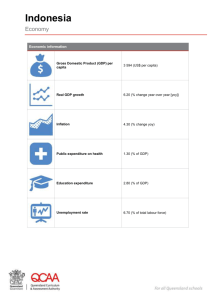

An independent active and creative foreign policy for Indonesia

advertisement

AN INDEPENDENT, ACTIVE AND CREATIVE FOREIGN POLICY FOR INDONESIA By : Dr. Dino Patti Djalal * This article was published in “Strategic Review : The Indonesian Journal of Leadership, Policy and World Affairs”, January – March 2012, volume 2, number 1. INDEPENDENT AND ACTIVE FOREIGN POLICY The biggest conceptual and operational challenge for Indonesia’s diplomacy is how to adapt our independent and active foreign policy to the new realities of a 21st century world order. Since the day it was enunciated by Vice President Muhammad Hatta in 1948, “independent and active” has proved to be a remarkably resilient foreign policy concept. Generations of policy makers have accepted it without question. Other diplomatic concepts have come and go – take your pick : diplomasi perjuangan, Jakarta-Hanoi-Pyongyang-Beijing axis, NEFOS versus OLDEFOS, development diplomacy, cultural diplomacy, concentric circles, total diplomacy, ecumenical diplomacy, and many others. Yet, “independent and active” stands apart and above as a concept that has withstood the test of time, and one which reflects the true color of Indonesian nationalism. Given its trans-generational credibility, it is certain that “independent and active” will continue to be a guiding principle for Indonesia’s international engagement in the 21st century. One reason why “independence and active” has survived generations is because it has always been left somewhat ambivalent. One may find it rather surprising that after decades, there has not been much attempt to define the precise elements of “independent and active”. The most common definition is that it entails “independence of judgment and freedom of action”. There is also the understanding that there can never be foreign military bases in Indonesia’s territory. Muhammad Hatta himself proposed the concept in the context of Indonesia’s efforts to navigate through the dangerous bipolar Cold War rivalry – “rowing between two reefs”, as he famously called it - and to ensure that Indonesia would become a subject rather an object in the international system. Still, the conceptual properties of “independence and active” foreign policy remain somewhat thin. My argument is this: for our time, being independent and active alone is not enough. As the operational terrain becomes more complex, Indonesian foreign policy actors will need additional guidance to perform their craft. The international system is no longer rigidly structured and divided as it was during the Cold War. Nations change, and relationships change. The world moves much faster, is much less predictable, and much more nuanced. As President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono aptly put it, diplomacy is no longer a question of “rowing between two reefs”, but a much more daunting challenge of “navigating in a turbulent ocean”. It remains critical for Indonesia to remain independent and maintain our activism, but we will need more than that. CREATIVE FOREIGN POLICY That additional quality is : the capacity to be “creative”. As many Indonesian diplomats have found, being “independent” is not so difficult – indeed, we tend to relish in taking a stand that is different from others. Being “active” is also easy to do – show up at various international forums and never hesitate to use the microphone. The problem is when we act independent for sake of being independent, and active for the sake of being seen as active. Indeed, I have been occasionally frustrated by those who would fight nail and tooth to maintain a certain position just because that has been the only policy line they know of, or those who like to be disagreeable as a way to be relevant. There are moments when the need to be “independent” is used as an excuse for inaction. With business as usual attitude, there is a danger that our foreign policy may become stale and unresponsive to fast changing events. In order to achieve results, ”independent and active” would have to be aided by a robust creative disposition. Indeed, the worst thing one can do to policy is to deprive it of creativity. A rigid diplomatic posture would lead us to run into a brick wall at a time when we need to be versatile. The 3 most powerful questions in creative diplomacy are: Why not ? What if ? What more ? I have found that the more diplomats ask these questions, the more they will generate ideas and solutions, and enhance our role and influence. An example of a “what if” moment would be when the Indonesian government, together with the Government of Norway, worked together to convene the Global Inter-Media Dialogue in the aftermath of the cartoon crisis in 2006. We knew that the fire needed to be put up, that Indonesia would have credibility to help, and that this was a tricky issue as dealt with the sacred freedom of speech. After asking numerous “what ifs”, Jakarta came up with the creative idea to convene a meeting between western and Islamic journalists to discuss the interrelationship between freedom of speech religious and cultural sensitivity. Beginning in Bali in 2006, it was a project that worked well, judging from the response of both the western and muslim journalists. The Global Inter-Media Dialogue continued for several years. A “why not” example would be when Indonesia announced the “26 - 41” formula at a time when climate debate was getting bogged down. There was gridlock in the negotiations between developed and developing countries, with neither side willing to move on a specific target of emission reduction. But while others say “why ?”, Indonesia asked “why not ?” Indonesia’s view was that developed country should take the lead, but developing countries should also do more. Hence, Indonesia broke ranks by announcing that we would reduce our emissions by 26 % in 2010 by our own means, and were willing to increase it to 41 % with international support. This 26-41 formula became a game changer. After Indonesia made its announcement, other major economies followed. A “what more” example would be when President Yudhoyono decided to engage Myanmar’s leader in a correspondence process. Indonesia wanted to be helpful to Myanmar while also strengthening good relations as fellow ASEAN members. The normal diplomatic channel was working, and Myanmar was actively taking part in ASEAN. But something more was needed. Hence, President Yudhoyono initiated a process of personal correspondence with Myanmar’s strong-man Senior General Than Shwe. This personal correspondence involved several letters back and forth, which provided useful channel of communication between the two leaders to share their thoughts in a no pressure format away from the media spotlight. In all these, Indonesia made diplomatic gains by thinking differently, by not following convention, and by taking some risks. WHY CREATIVE FOREIGN POLICY IS RELEVANT A creative foreign policy is entirely relevant because the international environment has become so crowded, complex and fast-changing that we need to constantly review our assumptions. When we cling to false assumptions, we end up making wrong strategic and tactical policy decisions. In a world marked by a myriad of problems, we must avoid a mindset that insists on policy retrenchment. We must pursue an open-minded approach that leads to game changing ideas. A creative foreign policy is necessary because our constituency has also become – well - very creative. Civil society is more dynamic than ever. The private sector is proliferating and full of innovation. The students are constantly pushing social and political boundaries. Stability is now defined by a persistent momentum towards progress, not a static state of affairs. Perhaps one of the most striking feature of the changing diplomatic landscape is the extent and depth of connectivity. In the middle of the 20th century, bilateral contacts were maintained by few Government officials, mainly through diplomatic note, telephone call or a visit. Contacts between citizens were limited and took place mainly by travel or letter writing – both of which required effort and somewhat costly. Today, direct contacts between citizens – through Facebook, Twitter, Linkd in, email, website, Youtube, bloggers forum – by far exceed contacts between government officials. Creative communities are finding their own ways and means to engage and collaborate. This is the new terrain with which our diplomats must keep up. Another reason for creative foreign policy is Indonesia’s rise as a regional power with global role. Our national interests are now frequently expressed in global terms – in the success of Doha round, in the G20, in UN reforms, in advancing climate negotiations. There is strong recognition that our national interests are tied to global issues – President Yudhoyono spoke about “the imperative of a new globalism”. To make a difference in such global arena, Indonesia needs to have diplomatic agility. We need to be intellectually competitive with fresh policy ideas in a very active global market place of ideas. It is no longer question of being merely being “independent” but whether such independence allows us to provide meaningful contribution to the global agenda. ELEMENTS OF CREATIVE FOREIGN POLICY A creative foreign policy requires certain mindset and predisposition. First, a forward-looking mindset. Those who look too much to the past will be stuck in nostalgics. As in driving, our job is to look through the front mirror to focus on the road ahead while keeping rear view mirror to be aware of what’s behind us. If we do it the other way around, we will run into accidents. The best example of this forward-looking approach is Indonesia’s relations with Timor Leste, where the two nations have been able to overcome a difficult painful past in order to pragmatically build very close relations across the board. Second, open mindedness. We cannot run creative foreign policy with closed mind and cynical attitude. We cannot afford to confuse potential friends as enemies, or to misread the goodwill of others. Our diplomats must avoid being married to a certain policy line just because it made sense 3 decades ago. Our foreign policy establishment must be open to – and driven by – new ideas. And our diplomatic schools must retool our diplomats to fight for national interests by sharpening their critical thinking and instinct for creative solutions. This is particularly important because in most diplomatic issues, the ability to come up with win-win solutions has become a necessary skill. Fourth, being opportunity driven, rather than fear driven. As President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono pointed out in Davos, in the 21st century we cannot afford to be overly dogmatic and ideological. There have been instances where lingering paranoia prevented us from seizing new opportunities and pursue more ambitious international cooperation. In this, both our diplomats as well as politicians need to reduce our predilection for wild conspiracy theories – which by the way, is also commonly found in Latin America and the Middle-East - and replace them with a higher risk appetite, cold calculations and rational judgment. This also means that our foreign policy establishment must encourage our diplomats to be more analysis heavy than information heavy. A critical part of being creative is knowing your limits. Indonesia is a middle power with limited diplomatic, military and economic resources. We cannot be involved in everything, but we can be relevant on certain things. In view of our finite resources, knowing how to prioritize and allocate resources to those priorities are essential to the efficacy of a creative foreign policy. Creative foreign policy has been given a big boost by the notion of ‘million friends and zero enemy’, enunciated by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono in 2005. This viewpoint is significant because Indonesian nationalism has always been connected to the presence of “enemy”. In the last 6 decades or so, various nations were designated as our nation’s enemies for one reason or another : Japan, The Netherlands, the United States, Great Britain, Malaysia, Singapore, Portugal, China. Thus, since the time of our independence, every generation had a foreign country which they called “enemy”. The “zero enemy” idea is unique because it indicates that presently no foreign state considers Indonesia as an enemy; and conversely, no state is considered by Indonesia as our enemy. Don’t get me wrong : we do have problems with our neighbors, and we do have disputes – many of them. But the quality of our engagement with these foreign governments cannot be described as hostile. Indeed, good neighbors quarrel and bicker all the time – the US and Mexico, Britain and France, Indonesia and Malaysia - but that does not turn them into enemies. If anything, problems only compel them into closer neighbors. The “million friends” idea is also unique. President Yudhoyono has stated that “our international engagement makes us better, safer, stronger”, implying that our internationalism and our nationalism are two sides of the same coin. The “million friends” entail many things : turning former foes into new friend; turning friend into partner; turning neighbors into family. “Zero enemy” does not automatically turn into a condition of “million friends”. This is why a key task for Indonesia’s diplomacy is take advantage of the condition of “zero enemy” to create an extensive network of friends and partners. The space is wide open for us to do this, especially with our enhanced international profile and the rapid power shifts that are taking place in the international system. Thus, the most important asset for Indonesian diplomats to develop is their lobbying and networking skills. When they do, they will happily find that every connection made equals at least one or more opportunity. ALL DIRECTION FOREIGN POLICY Creative foreign policy is also necessary in view of our pursuit of what President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono calls “all direction foreign policy”. “All direction foreign policy” is a post-Cold War 21st century organic extension of independent and active foreign policy. It means that to pursue our national interests and meet our global responsibilities, Indonesia must be able to effectively connect with all sides : east and west, north and south. All direction foreign policy signals that Indonesian diplomacy is again becoming assertive, global outward-looking. In the early years of our democratic transition, there was a moment when Indonesia became inward-looking (something that is likely to happen among present Arab spring countries as well). The political elites were tied up with pressing domestic issues and addressing instability. But those days are behind us for now. With democratic stability, especially since 2004, Indonesia regained speed in terms of regional and international activism – convening Asian-African Conference in 2005, hosting major UN Climate Conference in 2007, taking part in World Economic Forum in Davos, becoming chairman of ASEAN in 2011, and preparing for APEC chairman in 2013. Indonesia also developed an extensive network of strategic and comprehensive partnerships, : Australia, Japan, China, India, Pakistan, South Africa, the United States, Russia, Brazil, South Korea, Turkey, and several others. It is important to remember that in pursuing “all direction foreign policy”, becoming everybody’s friend does not mean pleasing and agreeing with everybody. It would be a terrible tragedy if Indonesia were to become shy and lose our edge as a principled diplomatic power. Foreign policy is first and foremost about promoting national interests, and not necessarily a popularity contest. The more friends we have, the more we need to take a clear stand on bilateral, regional and international issues, no matter how difficult and how many feathers we may ruffle. Our policy makers must always show leadership. Our diplomatic credibility, and our effectiveness, lies in our ability to consistently provide honest advise and constructive solutions to our friends. We must not be intimidated by size, pressures and threats, and we must live up to our hard-won legacy of independence of judgment and freedom of action. I would argue that this ability to utilize our expanding connections to advance our diplomatic impact is key to the success of million friends diplomacy. To harness the powers of creative foreign policy, Indonesian diplomats must hone what I would call partnership skills. This is because our diplomatic partnerships have significantly increasing and will continue to grow. But partnership is often easier to enter into than to develop. Partnership is not a momentary fad; it is a long-term commitment. We must treat our partners with the attention and resources they deserve, and this takes a special organizational and diplomatic skill. Our international partnerships must also be resilient to political changes at home, and when a partnership is under duress, our diplomats must have courage to fix it and defend the interests of such partnership rather than taking easy cover. This is what we expect from our partners, and this is what we need to do as well. Partnership skill also means that our diplomats must be proactive and assertive to ensure that there are balanced initiatives that come from each sides – not a partnership where we merely respond to the initiatives of our partners. Finally, I believe that there is no better moment for independent and active foreign policy to thrive than in our time. Our assets, our opportunities, our profile and our evolving diplomatic terrain combine all work in our favor. Indonesia is now on an upward trajectory – we are poised to become among the world’s top ten largest economies in the coming decades. Diplomacy is a key part of keeping Indonesia on that positive trajectory. In the 20th century, we benefitted a great deal from independent and active foreign policy. But we will need more than that in the coming years. It is time we pursue independent, active and creative foreign policy for the 21st century. (ends) The writer is Indonesia’s Ambassador to the United States and former Presidential spokesperson and special staff for international affairs.