Cognitive Inhibitory Control as a Buffer Against

advertisement

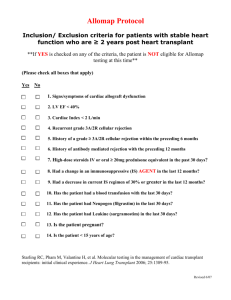

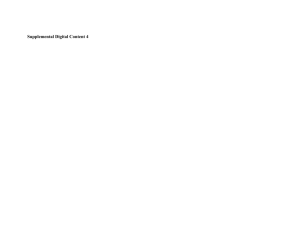

Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity Cognitive Inhibitory Control as a Buffer Against Rejection Sensitivity Özlem Ayduk Anett Gyurak University of California, Berkeley, USA Abstract People high in Rejection Sensitivity (RS) anxiously expect, readily perceive and react to perceived rejection with hostility. Previous research indicates, however, that self-control ability may serve as a protective factor against RS. Drawing from this research, this study (N = 40) hypothesized that cognitive inhibitory control – operationalized as resistance to interference in the Color Stroop paradigm – would moderate high RS individuals' attentional capture by rejection cues and their negative behavior towards partners. The hypothesized interaction between RS and cognitive inhibitory control was found such that high RS individuals with high cognitive inhibitory control showed less attentional capture by rejection and less hostile conflict behavior than high RS participants with low cognitive inhibitory control. The implications of these findings for protective mechanisms in RS dynamics are discussed. The Rejection Sensitivity (RS) model was developed to explain individual differences in people’s reactions to interpersonal rejection (Downey & Feldman, 1996). Extensive research to date has shown that because high RS people enter into relationships already anxiously expecting rejection, they show a readiness to perceive and overreact to rejection which compromises their own well-being and undermines their relationships (see Pietrzak, Downey & Ayduk, 2005 for review). However, new evidence is also emerging that self-control ability may attenuate high RS’s vulnerability to such negative outcomes (Ayduk, Mendoza-Denton, Mischel & Downey, Peake, Rodriguez, 2000). Building from this research, the goal of the present study was to examine whether cognitive inhibitory control ability – operationalized as resistance to interference in the Color Stroop paradigm – moderated high Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity RS individuals' attentional capture by rejection threat and their hostility towards relationship partners. Conceptualizing the processing dynamics of RS Consistent with attachment accounts of cognition and affect in relationships (e.g., Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Horney, 1937/1994), the RS model assumes that early exposure to rejection leads people to develop anxious expectations of rejection which then function as cognitive schemas to interpret and react to others in subsequent relationships (Downey, Bonica, & Rincon, 1999; Downey & Feldman, 1996; Downey, Khouri, & Feldman, 1997). It has been hypothesized and empirically demonstrated that the possibility of rejection leads to a sense of threat and foreboding in high RS individuals. For example, in the human startle probe paradigm (e.g., Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1990) high RS people show greater potentiation of their startle response in the presence of rejection cues, indicating over-activation of their defensive motivational system (Downey, Mougios, Ayduk, London, & Shoda, 2004). Additionally, high RS individuals show greater attentional capture by rejection stimuli in the emotional stroop paradigm (Berenson, Gyurak, Ayduk, & Downey, 2007) further suggesting that even minimal rejection cues activate threat-related defensive action tendencies in high RS people (Algom, Chajut, & Lev, 2004). Given such sensitivity to rejection cues, it is not surprising that high RS individuals show a greater tendency to interpret their partners' ambiguous or negative behaviors as intentional rejection (Downey & Feldman, 1996; Downey, Lebolt, Rincon, & Freitas, 1998). When high RS individuals perceive rejection, they are already in a state of heightened negative arousal and threat. Such threat related arousal has been shown to make people vulnerable to act on automatic, emotional, and impulsive behaviors at the expense of more cognitive and contemplative response options (e.g., Davis, 1992; Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999) and this process also manifests itself in the RS dynamics. For example, perceived rejection in high RS women makes thoughts of hostility automatically more accessible, which then translates into increased aggression towards their rejector (Ayduk, Downey, Testa, Yen, & Shoda, 1999). Likewise, high RS men in committed relationships are more at risk for violence against their partners than low RS men (Downey, Feldman, & Ayduk, 2000). These defensive behaviors elicit actual rejection from partners, creating a selffulfilling prophecy that maintains the high RS dynamics, and triggering an increase in depressive symptoms (Ayduk, Downey, & Kim, 2001; Downey, Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity Freitas, Michaelis & Khouri, 1998). Overall, this network of evidence supports the idea that even minimal cues relevant to rejection put high RS people in a defensive motivational state which sets off impulsive and sometimes destructive behaviors that undermine high RS people’s well-being and longterm relationship goals. Although high RS people’s increased vulnerability for negative outcomes is well-established by the evidence reviewed above, Ayduk and colleagues (Ayduk, et al., 2000; Ayduk, Zayas, Downey, Cole, Shoda, & Mischel, in press) reasoned that individual differences in the ability to delay immediate gratification assessed in Mischel’s classic preschool paradigm (Mischel, Shoda & Rodriguez, 1989) might also moderate this effect. Number of seconds children can wait for a preferred but delayed reward over a less preferred by immediately available rewards in this paradigm taps into children’s ability to inhibit impulsive tendencies (e.g., give up and settle for the immediately available reward), and down-regulate frustration via effective attention deployment strategies (e.g., distraction, reconstrual) en route to attaining valued long-term goals (see and Mischel & Ayduk, 2004, for a review). Furthermore, effective attention deployment during this preschool delay task has been shown to predict inhibitory control in a standard cognitive control task in adolescence (Eigsti, Zayas, Mischel, Shoda, Ayduk, & Dadlani, et al., 2006). Using performance in this paradigm as a measure of self-regulation, Ayduk and colleagues indeed found that whereas high RS individuals who were poor in delaying gratification as children were more vulnerable than low RS individuals for a wide range of negative life outcomes (low self-esteem, aggression, and borderline personality symptoms in adulthood), high RS people who were good delayers in preschool were buffered from these negative outcomes. The Color Stroop: A measure of cognitive inhibitory control The present study built from this literature and examined more directly the role of cognitive inhibitory control as a moderator of RS. Cognitive inhibitory control (also related to “attentional control") involves the ability to reduce conflict in information processing by overriding, or inhibiting, irrelevant salient information or prepotent responses in favor of the relevant items or responses (Posner & Rothbart, 2000). Interference tasks such as the Stroop are one of the most frequently used methods to measure cognitive inhibitory control. In the present study, we therefore operationalized Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity cognitive inhibitory control using the Color Stroop task (Stroop, 1935), in which participants are asked to name out loud the ink-color in which a word is written, rather than to read the word. When a color word (e.g. green) is printed in an incongruent ink color, reaction time is slower than when the color word and the ink color are congruent. Cohen, Dunbar, and McClelland (1990) argue that this task activates two mental pathways simultaneously, one more habitual that involves reading the word, and another, more effortful, which involves naming the ink color in which the word is written. Individuals are able to respond accurately and quickly to the extent that they can inhibit their habitual response (i.e., reading) and execute the more effortful one (i.e., color naming). Thus, individual differences in resistance to Color Stroop interference (i.e., shorter reaction times and fewer errors) are considered stable markers for cognitive inhibitory control ability (Block, 2005). Cognitive inhibitory control as a moderator of the effect of RS on attentional capture by rejection threat As described earlier, the RS model argues that because the possibility of rejection is so salient and threatening to high RS individuals, rejection cues may disproportionately capture their attention. This expectation was supported in a recent study that used the emotional stroop task (Berenson, et al. 2007). Emotional Stroop (Williams, Mathews, & MacLeod, 1996 for review) is a color-naming task where participants are presented with a list of emotion-eliciting words and asked to name the color of the ink that each word is printed in. The task’s most common use is to assess the extent to which stimuli relevant to personal concerns (e.g., insect related words for insect phobics) elicit automatic threat vigilance (or attentional capture by threat) (Algom et al., 2004). To the extent that stimuli are personally threatening, they elicit a defensive freezing response, which leads to slower color-naming times. Using this paradigm Berenson and colleagues (2007) found that high RS people to show slower response times when presented with rejectionrelated words, indicating heightened attentional capture by rejection threat. High RS people’s threat vigilance was specific to rejection words and was not found for threat stimuli unrelated to rejection (e.g., accident). In the current study, we examined whether the link between RS and attentional capture by rejection is moderated by individual differences in the Color Stroop performance. Based on the assumption that cognitive Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity inhibitory control enables individuals to inhibit prepotent, highly accessible reactions, we hypothesized that high RS individuals’ attentional capture by rejection threat should be attenuated to the extent they have high cognitive inhibitory control. Thus, in statistical terms, we expected an interaction between RS and cognitive inhibitory control in predicting response times to rejection words. Cognitive inhibitory control as a moderator of the effect of RS on conflict hostility Ample evidence links high RS to increased behavioral hostility and aggression in relationships (Ayduk, Gyurak, & Luerssen, in press; see Pietrzak et al., 2005 for a review). It has been argued before that when individuals experience negative interpersonal interactions such as conflicts, they face the dilemma of whether to act destructively to the partner in accordance with highly accessible, short-term goals (e.g., to hurt back, take revenge), or to behave more constructively, and accommodate the partner in accordance with long-term relationship goals (e.g., Arriaga & Rusbult, 1998; Yovetich & Rusbult, 1994). These accommodation dilemmas can be resolved in favor of constructive behaviors only when people have the cognitive resources to engage in controlled processes allowing them to consider their long-term consequences (Yovetich & Rusbult, 1994). When cognitive resources are depleted, responses to accommodation dilemmas are driven by more automatic, short-term considerations that favor self-centered destructive reactions (e.g., taking revenge, hurting back). Based on the foregoing analyses, we hypothesized in the current study that when faced with conflicts with partners – a potent elicitor of rejection concerns and hostility for high RS people (Downey et al., 1998), high RS individuals with high cognitive inhibitory control, compared to people with low cognitive inhibitory control, would be able to overcome their impulse to behave negatively, showing less hostility towards their partners. In statistical terms, we again expected an interaction between RS and cognitive inhibitory control in predicting hostile behavior towards partners in conflicts. Method Participants Participants were undergraduate students who were part of a larger study reported elsewhere (Berenson et al., 2007). Because we examined the moderating effects of cognitive inhibitory control on hostility towards Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity current partners, this study focuses on the subset of the participants who were involved in an ongoing relationship (N = 40, 50% male), reporting previously unpublished findings from this larger study. Participants completed the study in exchange for course credit. All had 20/20 or corrected 20/20 vision and no one in the sample was color-blind. Average age was 21.1years (SD = 6.1) with 37.5% of the sample being Asian, 40.0% Caucasian, 2.5% Hispanic, 2.5% African-American and 17.5 % multiple or other ethnicities. Procedure Participants completed the study individually. The session started with instructions for the Stroop tasks. Similar to methods used in neuropsyhological assessment, the Stroop words were written on cards. Participants were told that they would be shown a series of cards with words on them and asked to say out loud the color of the ink that each word was printed in if the word was printed in color ink, but to read the word itself if it was printed in black ink. This switching component was included to make the task reasonably difficult and challenging for college students (Wylie & Allport 2000). Participants were told to try to be as quick and accurate as possible as they were being timed and their errors were logged. For each card, the experimenter began timing when the first color name was read and stopped after the last color name was read. After the administration of the Stroop tasks, participants completed background questionnaires electronically on a computer. The questionnaires included the Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (RSQ) (Downey & Feldman, 1996), and a measure on hostile conflict tactics among several other measures, which were not the focus of this study. Measures & Materials Stroop Cards. There were 5 cards that comprised the Stroop tasks (details below): one for baseline color naming, one for Color Stroop, and three for Emotional Stroop. The baseline card was always administered first. The rest were presented in random order. The baseline color naming card contained color words printed in congruent ink color (the words purple, yellow, red, green, orange printed in the same color) and served as a measure of color naming speed in the absence of interference. Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity The color stroop card included 5 color words (purple, yellow, red, green and orange). It consisted of twenty lines, on each of which the 5 words comprising that card appeared. Therefore, each of the 5 words appeared 20 times for a total of 100 words. On each line, words and colors were randomized such that no word (or color) appeared twice on the same line, and no consecutive words (or ink color) were the same. Each line contained one word printed in black for the switch component. Furthermore, no same word-ink color combination appeared on two consecutive lines. Cards were printed using a professional quality printer on letter sized card stock paper using 17 point “Courier New” font. Three Emotional Stroop cards were included in the study: one for rejectionthreat, one for general negativity and one for neutral stimuli. However, because prior research shows that high RS people show attentional disruptions that are specific to processing rejection information and that are not observed for negative and neutral stimuli (Ayduk et al., 1999; Berenson et al., 2007), we focused on the rejection-threat Stroop data in the present study. Detailed description of the development and piloting of the stimuli used in the emotional Stroop cards can be found in Berenson, et al., 2007. The 5 rejection words included were “ignored,” “unwanted,” “rejected,” “disliked,” “shunned,” which were rated by pilot subjects as highly relevant to rejection and high in negativity. The Rejection Stroop card used the same 5 colors and the sequencing rules as the Color Stroop card described above. RSQ. The RSQ contains 18 items that depict hypothetical interpersonal interactions where rejection by a significant other is possible (e.g. “You ask your partner to move in with you”). For each situation, participants indicate their level of anxiety about the possibility of rejection, as well as the perceived likelihood (or the expectation) that the significant other depicted will respond with rejection. For each scenario, the expected likelihood of rejection is multiplied by the degree of anxiety and then these weighted scores are averaged across the 18 situations. In this study the mean RSQ score was 8.22 (SD = 2.53; = .85). Hostile conflict behavior. Participants were asked to recall the conflicts they had with their current romantic partner over the last year and rate the descriptiveness of a series of behaviors on a 1 (not at all descriptive) to 6 (extremely descriptive) scale. These items were loosely based on Straus (1974) to tap into psychological/verbal aggression and onto Rusbult’s Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity (Rusbult, 1993) construct of exit behavior: "insulted or swore at the other person," "blamed the other person," said something intended to hurt the other person’s feelings,” "stormed off," "threatened to leave the relationship.” Ratings were averaged ( = .83) to create a hostile conflict behavior composite (M = 2.48; SD = 1.18). Stroop interference scores. Preliminary analyses showed participants made very few errors in the Stroop tasks precluding any meaningful analysis using them as an index of performance. Therefore, the primary analyses reported below focus on response times. Because all trials on the baseline color-naming card were congruent (colors words and ink-color always matched), interference scores for color, and rejection Stroop cards were computed as residuals after regressing response times on each card on the baseline color-naming card. Interference times on the Color Stroop card operationalized cognitive inhibitory control with lower interference (i.e., faster response times), indicating higher cognitive inhibitory control. Interference times on the rejection Stroop card operationalized attentional capture by rejection threat with lower interference (i.e., faster response times) indicating lower vigilance. Results Does cognitive inhibitory control interact with RS in predicting attentional capture? To examine the moderation hypothesis, we performed a regression analysis on attentional capture by rejection threat (i.e., residualized reaction time scores on the rejection Stroop card) with RS, cognitive inhibitory control (i.e., residualized interference scores on the Color Stroop card) and their interaction as predictors. Predictors were centered on their mean and used as continuous variables. Consistent with our hypothesis, the results yielded a significant RS X cognitive control interaction F(3,36) = 4.44, p < .05. Figure 1 plots this interaction using unstandardized parameter estimates from this analysis. Simple slopes analyses (Aiken & West, 1991) conducted at 1 SD above and below the mean on each predictor indicated that among people low in cognitive inhibitory control, high RS people experienced more attentional capture by rejection threat than their low RS counterparts (β = .33, t(38)= 2.76, p < .05 ). In contrast, among those high in cognitive inhibitory control, Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity RS was not related to attentional capture by rejection threat (β = -.07, t(38) = -.42, ns). Furthermore, the protective effect of high cognitive inhibitory control (i.e., low interference, faster response times) against attentional capture by rejection threat was greater among high RS (β = .95, t(38) = 6.58, p < .05) than among low RS (β = .55, t(38) = 3.92, p < .05) participants. Attentional capture by rejection 15 10 5 High Cognitive Control Low Cognitive Control 0 -5 -10 Low RS High RS Figure 1. Attentional capture by rejection (i.e., response times for rejection threat words) as a function of Rejection Sensitivity (RS) and Cognitive inhibitory control. Notes. Greater the interference to rejection words (i.e., slower response times), greater the attentional capture. Greater the interference on the Color Stroop (i.e., slower response times), lower the cognitive inhibitory control. Attentional capture by rejection = .40 + .55 (RS) + .48 (Cognitive inhibitory control)* + .05(RS x Cognitive inhibitory control)*. *p < .05. Does cognitive inhibitory control interact with RS in predicting conflict hostility? Regression analysis also revealed the expected interaction between RS and cognitive inhibitory control on conflict hostility, F(3,36) = 8.61, p < .05. Figure 2 plots this interaction using unstandardized parameter estimates from this analysis. Simple slope analyses revealed that among participants low in cognitive inhibitory control, RS was positively, but not significantly related to more conflict hostility (β = .18, t(38)= 1.10, ns). Among people high in cognitive inhibitory control, RS was negatively related to conflict hostility (β Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity = -.60, t(38) = -2.43, p < .05). Furthermore, among high RS people high cognitive inhibitory control (low interference, faster response times) was related to less conflict hostility (β = .57, t(38) = 2.79, p < .05). Among low RS people, cognitive control was not systematically related to hostile behavior (β = -.21, t(38)= -1.08, ns). High Cognitive Control 3.5 Low Cognitive Control Hostile conflict behavior 3 2.5 2 1.5 Low RS High RS Figure 2. Hostile conflict behavior as a function of Rejection Sensitivity (RS) and Cognitive inhibitory control. Notes. Greater the interference on the Color Stroop (i.e., slower response times), lower the cognitive inhibitory control. Hostile conflict behavior = 2.57 + -.10 (RS) + .01 (Cognitive inhibitory control)* + .01 (RS x Cognitive inhibitory control)*. * p < .05. Discussion The goal of the present study was to examine whether cognitive inhibitory control – the ability to disengage from highly salient cues that interfere with completion of a central task, and inhibiting prepotent habitual responses – served as a protective factor against RS, a personality disposition that is associated with both personal and interpersonal difficulties. Using the cognitive Stroop paradigm to operationalize cognitive inhibitory control, we tested two hypotheses and found support for them. The first hypothesis was that cognitive inhibitory control would moderate high RS individuals' attentional capture by rejection threat. Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity Indeed, our findings indicated that whereas RS was positively related to attentional capture by rejection among participants with low cognitive control, this relationship was not significant among those high in cognitive inhibitory control. In other words, cognitive control served as a protective mechanism for high RS individuals, equating them to low RS people in their tendency to show automatic vigilance for rejection threat. Our second hypothesis was that cognitive inhibitory control would also moderate the direct relationship established in prior research between RS and hostility (e.g., Ayduk et al., 1999). In this sample, high RS was not significantly related to higher means levels of conflict hostility however (r = .05). One reason for this could be that people who get involved in relationships tend to be lower in RS (see Downey, Freitas et al., 1998) as the case in this study. Furthermore, in relationships where partners are still trying to secure each other’s commitment (as is typical in most college dating situations), high RS individuals may inhibit active forms of hostility to prevent rejection and secure acceptance (see Ayduk et al., 2003). Both of these factors may have attenuated the direct relationship between RS and negativity of behavior towards dating partners in the current sample. Nevertheless, in moderation analysis testing our second hypothesis, we found that high RS individuals high in cognitive inhibitory control were lower in conflict hostility in comparison to high RS people low in cognitive control. In fact, they reported lower hostility than even low RS individuals. Highly similar to this pattern, Ayduk et al. (2000, Study 2) reported that high RS middle school children with high delay of gratification ability tended to be lower in peer aggression than low RS children. Altogether, one interpretation of this overall pattern is that to the extent that high RS taps into greater motivation to establish and maintain close relationships, having the competencies that allow one to regulate their emotions in frustrating and aversive social interactions enhances high RS individuals’ ability to inhibit hostility towards partners more so than low RS participants, for whom relationship maintenance goals may not be as salient, or self-relevant. On the other hand, it is also possible that high RS people with self-regulatory competencies overcompensate for their vulnerability, for example, through over ingratiation (Romero-Canyas, Downey, Cavanaugh, & Pelayo, under review), which in the long-term may also create difficulties for the relationship and the self-concept of the individual. Clearly, this is an issue that will be important for future research to pursue. Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity As a whole, the present study yields evidence that cognitive inhibitory control may be a protective mechanism against the maladaptive processing dynamics of high RS. Availability of this controlled regulatory mechanism seems to alter the RS dynamic at the level of early-attentive automatic processing of rejection-related threat information suggesting interventions that target processes prior to encoding might be particularly instrumental in altering high RS individuals' maladaptive interpersonal behavior. However, this does not preclude the possibility that cognitive inhibitory control may also serve to break the link between RS and negative outcomes by directly acting on more controlled processes operating during response generation and response inhibition. Clearly, questions remain for future research, but the study starts to yield evidence for the possible buffering effects of cognitive inhibitory control against high RS. References Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Algom, D., Chajut, E., & Lev, S. (2004). A rational look at the emotional stroop phenomenon: A generic slowdown, not a stroop effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(3), 323-338. Arriaga, X. B., & Rusbult, C. E. (1998). Standing in my partner's shoes: Partner perspective taking and reactions to accommodative dilemmas. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(9), 927-948. Ayduk, O., Downey, G., & Kim, M. (2001). Rejection sensitivity and depressive symptoms in women. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 868-877. Ayduk, O., Downey, G., Testa, A., Yen, Y., & Shoda, Y. (1999). Does rejection elicit hostility in rejection sensitive women? Social Cognition.Special Issue: Social cognition and relationships, 17(2), 245-271. Ayduk, O., Gyurak, A. & Luerssen, A (in press). Individual differences in the rejection-aggression link in the hot sauce paradigm: The case of Rejection Sensitivity, Journal of experimental social psychology. Ayduk, O., Mendoza-Denton, R., Mischel, W., Downey, G., Peake, P. K., & Rodriguez, M. (2000). Regulating the interpersonal self: Strategic selfregulation for coping with rejection sensitivity. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 79(5), 776-792. Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity Ayduk, O., Zayas, V., Downey, G., Cole, A.B., Shoda, Y., & Mischel, W., (in press). Rejection Sensitivity and Executive Control: Joint predictors of Borderline Personality features, Journal of Research in Personality. Berenson, K., Gyurak, A., Ayduk, O., & Downey, G. (2007). Attentional bias in rejection sensitivity, Manuscript in preparation. Block, J. (2005). The stroop effect: Its relation to personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(3), 735-746. Cohen, J. D., Dunbar, K., & McClelland, J. L. (1990). On the control of automatic processes: A parallel distributed processing account of the stroop effect. Psychological review, 97(3), 332-361. Davis, M. (1992). The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 15, 353-375. Downey, G., & Feldman, S. I. (1996). Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 70(6), 13271343. Downey, G., Bonica, C., & Rincón, C. (1999). Rejection sensitivity and adolescent romantic relationships. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press. Downey, G., Feldman, S., Ayduk, O. (2000). Rejection sensitivity and male violence in romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 7, 45-61. Downey, G., Freitas, A. L., Michaelis, B., & Khouri, H. (1998). The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 75, 545-560. Downey, G., Khouri, H., & Feldman, S. I. (1997). Early interpersonal trauma and later adjustment: The mediational role of rejection sensitivity. Rochester, NY, US: University of Rochester Press. Downey, G., Lebolt, A., Rincón, C., & Freitas, A. L. (1998). Rejection sensitivity and children's interpersonal difficulties. Child development, 69(4), 1074-1091. Downey, G., Mougios, V., Ayduk, O., London, B. E., & Shoda, Y. (2004). Rejection sensitivity and the defensive motivational system: Insights from the startle response to rejection cues. Psychological Science, 15(10), 668-673. Eigsti, I., Zayas, V., Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., Ayduk, O., Dadlani, M. B., et al. (2006). Predicting cognitive control from preschool to late adolescence and young adulthood. Psychological Science, 17(6), 478-484. Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511-524. Horney, K. (1994). The neurotic personality of our time. New York, NY, US: W. W. Norton & Co. Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (1990). Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychological review, 97(3), 377-395. Metcalfe, J., & Mischel, W. (1999). A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological review, 106(1), 3-19. Mischel, W., & Ayduk, O. (2004). Willpower in a cognitive-affective processing system: The dynamics of delay of gratification. In R. F. (. Baumeister, & K. D. (. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 99-129). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. L. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933-938. Pietrzak, J., Downey, G., & Ayduk, O. (2005). Rejection sensitivity as an interpersonal vulnerability. In M. Baldwin (Ed.), Interpersonal cognition (pp. 62–84). New York: Guilford Press. Posner, M. I., & Rothbart, M. K. (2000). Developing mechanisms of selfregulation. Development and Psychopathology.Special Issue: Reflecting on the past and planning for the future of developmental psychopathology, 12(3), 427441. Romero-Canyas, R., Downey, G., Cavanaugh, T. J., & Pelayo, R. (under review). When rejection leads to ingratiation: Rejection Sensitivity and efforts to ingratiate. Manuscript submitted for publication. Rusbult, C. E. (1993). Understanding responses to dissatisfaction in close relationships: The exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect model. In S. Worchel & J. A. Simpson (Eds.), Conflict between people and groups: Causes, processes, and resolutions (pp. 30-59). Chicago: Nelson-Hall. Straus, M. A. (1974). Leveling, civility, and violence in the family. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 36, 13-29. Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial-verbal reaction. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18, 643–662. Williams, J. M., Mathews, A., & MacLeod, C. (1996). The emotional stroop task and psychopathology. Psychological bulletin, 120(1), 3-24. Cognitive inhibitory control and Rejection Sensitivity Wylie, G., & Allport, A. (2000). Task switching and the measurement of "switch costs". Psychological research, 63(3-4), 212-233. Yovetich, N. A., & Rusbult, C. E. (1994). Accommodative behavior in close relationships: Exploring transformation of motivation. Journal of experimental social psychology, 30(2), 138-164. Author Note Özlem Ayduk, Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley; Anett Gyurak, Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley. This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH0697043). We would like to thank Serena Chen, Geraldine Downey, John Kihlstrom, Ethan Kross, and Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton for their helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript, and Natalie Castriotta for her help in data collection. Address correspondence to Özlem Ayduk (ayduk@berkeley.edu), 3210 Tolman Hall, Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720.