Full paper - University of South Australia

advertisement

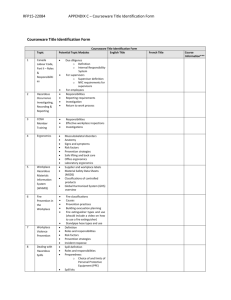

Checklists or context-bound evaluations for online learning in higher education? Peter Hosie Resources Development Learning Development Services Centre Edith Cowan University p.hosie@ecu.edu.au Ann Backhaus Resources Development Learning Development Services Centre Edith Cowan University a.backhaus@ecu.edu.au Renato Schibeci School of Education Murdoch University R.Schibeci@murdoch.edu.au This paper is in part derived from work done by Hosie, P., & Schibeci, R. (2001). Evaluating courseware: A need for more context– bound evaluations. Australian Educational Computing, 16, 2, 18-26. 1 Abstract: A case is made for using checklists and context-bound evaluations of online learning materials in higher education. Context-bound evaluations are a complementary and valuable alternative to traditional forms of evaluation of educational courseware, such as checklists. Context-bound approaches are useful for indicating the pedagogical quality of online learning materials that may be productively used in conjunction with checklists to evaluate online learning. Edith Cowan University has specifically developed checklists for assessing aspects of online pedagogical learning materials in higher education. Rather than simply arriving at a numeric score, these checklists are intended to be useful indicators of the areas where online learning materials are strong and to identify areas that may be deficient. These checklists are a valuable screening device to use when undertaking a context-bound evaluation of learning materials. The quality of the instructional design remains an important consideration in evaluating courseware. Comment and dissent is invited on the value of contextual evaluations to re-invigorate the debate over appropriate ways of evaluating online learning materials in higher education. Such information needs to be presented in a form that is accessible and useful for educational developers and researchers. Keywords: Context-bound evaluation Courseware evaluation Checklists Instructional design Higher education Online educational courseware 2 Introduction Students at all levels of education make extensive use of the Internet to assist with their learning. For example, they use e-mail, the World Wide Web, Internet, file transfers and remote systems access. While it is not possible to state with certainty the exact number of Internet users, in September 2002 one estimate placed it at approximately 605.60 million people (http://www.nua.ie/surveys/how_many_online/). The exact number of Internet users is not as important as the trend - the number of individuals accessing the Internet is growing exponentially. Mirroring this trend is an equally impressive demand for higher education via the Internet. Scores of institutions are planning to, or already have on offer, education via the Internet. This raises questions around courseware quality and methods of evaluation. This paper discusses the use of checklists and context-bound evaluations for online learning materials in Higher Education. Context-bound evaluations are a complementary and valuable alternative to traditional forms of evaluation, such as checklists (Hosie & Schebici, 2001). Context-bound approaches are useful for indicating the pedagogical quality of online learning materials. Edith Cowan University’s evaluative framework for courseware is a checklist that can be used in a context-bound evaluative manner, supplemented by sound instructional design principles. The Distance Education Context Taylor (2001) has identified four generations of distance education: Correspondence Model, based on print technology Multi-Media Model, based on print, audio and video technologies Telelearning Model, based on applications of telecommunications technologies Flexible Learning Model, based on synchronous communication As many universities begin to implement fourth generation initiatives, Taylor (2001) observes the emergence of a fifth generation of distance education1, the Intelligent Flexible Learning Model. According to Taylor: "The fifth generation of distance education is essentially a derivation of the fourth generation, which aims to capitalize on the features of the Internet and the Web" (p. 2). Taylor (2001) argued that the fifth generation has the potential to radically change the cost of providing online educational services as well as the educational experience through 3 the development and implementation of: automated courseware production systems, automated pedagogical advice systems, and automated business systems, the fifth generation of distance education has the potential to deliver a quantum leap in economies of scale and associated cost-effectiveness. Further, effective implementation of fifth generation distance education technology is likely not only to transform distance education, but also to transform the experience of on campus students (p. 4). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the various models of distance education that are relevant to the quality of teaching and learning (Taylor, 2001). The table also provides indicators of institutional variable costs (Taylor, Kemp & Burgess, 1993). 1 The term ‘Distance Education’ is almost a synonym for online learning in the USA. 4 Table 1 Models of distance education - a conceptual framework Models of Distance Education and Characteristics of Delivery Technologies Associated Delivery Technologies Flexibility Highly Refined Materials Advanced Interactive Delivery Institutional Variable Costs Approaching Zero Time Place Pace Yes Yes Yes Yes No No FIRST GENERATION The Correspondence Model Print SECOND GENERATION The Multi-media Model Print Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Audiotape Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Videotape Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Computer-based learning (eg. CML/CAL/IMM) Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Interactive video (disk and tape) Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Audioteleconferencing No No No No Yes No Videoconferencing No No No No Yes No Audiographic Communication No No No Yes Yes No Broadcast TV/Radio and Audioteleconferencing No No No Yes Yes No THIRD GENERATION The Telelearning Model FOURTH GENERATION The Flexible Learning Model Interactive multimedia (IMM) online Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Internet-based access to WWW resources Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Computer mediated communication Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No FIFTH GENERATION The Intelligent Flexible Learning Model Interactive multimedia (IMM) online Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Internet-based access to WWW resources Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Computer mediated communication, using automated response systems Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Campus portal access to institutional processes and resources Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes (Taylor, 2001) 5 With the emergence of the fifth generation came not only economies of scale (eg. variable costs, such as printing, decrease) but also flexibility. Flexible delivery refers to the degree to which learning is ‘flexible’ and depends upon: Flexibility in delivery - the range of course delivery options available; and Flexibility in options - the degree of student choice (tailored content, assessment options, learning style, modularity, etc) built into the course design. The MIT OpenCourseWare (MITOCW) Initiative Of all the recent innovations in educational technology, the path being forged by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is one of the most impressive and forward looking in scope. MIT is making the materials for most of its courses freely available on the Internet. At the time of this article, MIT had published 500 courses and has freely available on its OpenCourseWare web site the educational materials from 33 academic disciplines (http://ocw.mit.edu/index.html). MIT sees a variety of benefits coming from the MIT OpenCourseWare project: Institutions around the world can use OpenCourseWare materials as sources for curriculum development. Individual learners can draw upon the materials for self-study or supplementary use. The OpenCourseWare infrastructure can serve as a model for other institutions choosing to make content open and available. If other universities adopt this model, a vast collection of resources will facilitate idea exchange. A common repository of information will be available to stimulate educational innovation and cross-disciplinary educational ventures. (http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/nr/2001/ocw.html) Proponents of the OpenCourseWare approach (ie. offering information freely online) see a shift in focus. When students are able to acquire course content on the Internet, academics can concentrate on the actual process of teaching rather than simply the conveyance of information. Whilst of enormous value, the provision of high quality information (content) does not necessarily constitute an educational experience. Rather the impact also hinges on the 6 instructional design that creates the educational experience and the interactions that make up the teaching and learning experiences. MIT (wisely) does not claim to provide education on the Internet. What they freely provide on the Internet are core materials that underpin the much broader learning process. Despite the wide availability of materials, content alone does not necessarily equate to an educational experience for learners. Evaluations and Courseware: Shifting Ground, Outside Context Although evaluation should be a core quality activity in any Higher Education course, regardless of the medium, evaluation seems to be more often considered when the course includes some aspect of information technology. Little agreement exists among education colleagues about what evaluation involves and how it should be undertaken. A useful beginning is the set of categories for evaluating courseware proposed by Hawkridge (1990): descriptions, analyses, critiques and evaluations. A similar set of categories, as suggested by the OECD/CERI, was given by Cheung (1994): courseware description (a description of the main features of the courseware), courseware review (one individual's judgment about the courseware) and courseware evaluation (which must include actual use by the intended audience). Schibeci (1985) labelled this last process, "the acid test" in the courseware evaluation process because it is often considered to be a crucial test of the worth of educational courseware. Levine (1996) suggested that there are four aspects of evaluation, which apply also to courseware evaluation: "(a) courseware design; (b) the effects on courseware selection; (c) courseware implementation; and (d) the formation of a theoretical base for courseware use, including its effects on cognitive, social, and instructional process" (p. 261). Levine also noted the following about courseware evaluation as a field of study: "Although a vast amount of literature exists on this subject, a basis of agreed criteria is still lacking" (p. 261). Evaluation through Checklists Checklists and frameworks are two common approaches to predictive evaluation, which have received mixed reviews. Predictive evaluation has been defined by Squires and McDougall (1996) as "the assessment of the quality and potential of a software application before it is used with students" (p. 147). McDougall and Squire (1995) reviewed checklists for courseware evaluation and concluded that there is a role for checklists, such as the one given by Rowley and Slack (1997), in the formative evaluation of courseware, but not in its selection. McDougall and Squires (1995) also noted confusion between evaluation and selection. These two types of reviews serve very different but equally important purposes. 7 Analyses and critiques of computer courseware are commonly found in computer magazines. Similarly, educational courseware may be described, analysed, or critiqued. Does this type of evaluation provide a thorough analysis of educational courseware? Courseware evaluation needs to improve considerably to ensure the health of educational computing (Hardin & Patrick, 1998). Hawkridge (1990) points out that courseware was "only one element in a complex teaching and learning process" and that Higher Education academics "need to understand the context in which it was used" (p. 106). Context-Bound Evaluation Selecting courseware from a checklist is analogous to purchasing a car. A potential buyer is likely to have a mental checklist of what they want in a car (eg. air-conditioning, power steering, etc). A car may have all the features required in the checklist but the final decision will likely rest on how the car performs in relation to the purchaser's expectations. A prospective buyer is unlikely to make the final decision whether to buy until they have actually test driven the vehicle. Once the checklist of essential elements (relevance, cost, etc) of courseware is agreed, a context-bound evaluation may provide the visceral 'driving' experience a potential courseware purchaser seeks. Squires and McDougall (1996) noted recent acceptance by many educators of a "situated" view of learning, in which what is learned and how it is learned are not separated. They believed this view has important consequences for educational courseware evaluation. Importantly, they distinguish between predictive and interpretative evaluations: Predictive evaluation of software is the assessment of the quality and potential of a software application before it is used with students. Interpretative evaluation is concerned with assessing the observed use of an application by students. By definition, interpretative evaluation is conducted in context (p. 147). Levine (1996) suggested that "Observation of courseware in use can provide the basis for valid and effective evaluation for either formative or summative purposes" (p. 265). His review of courseware evaluation concluded as follows: Effective evaluation produces judgments that are context-related; regardless of the methodology used, it takes into account the pedagogical nature of courseware, the classroom milieu, the desired goals and the type of usage. Such evaluation is driven by educational needs, as reflected in the curricular, and by learning theories, rather than by technology (p. 266-7). Squires and McDougall (1996) offered an approach they label the "Perspectives Interactions 8 Paradigm", which is described as: a comprehensive framework for thinking about educational software and moves ... toward more educational uses such as learning processes, classroom activities, teacher roles, curriculum issues, and student responsibility for learning (p. 155). As Hawkridge (1990) asserted "you only understand the potential of courseware when you use it with learners" (p. 106). Obtaining this depth of understanding is best attained using a context-bound evaluation. Edith Cowan University's (ECU's) Framework for Evaluation ECU's framework for assessing the quality of online learning materials has been designed in the form of a checklist to provide a detailed description of the potential strengths and weaknesses of an online unit. The checklist is based on the determination of critical elements within three main areas, which describe the online setting: Pedagogies Resources Delivery strategies Tables 2 - 4 describe the critical elements within each of these sections and provide examples of how these elements can be manifested in online settings. 9 Pedagogies Pedagogies refer to the learning activities providing the foundation of the unit. Table 2 Pedagogies used in quality learning materials Learning Description Examples Authentic tasks The learning activities involve tasks that reflect the way in which the knowledge will be used in real life settings Problem-based learning activities using real-life contexts Learning tasks based in workplace settings Tasks are complex and sustained Tasks are set that require students to collaborate meaningfully Peer-evaluation, industry mentors Buddy systems employed to connect learners Teacher's role is one of coach and facilitator Inquiry and problem-based learning tasks Activities support and develop students' metacognitive skills Interesting, complex problems and activities rather than decontextualised theory Activities arouse students' curiosity and interests Activities and assessments linked to learners' own experiences Assessment is integrated with activities rather than separated from them Opportunity to present polished products rather than simple drafts Opportunities exist for students and their teachers to provide support on academic endeavour Opportunities for collaboration Learner-centred environments Engaging Meaningful assessments Students collaborate to create products that could not be produced individually There is a focus on student learning rather than teaching Learning environments and tasks challenge and motivate learners Authentic and integrated assessment is used to evaluate students' achievement After establishing the characteristics of the learning activities and assessments for the online unit, the characteristics of quality online resources can be considered. 10 Resources Resources refer to the content and information provided by the teachers for the learners. Table 3 Resources in quality learning materials demonstrate the following Learning Description Examples Accessibility Resources are organised in ways that make them easily accessed and located Resources are separate from learning tasks Intuitive and clear organisational strategies Resources are accessible in a non-linear format Where possible, resources should be current and based on regular literature reviews by lecturer Seminal works should not, however, be removed on the basis of age Use of primary resources is made wherever possible Resources should represent a variety of views (including conflicting views) to allow students the opportunity to assess the merit of arguments Resources provide for a range of perspectives Media are used to enrich data sources A variety of media is used where appropriate Book-on-screen approach should be avoided Equally, elaborate multimedia should be avoided when a simple diagram would be suitable Resources include a variety of cultural perspectives where possible Resources avoid gender and culturally exclusive terms Separation of local and generic content to facilitate customisation and adaptation Currency Richness Purposeful use of the media Inclusivity The age of resources are appropriate to the subject matter Resources reflect a rich variety of perspectives Media is suitable for the purpose intended Materials demonstrate social, cultural, and gender inclusivity The inclusion of quality online resources ensures that material content is current and accessible to a wide range of online learners. After establishing appropriate pedagogies and resources consideration can turn to delivery strategies. 11 Delivery Strategies Delivery strategies refer to the issues and considerations associated with the ways in which the course is delivered to the learners. Table 4 Delivery strategies in quality learning materials Learning Description Examples Reliable and robust interface The materials are accurate and error free in their operation Site is accessed reliably Navigation and orientation is seamless Many forms of online support for learners Students can find information on the website about the unit and its requirements Unit structure makes explicit relationships between learning outcomes, resources, activities and assessments Instructions clearly placed and always available The unit provides opportunities and encourages dialogue between students and between teachers and students Information and communication channels are open and inviting for students Students are encouraged to communicate with the teacher and other class members Appropriate bandwidth demands The materials are accessible without lengthy delays Graphics and other elements checked for download times Delivery formats employ strategies to optimise download times Equity and accessibility Unit materials and activities are accessible and available to all students Websites are accessible to disabled students Course requirements and resourcing made explicit to students ahead of the course Students are not hampered by firewalls or geographically sensitive restrictions Layout and presentation should incorporate common elements on the unit homepage reflecting a corporate style The corporate style should enhance rather than dictate a pedagogical approach Fonts, resolution etc. should conform to the corporate style where possible, but alternatives should be possible when needed Clear goals, directions and learning plans Communication Appropriate corporate style Unit information and expectation of student roles are clear Units adopt a corporate style for websites to ensure a benchmark quality of presentation The various attributes described in Tables 2-4 reflect constructivist learning principles. This constructivist approach is detailed in the Edith Cowan University Teaching and Learning Management Plan 2001 – 2003 (http://www.ecu.edu.au/LDS/directorate/ about/a_updated_tlmp.pdf). Thus the evaluation is strongly slanted to a constructivist perspective that “emphasizes the primacy of the learner's intentions, experience, and cognitive strategies" (Centre for the Advancement of University Teaching: http://nt.media.hku.hk/webcourse/mod1_paradigm.htm). 12 There needs to be space in this schema for the inclusion of a traditional instructivist approach, when appropriate, which "stresses the importance of objectives that exist apart from the learner." Ongoing debate continues between instructivist and constructivist approaches to teaching and learning (eg. Kafai & Resnick, 1996). Checklist for Predictive Evaluation - Gauging the Quality of Online Learning Materials The ECU evaluative checklist building on the ECU framework was developed by the Edith Cowan University Quality Online Working Group (March, 2001; Oliver & Herrington, 2001; Herrington, Herrington, Oliver, Stoney & Willis, 2001). This checklist details the essential components of quality online learning materials, providing a means of indicating the frequency of adherence (ie. never, sometimes and always). In addition to ECU academic staff using this tool to evaluate the quality of their online units, the checklist is used by peer evaluators, including academic colleagues within ECU, as part of a Quality Assurance review for online units and for guidance to the instructional designer of the learning resurrects. Additionally, students provide feedback on the quality of pedagogies, resources and delivery through an instrument called the UTEI (Unit and Teaching Evaluation Instrument). Although the UTEI is not designed to mirror the ECU checklist, the information provided by students translates into the critical elements covered in the ECU framework and checklist. The ECU checklist is not intended to be used to deliver a numeric score that provides a definitive evaluation of the courseware. Rather, this checklist is intended to reflect and to indicate areas of the materials that are pedagogically strong and identify weaknesses that need further attention. 13 Authentic tasks The learning activities involve tasks and contexts that reflect the way in which the knowledge will be used in real life settings Opportunities for collaboration The environment encourages and requires students to collaborate to create products that could not be produced individually Learner-centred environments There is a focus on activities that provide degrees of freedom, decisionmaking, reflection and self-regulation Engaging The learning activities challenge learners and provide some form of encouragement and motivation to support the engagement Meaningful assessments Authentic and integrated assessment is used to evaluate students' achievement Resources Accessibility The resources are organised in ways that make them easily accessed and located Currency The age of resources are appropriate to the subject matter Richness The resources reflect a rich variety of perspectives Strong use of the media The materials use the various media in appropriate ways Inclusivity The materials demonstrate cultural and gender inclusivity Delivery strategies Reliable and robust interface The materials are accurate and error free in their operation across all platforms and browsers Clear goals, directions and learning plans Unit information and expectation of student roles are clear Appropriate bandwidth demands The materials download without lengthy delays Equity and accessibility The unit materials and activities are considerate of students with visual impairment and physical disabilities Appropriate corporate style The materials use a style that is compatible with ECU policy and guidelines (Edith Cowan University Quality Online Working Group, March 2001) 14 always never Pedagogies sometimes Table 5 Edith Cowan University Quality Online learning quality checklist Courseware Evaluation: Sound Instructional Design Inherent in ECU's checklist is the quality of a course's instructional design that relates directly to context-bound evaluation. One major instructional design principle that is a significant consideration, but which receives scant attention in the literature, is the level of interaction desired by learners. While some learners prefer interaction and collaboration in learning tasks, others prefer solitary learning circumstances (Reiff, 1992). Learner engagement is another instructional design principle inherent to ECU’s checklist. According to Schank (1994) the future challenge for multimedia design lies in developing programs that actively engage the users. New courseware designs that do not rigidly structure learner responses need to be explored and evaluated to complement online instruction. Courseware Evaluation: An Online Reality Check Considerable expectation, hope (and hype) surround the Internet as an educational technology. Do evaluations indicate that online learning materials meet or exceed online educational expectations? Scanlon (1997) noted that few evaluation studies she reviewed did, "more than describe new and innovative uses of technology", and argued for "more critical accounts" of such endeavours (p. 84). Academics and practitioners are encouraged to contribute to a small but growing body of literature on context-bound evaluations of educational courseware for Higher Education. Large ongoing investments that universities are making in educational technology underpins the need for courseware evaluation. We need evidence rather than hype, despite the claims of Roblyer, Edwards and Havrilvk (1997) that: "Courseware quality was less troublesome now that it is in the early days of microcomputers when technical soundness frequently caused problems" (p. 116). This may well be true in a technical sense, but is educational courseware contributing to learning in a more significant way than earlier methods? If so, how is this occurring? Conclusion Evaluation of educational courseware remains an important activity in Higher Education. The need for effective evaluation of educational courseware is as necessary today as it was when computers were first introduced into Higher Education. A number of important issues emerge from this review of courseware evaluation. There are inherent limitations using a checklist approach to evaluating educational courseware. Checklists emphasize the technical attributes at the expense of broader classroom and laboratory activities, learning processes and other educational considerations. Additionally, 15 checklists generally evaluate in a vacuum, ie. outside of context. A checklist can be a useful screening device to use before undertaking a context-bound evaluation of courseware. A 'checklist' approach to evaluation can provide useful, if incomplete, information about educational courseware. Higher Education academics require additional evaluative data than that provided by checklist evaluation. More productive effort can be devoted to context-bound evaluations. 16 References _______ Centre for the Advancement of University Teaching. (http://nt.media.hku.hk/ webcourse/mod1_paradigm.htm) _______ Edith Cowan University Teaching and Learning Management Plan 2001 – 2003. (http://www.ecu.edu.au/LDS/directorate/about/a_updated_tlmp.pdf) _______ MIT OpenCourseWare. (http://ocw.mit.edu/index.html) _______ MIT OpenCourseWare benefits. (http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/nr/2001/ocw.html) _______ NUA Internet statistics. (http://www.nua.ie/surveys/how_many_online/) _______ Unpublished internal document developed by Edith Cowan University CTLC Quality Online Working Group, 15 March, 2001. Cheung, W.S. (1994). A new role for teachers: Software evaluation. In J. Wright and D. Benzie (Eds.), Exploring a new partnership: Children, teachers and teaching (pp. 191-199). Elsevier. Hardin, L., & Patrick, T.B. (1998). Content review of medical educational software assessments. Medical Teacher, 20 (3), 207-211. Hawkridge, D. (1990). Software for schools: British reviews in the late 1980s. In O. BoydBarrett and E. Scanlon (Eds.), Computers and learning (pp. 88-108). Wokingham: Addison-Wesley. Herrington, A., Herrington, J., Oliver, R., Stoney, S,. & Willis, J. (2001). Quality guidelines for online courses: The development of an instrument to audit online units. In (G. Kennedy, M. Keppell, C. McNaught & T. Petrovic (Eds.), Meeting at the crossroads: Proceedings of ASCILITE 2001 (pp. 263-270). Melbourne: The University of Melbourne. Hosie, P., & Schebici, R. (2001). Evaluating courseware: A need for more context–bound evaluations. Australian Educational Computing, 16, 2: 18-26. Kafai, Y., & Resnick, M. (Eds.). (1996). Constructionism in Practice: Designing, Thinking, and Learning in a Digital World. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Levine, T. (1996). Courseware evaluation. In T. Plomp and D. Ely (Eds.), International encyclopedia of educational technology (2nd ed.). Pergamon. 17 McDougall, A., & Squires, D. (1995). A critical examination of the checklist approach in software selection. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 12 (3), 263-274. Oliver, R., & Herrington, J. (2001). Teaching and learning online: A beginner's guide to elearning and e-teaching in higher education. Centre for Research in Information Technology and Communications, Edith Cowan University, Western Australia. Reiff, Judith C. (1992). Learning Styles: What Research Says to the Teacher Series, National Education Association of the United States, Washington D.C., 40 pp. (Taken from ALS 609: Seminar on College Science Teaching A Summary of Current Ideas on Learning Styles. http://www.uoregon.edu/~susankv/ALS609/learning.htm). Roblyer, M.D, Edwards, J., & Havriluk, M.A. (1997). Using software tutors and tools: Principles and strategies. Integrating educational technology into teaching (pp. 116126). N.J.: Prentice Hall. Rowley, J., & Slack, F. (1997). The evaluation of interface design on CD-ROMS. Online and CD-ROM Review, 21 (1), 3-14. Scanlon, E. (1997). Learning science on-line. Studies in Science Education, 30, 57-92. Schank, R.C. (1994). Active Learning Through Multimedia. IEEE MultiMedia, Spring, 69-78. Schibeci, R.A. (1985). Educational software: Good, bad and indifferent. Australian Science Teachers Journal, 32 (3), 23-27. Squires, D., & McDougall, A. (1996). Software evaluation: A situated approach. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 12, 146-161. Taylor, J.C. (2001). Fifth Generation Distance Education Australia. Keynote Address presented at the 20th ICDE World Conference, Düsseldorf, Germany, 1-5 April 2001. (http://www.fernuni-hagen.de/ICDE/D-2001/final/keynote_speeches/wednesday/ taylor_keynote.pdf) Taylor, J.C., Kemp, J.E., & Burgess, J.V. (1993). Mixed-mode approaches to industry training: Staff attitudes and cost effectiveness. Report produced for the Department of Employment, Education and Training's Evaluations and Investigations Program, Canberra. 18