Banha University Faculty of Arts English Department A Guiding

advertisement

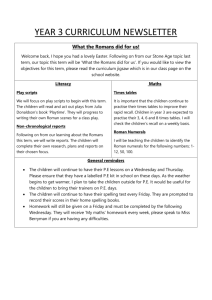

ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Banha University Faculty of Arts English Department A Guiding Model Answer for First Grade Civilization June 11 (Year 2011) Faculty of Arts Prepared by Mohammad Badr AlDeen Al-Hussini Hassan Mansour, Ph.D. University of Nevada, Reno (USA) 1 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ First Grade Department of English Second Term (Year 2010/2011) Time: 3 hours Civilization ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Respond to the following questions: 1. Choose three only of the following questions: A. The early Britons. B. The Anglo Saxon kingdom of England. C. Feudal England under the Normans. D. Henry III and the origin of parliament. 2. Write about two only of the following subjects: A. The reign of King Offa and the coming of Scandinavians. B. Alfred of Wessex. C. Beowulf and The Vision of Piers Plowman. 3. Write an essay about the Romans in England: their coming, their conquest, and Christianity in Britain. Good Luck Mohammad Badr AlDeen Al-Hussini Hassan Mansour 2 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Answers Question One (A): Write on the early Britons? Answer: The Britons (sometimes Brythons or British) were the Celtic people living in Great Britain from the Iron Age through the Early Middle Ages. They spoke the Insular Celtic language known as British or Brythonic. They lived throughout Britain south of about the Firth of Forth; after the 5th century Britons also migrated to continental Europe, where they established the settlements of Brittany in France and the obscure Britonia in what is now Galicia, Spain. Their relationship to the Picts north of the Forth has been the subject of much discussion, though most scholars accept that the Pictish language during this time was a Brythonic language related to, but perhaps distinct from, British. The earliest evidence for the Britons and their language in historical sources dates to the Iron Age. After the Roman conquest of 43 AD, a Romano-British culture began to emerge. With the advent of the Anglo-Saxon settlement in the 5th century, however, the culture and language of the Britons began to fragment. By the 11th century their descendants had split into distinct groups, and are generally discussed separately as the Welsh, Cornish, Bretons, and the people of the Hen Ogledd ("Old North"). The British language developed into the distinct branches of Welsh, Cornish, Breton, and Cumbric. Question One (B): Write on the Anglo Saxon kingdom of England? Answer: Anglo-Saxon England refers to the period of the history of England that lasts from the end of Roman Britain and the establishment of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 5th century until the Norman conquest of England in 1066. Anglo-Saxon is a general term that refers to the Germanic settlers who came to Britain during the 5th and 6th centuries, including Angles, Saxons, Frisii and Jutes. Anglo-Saxon England until the 9th century was dominated by the Heptarchy, the kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex and Wessex. These kingdoms were pagan during the early period, but were converted to Christianity during the 7th century. Paganism had a final stronghold in a period of Mercian hegemony during the 640s, ending with the death of King Penda in 655. Facing the threat of Viking invasions, the House of Wessex became dominant during the 9th century, under the rule of Alfred the Great. During the 10th century, the individual kingdoms unified under the rule of Wessex into the Kingdom of England, which 3 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ stood opposed to the Danelaw, the Viking kingdoms established from the 9th century in the North of England and the East Midlands. The Kingdom of England fell in the Viking invasion from Denmark in 1013, and was ruled by the House of Denmark until 1042, when the Anglo-Saxon House of Wessex was restored. The last Anglo-Saxon king, Harold Godwinson, fell at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. As the Roman occupation of Britain was coming to an end, Constantine III withdrew the remains of the army, in reaction to the barbarian invasion of Europe. The Romano-British leaders were faced with an increasing security problem from sea borne raids, particularly by Picts on the East coast of England. The expedient adopted by the Romano-British leaders was to enlist the help of Anglo-Saxon mercenaries (known as foederati), to whom they ceded territory. In about AD 442 the Anglo-Saxons mutinied, apparently because they had not been paid. The British responded by appealing to the Roman commander of the Western empire Aëtius for help (a document known as the Groans of the Britons), even though Honorius, the Western Roman Emperor, had written to the British civitas in or about AD 410 telling them to look to their own defence. There then followed several years of fighting between the British and the Anglo-Saxons. The fighting continued until around AD 500, when, at the Battle of Mount Badon, the Britons inflicted a severe defeat on the Anglo-Saxons. After the defeat of the Anglo-Saxons by the British at the Battle of Mount Badon in c.AD 500, where according to Gildas the British resistance was led by a man called Ambrosius Aurelianus, Anglo-Saxon migration was temporarly stemmed. Gildas said that this was "forty-four years and one month" after the arrival of the Saxons, and was also the year of his birth. He said that a time of great prosperity followed. But, despite the lull, the Anglo-Saxons took control of Sussex, Kent, East Anglia and part of Yorkshire; while the West Saxons founded a kingdom in Hampshire under the leadership of Cerdic, around AD 520. However, it was to be 50 years before the Anglo-Saxons began further major advances. In the intervening years the Britons exhausted themselves with civil war, internal disputes, and general unrest: which was the inspiration behind Gildas's book De Excidio Britanniae (The Ruin of Britain). The next major campaign against the Britons was in AD 577, led by Cealin, king of Wessex, whose campaigns succeeded in taking Cirencester, Gloucester and Bath (known as the Battle of Dyrham). This expansion of Wessex ended abruptly when the Anglo-Saxons started fighting amongst themselves, and resulted in Cealin eventually having to retreat to his original territory. He was then replaced by Ceol (who was possibly his nephew): Cealin was killed the following year, but the annals do not specify by whom. Cirencester subsequently became an Anglo-Saxon kingdom under the overlordship of the Mercians, rather than Wessex. If the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles are to be believed, the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which eventually merged to become England were founded when small fleets of 4 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ three or five ships of invaders arrived at various points around the coast of England to fight the Sub-Roman British, and conquered their lands. As Margaret Gelling points out, in the context of place name evidence, what actually happened between the departure of the Romans and the coming of the Normans is the subject of much disagreement by historians. The arrival of the Anglo-Saxons into Britain can be seen in the context of a general movement of German people around Europe between the years 300 and 700, known as the Migration period. In the same period there were migrations of Britons to the Amorican peninsula: initially around AD 383 during Roman rule, but also c.460 and the 540s and 550s; the 460s migration is thought to be a reaction to the fighting during the Anglo-Saxon mutiny between about 450 to 500, as was the migration to Britonia (modern day Galicia, in northwest Spain) at about the same time. The historian Peter Hunter-Blair expounded what is now regarded as the traditional view of the Anglo-Saxon arrival in Britain. He suggested a mass immigration, fighting and driving the Sub-Roman Britons off their land and into the western extremities of the islands, and into the Breton and Iberian peninsulas. The modern view is of co-existence between the British and the Anglo-Saxons. Discussions and analysis still continues on the size of the migration, and whether it was a small elite band of AngloSaxons who came in and took over the running of the country, or a mass migration of peoples who overwhelmed the Britons. Question One (D): Write on Henry III and the origin of parliament? Answer: It is to these years under Henry III that historians turn for the earliest signs of the major contribution of the English Middle Ages to the West—the development of Parliament. The word parliament comes from French and simply means a “talk” or “parley”—a conference of any kind. The word was applied in France to that part of the curia regis which acted as a court of justice. In England during the thirteenth century, the word often refers to the assemblies summoned by the king, especially those that were to hear petitions for legal redress. In short, a parliament in England in the thirteenth century was much like the parlement in France—a session of the king’s large council acting as a court of justice. The Norman kings made attendance at sessions of the great council compulsory; it was the king’s privilege, not his duty, to receive counsel, and it was the vassal’s duty, not his privilege, to offer it. But by requiring the barons to help govern England, the kings strengthened the assembly of vassals, the great council. The feeling gradually grew that the king must consult the council. Yet the kings generally consulted only the small council of their permanent advisers; the great council met only occasionally and when summoned by the king. 5 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ The barons who sat on the great council thus developed a sense of being excluded from the work of government in which they felt entitled to participate. It was baronial discontent that led to the troubles under Henry III. When the barons took over the government in 1258, they determined that the great council should meet three times a year, and they called it a parliament. When Henry III regained power, he continued to summon the feudal magnates to the great council, to parliament. The increasing prosperity of England in the thirteenth century had enriched many members of the landed gentry who were not necessarily the king’s direct vassals. The inhabitants of the towns had also increased in number and importance with the growth of trade. Representatives of these newly important classes in country and town now began to attend parliament at the king’s summons. They were the knights of the shire, two from each shire, and the burgesses of the towns. Recent research has made it seem probable that the chief reason for the king’s summons to the shire and town representatives was his need for money. By the thirteenth century the sources of royal income were not enough to pay the king’s ever-mounting bills. Thus he was obliged, according to feudal custom, to ask for “gracious aids” from his vassals. These aids were in the form of percentages of personal property, and the vassals had to assent to their collection. So large and so numerous were the aids that the king’s immediate vassals naturally collected what they could from their vassals to help make up the sums. Since these subvassals would contribute such a goodly part of the aid, they, too, came to feel that they should consent to the levies. The first occasion for which there is clear evidence of the king summoning subvassals for this purpose was the meeting of the great council in 1254. The towns also came to feel that they should be consulted on taxes, since in practice they could often negotiate with the royal authorities for a reduction in the levy imposed on them. Burgesses of some towns were included for the first time in Simon de Montfort’s “Parliament” of 1265. Knights of the shire also attended this meeting because Simon apparently wanted to muster the widest possible support for his program. But only known supporters of Simon were invited to attend the Parliament. Question Two (B): Write on Alfred of Wessex? Answer: Alfred The Great, king of Wessex (871–899), a Saxon kingdom in southwestern England. He prevented England from falling to the Danes and promoted learning and literacy. Compilation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle began during his reign, c. 890. 6 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ When he was born, it must have seemed unlikely that Alfred would become king, since he had four older brothers; he said that he never desired royal power. Perhaps a scholar’s life would have contented him. His mother early aroused his interest in English poetry, and from his boyhood he also hankered after Latin learning, possibly stimulated by visits to Rome in 853 and 855. It is possible also that he was aware of and admired the great Frankish king Charlemagne, who had at the beginning of the century revived learning in his realm. Alfred had no opportunity to acquire the education he sought, however, until much later in life. He probably received the education in military arts normal for a young man of rank. He first appeared on active service in 868, when he and his brother, King Aethelred (Ethelred) I, went to help Burgred of Mercia against a great Danish army that had landed in East Anglia in 865 and taken possession of Northumbria in 867. The Danes refused to give battle, and peace was made. In this year Alfred married Ealhswith, descended through her mother from Mercian kings. Late in 871, the Danes invaded Wessex, and Aethelred and Alfred fought several battles with them. Aethelred died in 871 and Alfred succeeded him. After an unsuccessful battle at Wilton he made peace. It was probably the quality of the West Saxon resistance that discouraged Danish attacks for five years. In 876 the Danes again advanced on Wessex: they retired in 877 having accomplished little, but a surprise attack in January 878 came near to success. The Danes established themselves at Chippenham, and the West Saxons submitted “except King Alfred.” He harassed the Danes from a fort in the Somerset marshes, and until seven weeks after Easter he secretly assembled an army, which defeated them at the Battle of Edington. They surrendered, and their king, Guthrum, was baptized, Alfred standing as sponsor; the following year they settled in East Anglia. Wessex was never again in such danger. Alfred had a respite from fighting until 885, when he repelled an invasion of Kent by a Danish army, supported by the East Anglian Danes. In 886 he took the offensive and captured London, a success that brought all the English not under Danish rule to accept him as king. The possession of London also made possible the reconquest of the Danish territories in his son’s reign, and Alfred may have been preparing for this, though he could make no further advance himself. He had to meet a serious attack by a large Danish force from the European continent in 892, and it was not until 896 that it gave up the struggle. The failure of the Danes to make any more advances against Alfred was largely a result of the defensive measures he undertook during the war. Old forts were strengthened and new ones built at strategic sites, and arrangements were made for their continual manning. Alfred reorganized his army and used ships against the invaders as early as 875. Later he had larger ships built to his own design for use against the coastal raids that continued even after 896. Wise diplomacy also helped Alfred’s defense. He maintained 7 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ friendly relations with Mercia and Wales; Welsh rulers sought his support and supplied some troops for his army in 893. Alfred succeeded in government as well as at war. He was a wise administrator, organizing his finances and the service due from his thanes (noble followers). He scrutinized the administration of justice and took steps to ensure the protection of the weak from oppression by ignorant or corrupt judges. He promulgated an important code of laws, after studying the principles of lawgiving in the Book of Exodus and the codes of Aethelbert of Kent, Ine of Wessex, and Offa of Mercia, again with special attention to the protection of the weak and dependent. While avoiding unnecessary changes in custom, he limited the practice of the blood feud and imposed heavy penalties for breach of oath or pledge. Alfred is most exceptional, however, not for his generalship or his administration but for his attitude toward learning. He shared the contemporary view that Viking raids were a divine punishment for the people’s sins, and he attributed these to the decline of learning, for only through learning could men acquire wisdom and live in accordance with God’s will. Hence, in the lull from attack between 878 and 885, he invited scholars to his court from Mercia, Wales, and the European continent. He learned Latin himself and began to translate Latin books into English in 887. He directed that all young freemen of adequate means must learn to read English, and, by his own translations and those of his helpers, he made available English versions of “those books most necessary for all men to know,” books that would lead them to wisdom and virtue. The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, by the English historian Bede, and the Seven Books of Histories Against the Pagans, by Paulus Orosius, a 5th-century theologian revealed the divine purpose in history. Alfred’s translation of the Pastoral Care of St. Gregory I, the great 6th-century pope, provided a manual for priests in the instruction of their flocks, and a translation by Bishop Werferth of Gregory’s Dialogues supplied edifying reading on holy men. Alfred’s rendering of the Soliloquies of the 5th-century theologian St. Augustine of Hippo, to which he added material from other works of the Fathers of the Church, discussed problems concerning faith and reason and the nature of eternal life. This translation deserves to be studied in its own right, as does his rendering of Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy. In considering what is true happiness and the relation of providence to faith and of predestination to free will, Alfred does not fully accept Boethius’ position but depends more on the early Fathers. In both works, additions include parallels from contemporary conditions, sometimes revealing his views on the social order and the duties of kingship. Alfred wrote for the benefit of his people, but he was also deeply interested in theological problems for their own sake and commissioned the first of the translations, Gregory’s Dialogues, “that in the midst of earthly troubles he might sometimes think of heavenly things.” He may also have done a translation of the first 50 psalms. Though not Alfred’s work, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, one of the greatest sources of information about Saxon England, which began to be circulated about 890, may have its origin in the intellectual 8 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ interests awakened by the revival of learning under him. His reign also saw activity in building and in art, and foreign craftsmen were attracted to his court. In one of his endeavors, however, Alfred had little success; he tried to revive monasticism, founding a monastery and a nunnery, but there was little enthusiasm in England for the monastic life until after the revivals on the European continent in the next century. Alfred was never forgotten: his memory lived on through the Middle Ages and in legend as that of a king who won victory in apparently hopeless circumstances and as a wise lawgiver. Some of his works were copied as late as the 12th century. Modern studies have increased knowledge of him but have not altered in its essentials the medieval conception of a great king. Question Two (C): Write on Beowulf and The Vision of Piers Plowman? Answer: In Beowulf, as clearly as in the Greek epics, the oral origin of the poem is made explicit by the poet's own references to oral poems in the narrative, so that Beowulf is conservative in its view of poetry as well as in its historical outlook. The origin of a poem such as Beowulf can be viewed within the Old English epic in the important scene starting at line 867. The sort of instant praise-poetry is not, however, simply a direct restatement of the hero's deed. The "evoker of stories" instead praises Beowulf by beginning with the story of Sigemund, who had a similar exploit (killing a dragon), and he ends with a mention of the blameworthy Heremod, an early Danish king, the complete opposite of Beowulf. There is no mention of the way in which he actually praised the maiming of Grendel by the contemporary hero; it could well be that what the old retainer composed in fact made little or no reference to Beowulf. Surprising as this might seem, it would fit with what can be seen in the Iliad, in the episode just mentioned above: the present is continually set into its past heroic context in this oral traditional material. That something like the horseback poem of the retainer could have occurred in early times is suggested by the Roman historian Tacitus' account of Germanic tribesmen, who, he reported, sang the histories of their ancestors before battles and at night in their camps. This urge to turn the past into incentive for the present lies at the root of heroic poetry as well as praise-poetry, the kernel form of the epic. In the song of the retainer, which resembles Greek praise-poetry in its use of a "negative foil" figure (the blamed character), one can see the kernel blossoming into a full-fledged narrative. As in the analysis of the Greek epics, the notion of type-scene and theme proves useful in establishing connections between Beowulf and oral composition. The analysis of the low-level formula—the repeated phrase or word—is less conclusive; Beowulf appears 9 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ to be oral because it appears to have a high percentage of formulas or formula-types (repeated syntactical groupings such as epithet and noun), but the statistical method should not be relied on completely. It has recently been shown that poems known to have been written and signed by Cynewulf, probably in the ninth century, would have to be classified as "oral" if the same counting methods were applied. It could be that both Cynewulf's poems and the epic Beowulf are transitional products of the meeting of an oral tradition with a learned, Christianized, literate society. This would explain the seemingly incongruous elements of Christian faith in the heroic poem. Whatever the results of the diction-oriented analysis, the occurrence of traditional type-scenes and themes in Beowulf is important in itself and may be taken to show the poem's oral heritage. Beowulf has its start in an arrangement of type-scenes remarkably like that of the Odyssey: a hero sets out by boat, is met on landing, is greeted and entertained, finds important information, and acts on it to the advancement of his own heroic career. Beowulf acts immediately; the poem is consequently much shorter. The Beowulf-poet handles themes with much dexterity. An example is the "taunt of Unferth" scene. The taunt is itself a genre in oral society, as the Homeric epics and modern African examples make clear. Here, the taunt is expanded to contain a thematic narrative remarkably like the theme of the surrounding poem: the underwater exploits of Beowulf. Unferth, a retainer of the Danish king Hrothgar, asks Beowulf on arrival whether he is the man who lost a swimming-match against Breca. Beowulf's reply is an elaborate, suspenseful narrative of a fight with sea-demons—the "correct" version of the story, unlike Unferth's, and a foreshadowing of his defeat of Grendel's mother beneath the lake. Beowulf (like Odysseus in the Odyssey) acts the part of the oral poet. Is it not significant, then, that he wins over the final monster, not with Unferth's donated sword Hrunting, but with the "blade of old-time" found in the den of Grendel, which only Beowulf among heroes can lift? His personal weapon, like his personal story, is the one to surpass the competing stories of heroic action; fame, in an oral culture, tunes out the noise of rumor. As well as containing hints of its own origin, Beowulf has one scene that might point to the kind of poetry that ultimately replaced it: the introduction of Grendel into the narrative describes his approach to the hall of the Danes where he had daily heard singing—and the song consists of nothing less than the creation of the world by God. Piers Plowman, the greatest Christian poem in the English language, comes from the second half of the fourteenth century and is thought, although not unanimously, to be the work of William Langland. Nothing certain is known about him; even his name comes doubtfully to us through a late tradition. All we know of his personal life is what he tells us of it in the poem, and that is little enough and open to doubt. In these uncertainties, it is best to begin by setting out such facts as there are, for they shed a light helpful to criticism on the poem, on the man who wrote it, and on how it was written and received. 10 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ The poem is cast in the form of a series of dream-visions told in the first person, as if dreamer and poet were one; and no sensitive reader can escape some impression of his personality and genius, or fail to wonder at the spiritual range and intensity of a mind that can generate a ferociously satirical laughter, a compassion as humane as Lear's, and a mystical sense of glory in God's love as expressed in the passion and resurrection of Christ. A wanderer named Will narrates Piers Plowman and is presented as the author of this epic poem. One day Will falls asleep and has a visionary dream in which members of all social classes appear in a field attending to their daily activities. At one end of the field is a tower and beneath the field is a dungeon. A woman named Holy Church tells Will that Truth (or God) inhabits the tower, and that Wrong (or Satan) resides in the dungeon. For Will to save his soul, explains Holy Church, he must follow Truth. Will then observes a dispute over arrangements for Lady Mede, who represents Reward, to marry False. The matter is brought to the king, who suggests that Lady Mede marry Conscience, but Conscience refuses. The king ultimately agrees to rule with the assistance of Reason and Conscience. In a second vision, Will encounters Reason delivering a sermon demanding society's repentance. Following Reason's speech, characters representing each of the seven deadly sins offer public confessions of wrongdoing. Society vows to seek out Truth; Piers Plowman, a farmer and follower of Truth, offers to lead the way if the audience will help him plow his small field. The joint effort fails, despite Hunger's attempts to motivate the workers. Piers vows to find Truth on his own. Following an argument with two friars regarding the nature of Do-Well and DoEvil, Will sustains a third vision. At the behest of Thought, Will explores Do-Well, DoBetter, and Do-Best. Along the way he meets Wit and his wife, Dame Study, who send him to Clergy and his wife, Scripture, who attempt to explain the stages Will has set out to explore. Unable to grasp their explanation, however, he falls asleep and enters a dreamwithin-a-dream whereby he begins to follow Fortune, Lust, and Recklessness. Scripture and Emperor Trajan set Will straight and he re-enters the original dream, in which he discusses such issues as education and religion with Imaginative. Will sustains a fourth vision several years later, in which he travels with Conscience and Patience. The three meet Hawkin the Active Man, who wears a dirty coat of Christendom. As a result of his discussion with the trio, Hawkin becomes aware of his sinfulness and reliance on grace and experiences a religious conversion. In a fifth vision, Will hears Anima's views on spiritual growth and charity. In another dream-within-adream, he again encounters Piers, who shows him the Tree of Charity inherent in every human. Will then encounters Faith, Hope, and the Good Samaritan, who represent, respectively, Abraham, Moses and Christ. The Samaritan discusses the Holy Trinity and stresses the necessity of repentance. 11 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Some time passes before Will's next vision, in which he witnesses the crucifixion. Awake, he chronicles his dreams up to this point and attends Easter mass with his family. He then sustains a seventh vision, in which Piers begins to build a house known as Unity. It is apparent at this point that Piers represents Jesus Christ and Unity the Christian church. In his final vision, Will encounters the Antichrist and sees sin attacking Unity. After an encounter with Old Age, he sees Unity attacked again, this time by Hypocrisy. Conscience insists that Piers can assist, but Peace allows Friar Flatterer to enter Unity to visit the sick. The Friar weakens Contrition, however, allowing the entry of Sloth and Pride. Conscience appeals to Clergy for assistance, only to find Clergy has been reduced to a daze by the Friar. As Conscience sets out to find Piers, Will awakens. Question Three: Write an essay about the Romans in England: their coming, their conquest, and Christianity in Britain? Answer: The written history of England really began in 55 BC when Julius Caesar led an expedition there. Caesar returned in 54 BC. Both times he defeated the Celts but he did not stay. Both times the Romans withdrew after the Celts agreed to pay annual tribute. The Romans invaded England again in 43 AD under Emperor Claudius. The Roman invasion force consisted of about 20,000 legionaries and about 20,000 auxiliary soldiers from the provinces of the Roman Empire. Aulus Plautius led them. The Romans landed somewhere in Southeast England and quickly prevailed against the Celtic army. The Celts could not match the discipline and training of the Roman army. A battle was fought on the River Medway, ending in Celtic defeat and withdrawal. The Romans chased them over the River Thames into Essex and within months of landing in England the Romans had captured the Celtic hill fort on the site of Colchester. Meanwhile other Roman forces marched into Sussex, where the local tribe, the Atrebates were friendly and offered no resistance. The Roman army then marched into the territory of another tribe, the Durotriges, in Dorchester and southern Somerset. Everywhere the Romans prevailed and that year 11 Celtic kings surrendered to Claudius. Normally if a Celtic king surrendered the Romans allowed him to remain as a puppet ruler. Aulus Plautius was made the first governor of Roman Britain. By 47 AD, the Romans were in control of England from the River Humber to the Estuary of the River Severn. However the war was not over. The Silures in South Wales and the Ordovices of North Wales continued to harass the Romans. Fighting between the Welsh tribes and the Romans continued for years. Meanwhile the Iceni tribe of East Anglia rebelled. At first the Romans allowed them to keep their kings and have some autonomy. However in c. 50 AD the Romans were 12 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ fighting in Wales and they were afraid the Iceni might stab them in the back. They ordered the Iceni to disarm, which provoked a rebellion. However the Romans easily crushed it. In the ensuing years the Romans alienated the Iceni by imposing heavy taxes. Then, when the king of the Iceni died he left his kingdom partly to his wife, Boudicca and partly to Emperor Nero Soon, however Nero wanted the kingdom all for himself. His men treated the Iceni very high-handedly and they provoked rebellion. This time a large part of the Roman army was fighting in Wales and the rebellion was, at first, successful. Led by Boudicca the Celts burned Colchester, St Albans and London. However the Romans rushed forces to deal with the rebellion. Although the Romans were outnumbered their superior discipline and tactics secured total victory. After the rebellion was crushed the Celts of southern and eastern England settled down and gradually accepted Roman rule. Then in 71-74 AD the Romans conquered the north of England. In the years 74-77 they conquered South Wales. Then in 77 AD Agricola was made governor of Britain. First he conquered North Wales. Then he turned his attention to what is now Scotland. By 81 AD the Romans had captured the area from the Clyde to the Forth. In 82 they advanced further north. In 83 the Romans won a great victory at Mons Graupius (it is not known exactly where that was). However in 86 the Romans withdrew from Scotland. In 122-126 the Emperor Hadrian built a great wall across the northern frontier of Roman Britain to keep out the people the Romans called the Picts. However under the Emperor Antonius Pius the Romans again invaded Scotland. In 42-43 they defeated the Picts. The Romans then built a wall of turf with a stone base to protect their conquests. However the Antonine Wall, as it was called, was abandoned about 163. The Roman army withdrew to Hadrian's Wall. By the middle of the 3rd century the Roman Empire was in decline. In the latter half of the 3rd century Saxons from Germany began raiding the east coast of Roman Britain. The Romans built a chain of forts along the coast, which they called the Saxon shore. The forts were commanded by an official called the Count of the Saxon shore and they contained both infantry and cavalry. However, the Saxon raids were, at first, no more than pin pricks and most of Roman Britain remained reasonably peaceful and prosperous. Then in 286, an admiral named Carauius seized power in Britain. For 7 years he ruled Britain as an emperor until Allectus, his finance minister, assassinated him. Allectus then ruled Britain until 296 when Constantius, Emperor of the Western Roman Empire invaded. Britain was then taken back into the Roman fold. In the 4th century the Roman Empire in the west went into serious economic and political decline. The populations of towns fell. Public baths and amphitheatres went out of use. In 367 Scots from Northern Ireland, Picts from Scotland and Saxons joined to raid Roman Britain and loot it. They overran Hadrian's Wall and killed the Count of the Saxon shore. However the Romans sent a man named Theodosius with reinforcements to restore 13 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ order. In 383 some Roman soldiers were withdrawn from Britain and the raiding grew worse. The last Roman troops left Britain in 407. In 410 the leaders of the Romano-Celts sent a letter to the Roman Emperor Honorius, appealing for help. However he had no troops to spare and he told the Britons they must defend themselves. Roman Britain split into separate kingdoms but the Romano-Celts continued to fight the Saxon raiders. Roman civilization slowly broke down. In the towns people stopped using coins and returned to barter. The populations of towns were already falling and this continued. Rich people left to be self-sufficient on their estates. Craftsmen went to live in the countryside. More and more space within the walls of towns was giving over to growing crops. Roman towns continued to be inhabited until the mid-5th century. Then most were abandoned. Some may not have been deserted completely. A small number may have still had a very small population who lived by farming land inside and outside the walls. However town life as such came to an end. In the 5th century Roman civilization in the countryside faded away. 14