….” (female, 36-45) However, the importance of gauging the perception of the purpose and seriousness of a website by the actual intended audience was highlighted in this case. Two respondents who 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 4 Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 Books, CDs, DVDs (n=8) Travel tickets (n=5) Computer products (n=3) Supermarkets (n=3) Table 1: Suggested ECAs for selected retail websites Suggested character Reason (if given) A sober character (human) bookshops are quiet places A human like Lucy there’s nothing odd or offensive about her, she looks like a normal person Tarzan or an owl Tarzan goes with Amazon, an owl symbolises knowledge Like Cybelle (a cyber character with a a young person’s site microphone) An animated book it could flip open and offer suggestions An animated book or CD representative of the products sold A personified bookworm with Harry Potter type glasses on A non-human (fantasy related, or easier to represent a wide variety of animal) products with something that is not human A person in train uniform or a more associated with what you get when you go comical train driver to buy tickets An airline pilot (male) A straightforward person not a particularly entertaining site A human or animal, something living Internet shopping seems impersonal A suitcase or something flying linked to travel An animated apple (respondent used Apple Mac computer) Something that would engage the techy (in recognition of the type of user) side of your brain An object, or objects, sold by the company A female in orange and navy resembling the shop assistants found offline A capable looking woman mainly female assistants are found in supermarkets A cartoon female people associate women more than men with shopping smoked both felt that there was a good match between Nick’s appearance and the information he provided. His casual appearance was thought to be compatible with the information about ways to stop smoking. They had no wish to interact with an ECA who was critical of smoking: “If it was someone who just came out and started lambasting you for smoking, I’d be out of here in seconds.” (male, 26-35). Compared to Lucy, Nick’s appearance and age caused respondents to associate him with a rather different group of products and services. His casualness was thought appropriate for sites selling toys for people with small children, or associated with more casual dress, e.g., vets, zoos, or DIY and gardening websites. He was also thought ‘techie looking’, so could be on sites selling ‘computer packages’ and gadgets. Sites aimed at children are an exception: the comments suggest that respondents felt these need a different approach to attract children, gain their attention and not “scare them off” even on sites dealing with subjects such as the environment. Thus, twenty-five of the respondents thought Earthdog appropriate to the environment website but not serious enough for most retail sites that were not aimed at children. 5.2 Match between ECA and likely users of the site Respondents thought that part of the appropriateness of the two ‘human’ ECAs (Lucy and Nick) was that users could identify with them as being similar to them: “Well she’s probably the sort of age of somebody that would be using that site … and a lot of women are nurses …” (female, 36-45) 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 5 Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 “ I see that as what people who are quitting look like, .. if I was quitting I might want Nick to look like me.” (female, 26-35). The majority judged Lucy able to fit with most sites and likely to appeal to most age ranges. On the other hand, Nick’s appearance aroused mixed reactions and his appeal was limited. For some, his general appearance and perceived age was thought to make him look friendly, if slightly harassed, and appropriate to sites aimed at older people. However, there were also a number of comments that Nick would not match with their image of likely users of other sites, e.g., DVD and CD retailers. Those who found him inappropriate to various sites gave their reasons as “too old looking”; “he’s bald and he’s only got one eyebrow”; and “perhaps, I don’t know as though I really like him.” Earthdog was thought appropriate to sites aimed at children because of the special appeal of ‘fun’ and ‘cute’ characters for children. 5.3 Match with expectations of level of information appropriate to site. The introduction of interaction possibilities gave interesting information. Respondents were irritated by lack of knowledge or inappropriate answers to questions and this was an additional reason they thought characters inappropriate. Perceptions of lack of expected knowledge seemed to arouse particularly strong feelings: “Because he hasn’t been able to answer any of my questions I think he looks a bit stupid, but then it’s confirmed by the silly look on his face.” (female, 36-45) Participants also varied in the extent to which they regarded the ECA as presenting the information. A response to a participant’s request for information might be attributed purely to the database, or it might be attributed to the ECA. 5.4 Unexpected consequences There was mixed evidence about whether an ECA would interfere with textual processing. Self-reports on the state of attention must be considered with caution as it has been argued that they are unrelated to the actual state. Nevertheless, some respondents indicated that they were able to ignore the character if it adds little to the interaction for them and they are engaged in active processing elsewhere: “I’ve just blanked him out and concentrated on what we’re typing in and what answers are coming back again ….” (male, 36-45) “I didn’t actually look at the character, cos you’re reading the words” (male, 46-55) However, we took no measurements that might indicate the amount of interference, e.g., time on task. Secondly, the presence of another person usually enhances arousal in an individual. Thus, realistic on-screen characters may create feelings of discomfort for some individuals (8). The three characters in this study were generally thought ‘innocuous’ by most respondents. They may not engage a sufficient amount of process capacity or raise arousal to the point that there is noticeable (for the respondent) interference with text processing. However, one respondent was particularly irritated by Earthdog; its nature, he said “rubs me up the wrong way to start with”. Another comment does suggest that characters that arouse a higher degree of negative emotions might begin to interfere with processing: “… to me it’s really what’s behind that’s important. The picture itself, so long as it’s not offensive or is, I suppose, reasonably bland ….” (male, 36-45) A further consequence is raised expectations and reactions if these are not met. Some participants commented that an ECA, particularly one portrayed as a human, raised expectations that their questions would be dealt with: “My expectations should be higher because it’s being portrayed as a person so … it’s even more disappointing that their search engine is just as bad as all the others.” (male, 26-35) “No point investing all this time and money, effort and thought in producing acceptable ECAs that end up being daft, because you’re setting up an expectation that this thing can answer questions when actually it can’t ” (female, 26-35). 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 6 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE Ambivalent 2 Not appropriate 0 Earthdog Appropriate 25 Ambivalent 7 Not appropriate 8 Not appropriate 5 Ambivalent 7 Nick Appropriate 10 Does not do enough Watching words and text not character Match of globe with earth match with target audience attractive to children; humorous jolly, smiley face; prompts are good (non-smokers) Too casual and flippant not healthy –looking enough Lack of knowledge Too casual, not professional Blanked him out Fitted image of site user Cartoon would appeal to anyone Content match: Knowledgeable Smokers casual is compatible Not professional; clothes not right Not 100% relevant to task Character ineffectual Original site/ appropriateness and reasons Lucy Appropriate 18 Visual match to site: correct age, clothes, professional appearance, etc Earthdog Sales: travel holidays, pet goods, toys and games, children’s books, Services: entertainment, e-pals, thirdworld issues, geography, ecology Books CDs, DVDs Travel site; Computers Supermarkets Nick Sales DIY, gardening, ‘sites for men’, ‘Saga’ holidays, computers, electrical goods, games, toys and gadgets Services: news, tax returns, computer packages, vets, zoos and jokes DVDs and music supermarket Not relevant to the product because child orientated and not serious enough, or too specific to environmental site Attractive character for children, fit between the global body and world issues Mis-match between visual image (older, not attractive’ and product image “Would not do much for image” Casual appearance and age associated with particular markets, e.g., site for people with small children, older market Also thought ‘techie looking’ Other sites/appropriateness and reasons Lucy Sales: Travel, sportswear; clothes, shoes, Neutral, helpful figure, not intrusive. Could sell health products, supermarket, sports cars, most things; would probably fit in most places; would appeal to most age ranges books, Matches someone working in off-line situation Services: Advice, information, recruitment, business services Supermarket, airline ticket sales Not wearing uniform Computer products As long as gave up-to date information Table 2: Appropriateness of 3 chosen ECAs to original and other sites Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 7 Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 This comment and others show that poorly conceived ECAs on retail sites do not have neutral effects, rather they can raise quite strong negative emotions. Whether consciously or not, most participants saw the ECA as responsible for the information provided (or lack of it) and at least partly to blame if the response was not good. Their irritation could also be projected onto the ECA. One person said of Nick: “… if the system for answering the questions doesn’t work well... I think I would project all my irritation onto that character.” (female, 36-45) There are also dangers of the presence of the ECA being considered a sales ploy rather than to assist customers: “ … well I think they just have to actually add something to it to be worthwhile otherwise it’s just a gimmick.” (female, 36-45) 6. Discussion Real Internet shoppers find it easy to relate the idea of ECAs to particular websites. Suggestions given for suitable ECAs for sites familiar to respondents were not necessarily realistic or human-like. This supports findings from the advertising literature that people can relate to cartoon characters and these may be as powerful in affecting reactions as actual salespersons, customers or celebrities. Nevertheless, the comments on the retail sites thought appropriate for the three characters chosen suggest that more cartoon-like and ‘fun’ characters must be used with care. Although people’s reactions to ECAs differ, and likes/dislikes affect the judgment of appropriateness, there are some common factors in judging appropriateness of appearance: a) whether a character like that would be found in the corresponding off-line situation. b) whether they could be associated with the site as a whole c) who the users of the site are likely to be and their motivations and goals d) whether the appearance of the character matches the information provided e) whether the information provided matches expectations raised by the character. Respondents gave a number of examples that indicate that they expect some similarity of the character to the user of the website, at least in approach to goal attainment. Lucy was referred to as being the right gender, age and general appearance to appeal to users of the site; Nick was described as fitting the image of someone in their 40s who wanted to give up smoking. Where the ‘human’ ECA was not thought appropriate it was due to a mismatch between image held of appropriate dress and behaviour and appearance and/or mannerisms of the ECA. For example, some participants implied that Lucy’s appearance did not match the image they had of a health care professional. Ambivalence towards the ECA was explained not by inappropriateness on the site, but rather that the ECA was felt to be ineffectual. This is strong support for the ‘match-up’ hypothesis (17) and, perhaps, the associative learning explanation (29). Further, respondents overwhelmingly judged that Earthdog, the most specifically ‘matched’ character, was the most appropriate to the site, i.e., the better the match the more people will think the character appropriate. The converse also seems to apply, the more tailored to a particular site, the less likely a character is to fit with other sites, e.g., the number of types of site that Earthdog is thought appropriate for is smaller than for Lucy or Nick. Physical attractiveness, or rather lack of it, does seem to play a role, although mentioned less often for appropriateness. For most people, it seems to be one component of fit rather than the sole reason. Nevertheless, some of the comments indicate that there is a minimum level of attractiveness below which it would become more important. Interestingly, in Table 1, some choices suggest that entertainment and social motivations will also influence perceptions of appropriateness. This implies that match-up could go beyond physical appearance to the motivations for using the online shopping site. Support for this is indicated from the difference in opinions about the suitability of Nick between non-smokers and smokers. Smokers preferred a character that implied they would not be preached at, given very clinical advice or shown disapproval. Support can also be found in the suggestions for suitable ECAs that went beyond physical appearance, e.g., the book that would open to give suggestions. It is apparent that great care has to be taken in matching not only the physical characteristics of the ECA to perceptions of the brand, product or retailer but also to the goals and motivations of potential customers of a website. 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 8 Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 Match-up is also extended in another way. ECAs go further than acting as brand endorsers, they interact with the customer. The results imply there also needs to be a match-up with customer expectations for normative behaviour and levels of knowledge and help that are raised by the presence of an ECA (8; 32). Our conclusions from this exploratory research into customer attitudes to ECAs reveals that match-up will be an important element in the acceptability and viability of ECAs on retail websites. We also find that introducing customer interaction into the match-up introduces a new level of complexity, that of matching customer expectations. It is this level of service that may be most difficult for technology and organizations to meet. 6.1. Limitations and further research The scope of this study was limited to one geographical area and to people whose first language was English, or who spoke English to a high standard. With a sample size of 30, it was not feasible to compare the 28 native English speakers with the two who spoke English as a second language. Cross-cultural studies in retailing indicate variations in customer expectations of service and salesperson interaction (19). Consumer behavior research in persuasion also indicates that differences in values and attitudes result in culture-distinct associations (2) that might be reflected in ECA preference. Therefore, the conclusions, whilst supported by literature and theory, need to be tested across other cultures and languages, involving a larger number of respondents. Respondents in this study were not actually using websites with an ECA to make a purchase. Experimental studies with manipulation of level of realism, type of product and interaction style are needed to see if these exploratory results generalize to different e-retail situations and to examine the effects of ECAs on persuasion, purchasing and time taken to complete a task. 7. References [1] F. Abbattista, V. Anderson, H. H. K. Anderson, P, Lops, G, and Semeraro, “Evaluating virtual agents for e-commerce”, First International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, Bologna, Italy, (2002). Accessed online at: http://www.vhml.org/workshops/AAMAS/papers.html [2] J.L. Aaker, “Accessibility or Diagnosticity? Disentangling the Influence of Culture on Persuasion Processes and Attitudes”, Journal of Consumer Research, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, March, 26(4), (2000) pp.340-357. [3] J. R. Anderson, The Architecture of Cognition, Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA (1983). [4] S.E. Avons, and W.A. Phillips, “Visualization and memorization as a function of display time and poststimulus processing time”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 6, (1980), pp. 407-420. [5] J. Cassell, J. Sullivan, S. Prevost, and E. Churchill, Embodied Conversational Agents, MIT Press, USA, (2000). [6] S. Chaiken, “Communicator physical attractiveness and persuasion”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, (1979), pp.1387-1397. [7] T.L. Childers, and M.J. Houston, “Imagery paradigms for consumer research: alternative perspectives from cognitive psychology advances”. Consumer Research, 10, (1983), pp. 59-64. [8] D. Dehn, and S. Mulken, “The impact of animated interface agents: a review of empirical research”, International Journal of Human Computer Studies, 52, (2000), pp 1-22. [9] B.J. Fogg, “Persuasive Computers: Perspectives and research directions”, Proceedings of the CH1’98, Conference of the ACM/SIGCHI, New York: ACM Press, (1998), pp. 225-232. (10) B.J. Fogg, Persuasive Technology: Using Computers To Change What We Think and Do, San Francisco: Morgan Kaufman, (2002). (11) Foner, What's an Agent, Anyway? http://foner.www.media.mit.edu/people/foner/Julia/Jul ia.html Autonomy [12] H.H. Friedman, and L. Friedman, “Endorser effectiveness by product type”, Journal of Advertising Research, 19, (1979), pp. 63-71. [13] J. Hagel, and J. Rayport, “The coming battle for customer information”, McKinsey Quarterly, 3, (1997), pp. 64-77. [14] C.E. Heckman, and J.O. Wobbrock, “Put your best face forward: anthropomorphic agents, ecommerce consumers, and the law”, Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Autonomous Agents (Agents 2000), Barcelona, Spain, June, (2000), pp. 435-442. [15] K. Isbister, and C. Nass, “Consistency of personality in interactive characters: Verbal cues, nonverbal cues, and user characteristics”, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53, (2000), pp. 251-267. [16] K. Isbister, H. Nakanishi, T. Ishida, and C. Nass, “Helper Agent: Designing an assistant for humanhuman interaction”, Proceedings of CHI 2000, (2000), pp. 57-65. 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 9 Proceedings of the 37th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2004 [17] M.A. Kamins, “An investigation into the 'matchup’ hypothesis in celebrity advertising: When beauty may only be skin deep”, Journal of Advertising, 19, (1990), pp. 4-13. [18] T. Koda, and P. Maes, “Agents with faces: the effect of personification”, Proceedings of the 5th IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Communication (RO-MAN’96), (1996), pp. 189-194. [19] J.C. Lester, S.T. Barlow, S.A. Converse, B.A. Stone, S.E. Kahler, and R.S. Bhogal, “The Persona Effect: Affective impact of animated pedagogical agents”, Proceedings of CHI '97. Atlanta GA: ACM Press, (1997), pp. 359-366. [20] H. McBreen, P. Shad, M. Jack, and P. Wyard, “Experimental assessment of the effectiveness of synthetic personae for multi-modal e-retail applications”, Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Autonomous Agents (Agents-2000), (2000), pp. 39-45. [21] P. McGoldrick, Retail Marketing. 2nd Edition, Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education, (2002). [22] S. Misra, “Celebrity spokesperson and brand congruence: An assessment of recall and affect”, Journal of Business Research, 21, (1990), pp. 195-213. [23] L. O'Malley, and C. Tynan, “Relationship marketing in consumer markets: rhetoric or reality?” European Journal of Marketing, 34(7), (2000), pp. 797-815. [30] Y. Tsal, “Effects of verbal and visual information on brand attitudes”, Advances in Consumer Research, 12, (1985), pp. 265-267. [31] M. Walker, L. Langmeyer, and D. Langmeyer, “Commentary - Celebrity Endorsers: do you get what you pay for?” Journal of Services Marketing, 6(4), (1992), pp. 35-42. [32] M. Witkowski, B. Neville, and J. Pitt, “Agent mediated retailing in the connected local community”, Interacting with Computers, 28, (2003), pp. 5-32. [33] P. Wright, R. Milroy, and A. Lickorish, “Static and animated graphics in learning from interactive texts”, European Journal of Psychology of Education, 14(2), June, (1999), pp. 203-224. [34] R. Zajonc, “Social interaction”, Science, 149, (1965), pp.269-274. i http://www.cctc.com http://nicorette.quit.com/main.asp iii http://portal.extempo.com/arena/index .asp?page=index&type=category_index ii Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments; to our respondents for their time and input; and for the support of the Manchester Retail Research Forum and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (UK) (grant no: GR/R66890/01) [24] S. Parise, S. Kiesler, L. Sproull, and K. Waters, “My partner is a real dog: Cooperation with social agents”, Proceedings of Computer Supported Cooperative Work '96, Cambridge, MA: ACM Press, (1996), pp. 399-408. [25] B. Reeves, and C. Nass, The Media Equation: How people treat computers, television, and new media like real people and places, New York: Cambridge University Press, (1996). [26] J. Riegelsberger, M.A. Sasse, and J. McCarthy, “Shiny happy people building trust? photos on ecommerce websites and consumer trust”, Proceedings of CHI2003, 5-10 April, Ft. Lauderdale, FL, US, (2003), pp.121-128. [27] M.R. Solomon, R. Ashmore, and L. Longo, “The Beauty Match-Up Hypothesis: Congruence between types of beauty and product images in advertising”, Journal of Advertising, (1992), 21, pp. 23-34. [28] L. Sproull, M. Subramani, S. Kiesler, J.H. Walker, and K. Waters, “When the interface is a face”. Human Computer Interaction, 11, (1996) pp 97-124. [29] B.D. Till, and M. Busler, “The Match-up Hypothesis: Physical attraction, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitudes, purchase intent, and brand beliefs”, Journal of Advertising, 29(3), (2001), pp.113. 0-7695-2056-1/04 $17.00 (C) 2004 IEEE 10