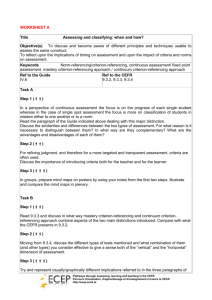

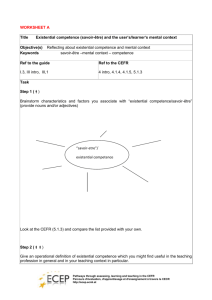

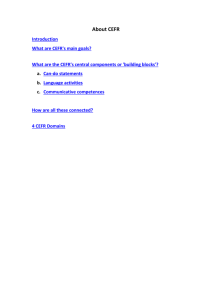

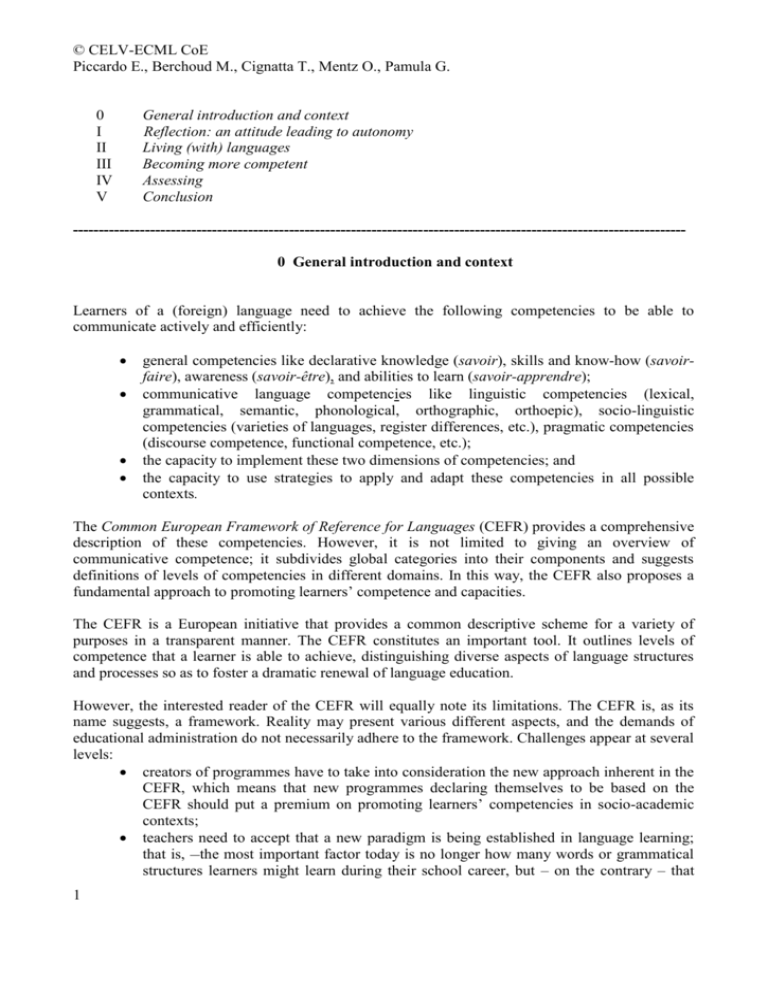

0 General introduction and context

advertisement