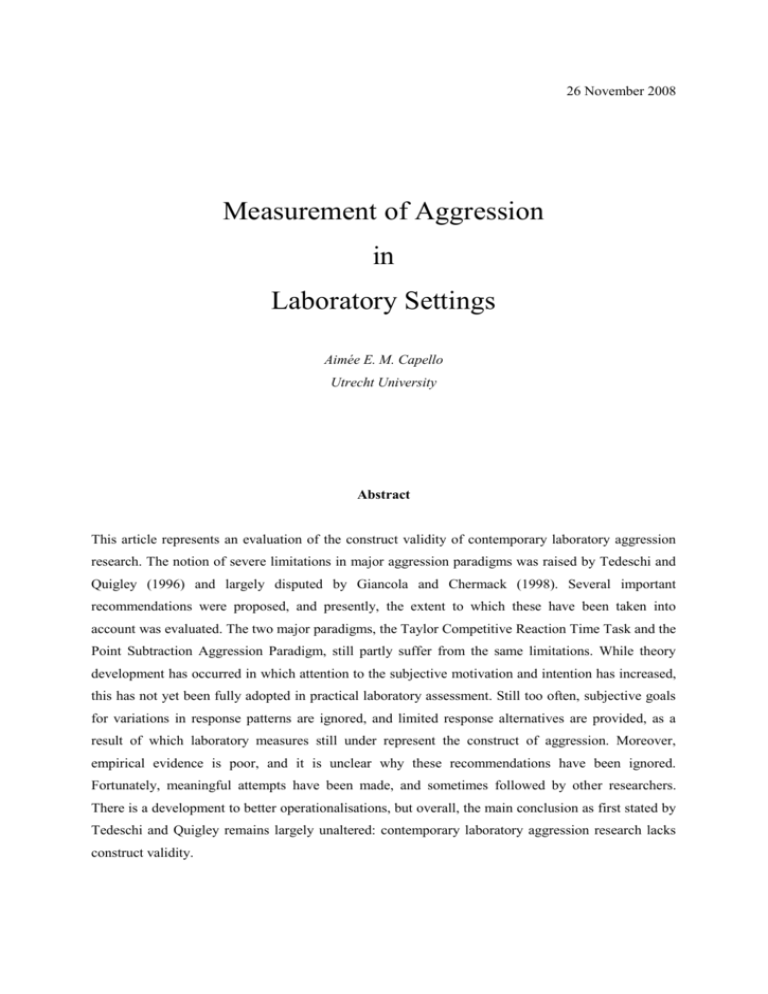

Open Access version via Utrecht University Repository

advertisement