HYT-TTP Level One and 200-Hour Program Retreat Handouts

The Mechanics of Breathing

Muscles of inspiration

The Diaphragm

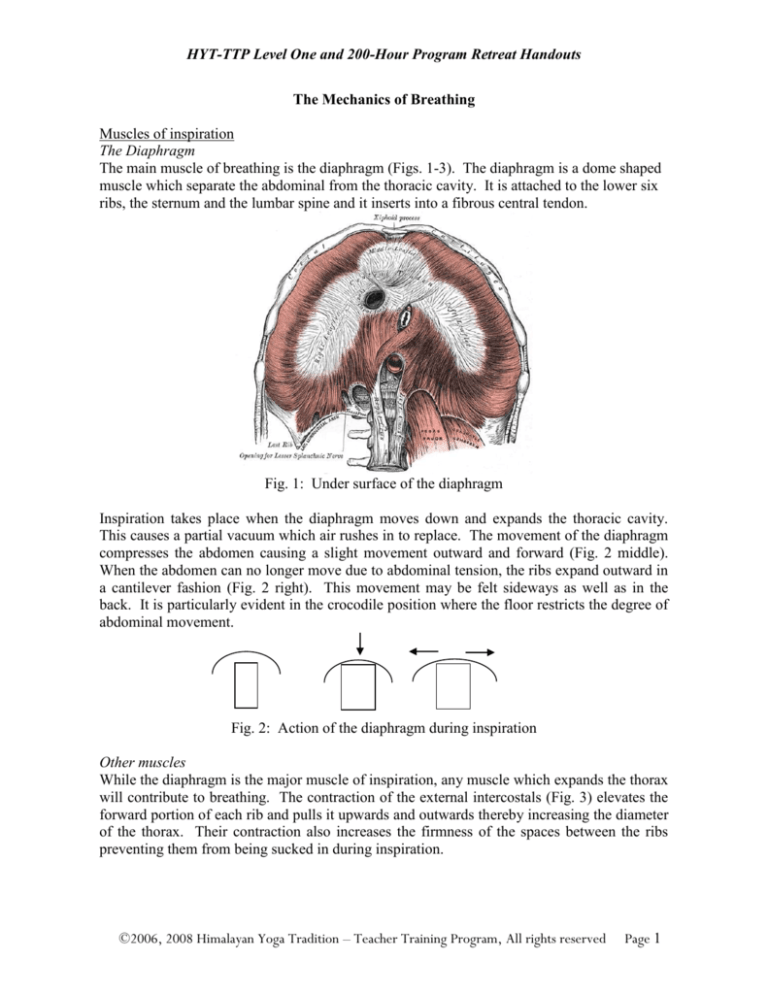

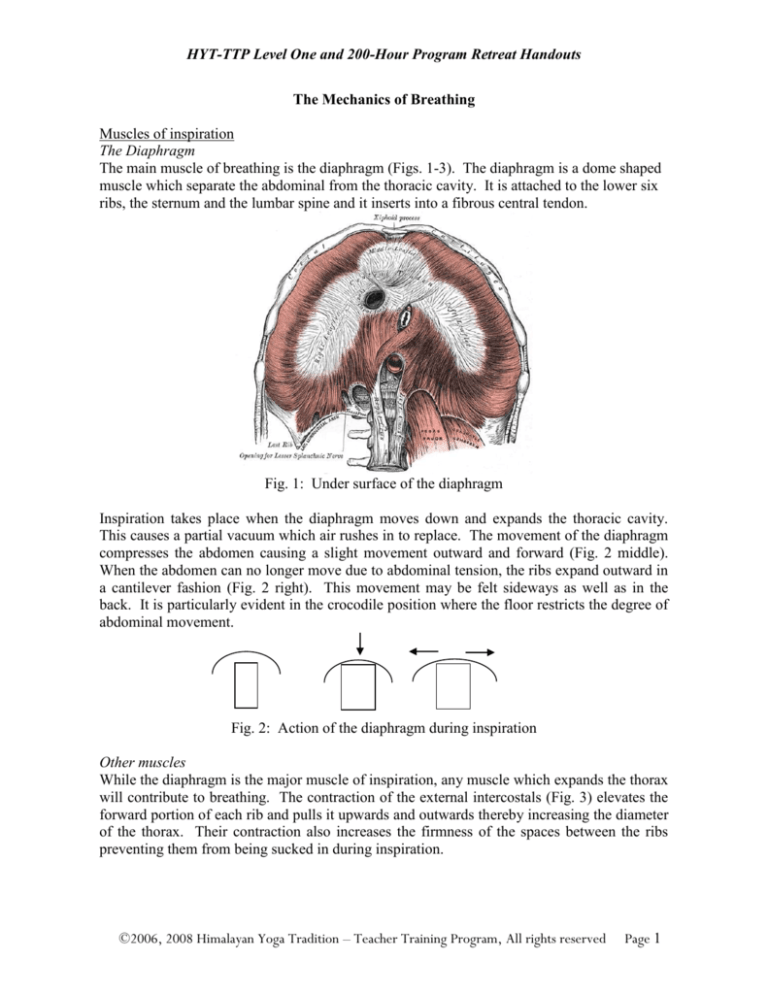

The main muscle of breathing is the diaphragm (Figs. 1-3). The diaphragm is a dome shaped

muscle which separate the abdominal from the thoracic cavity. It is attached to the lower six

ribs, the sternum and the lumbar spine and it inserts into a fibrous central tendon.

Fig. 1: Under surface of the diaphragm

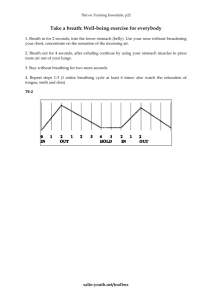

Inspiration takes place when the diaphragm moves down and expands the thoracic cavity.

This causes a partial vacuum which air rushes in to replace. The movement of the diaphragm

compresses the abdomen causing a slight movement outward and forward (Fig. 2 middle).

When the abdomen can no longer move due to abdominal tension, the ribs expand outward in

a cantilever fashion (Fig. 2 right). This movement may be felt sideways as well as in the

back. It is particularly evident in the crocodile position where the floor restricts the degree of

abdominal movement.

Fig. 2: Action of the diaphragm during inspiration

Other muscles

While the diaphragm is the major muscle of inspiration, any muscle which expands the thorax

will contribute to breathing. The contraction of the external intercostals (Fig. 3) elevates the

forward portion of each rib and pulls it upwards and outwards thereby increasing the diameter

of the thorax. Their contraction also increases the firmness of the spaces between the ribs

preventing them from being sucked in during inspiration.

©2006, 2008 Himalayan Yoga Tradition – Teacher Training Program, All rights reserved

Page 1

HYT-TTP Level One and 200-Hour Program Retreat Handouts

Fig. 3: External (left) and internal (right) intercostal muscles

In addition to the diaphragm and external intercostals, the scalenus and sternocleidomastoid

muscles (Fig. 4) help to lift the sternum and upper rib cage thereby expanding the thorax from

the top. They are inactive during quiet breathing but become important during heavy exercise

(e.g. running).

Fig. 4: Scalenus and sternocliedomastoid muscles

Muscles of expiration

While the process of inspiration requires muscular contraction and is therefore “active”, the

process of expiration is in theory “passive”. As inspiration proceeds and expands the thorax it

stores potential energy in the elastic tissue of the rib cage similar to the process of stretching a

©2006, 2008 Himalayan Yoga Tradition – Teacher Training Program, All rights reserved

Page 2

HYT-TTP Level One and 200-Hour Program Retreat Handouts

spring. When the tension is released at the end of inspiration this potential energy is also

released causing the size of the thorax to return to normal. Your last breath before you die

will always be an exhalation!

The release of tension is generally not abrupt or sudden. Consequently the diaphragm may be

considered an accessory muscle of expiration since its tension is released gradually. The

other accessory muscles of expiration are the abdominal muscles (Fig. 5) and the internal

intercostals (Fig. 3). The abdominal muscles mainly come into play during higher respiration

rates (> 40 liters/minute), larger tidal volumes or active breathing exercises such as

kapalabhati. The internal intercostals muscles are the antagonists of the external intercostals.

They depress the ribs moving them downwards and inwards. They also stiffen the spaces

between the ribs so they do not bulge outwards during expiration.

Fig. 5: The Transversus abdominis, Rectus abdominis, and Pyramidalis

Putting it all together

Breathing can be characterized mechanically in terms of (1) rate, (2) depth (i.e. tidal volume),

(3) the ratio of the inhalation time to exhalation time (I:E ratio), (4) smoothness, (5) locus of

the breath and (6) utilization of the mouth or nose. A yogic breathing pattern suitable for

meditation will have a slow rate, large tidal volume, longer exhalation than inhalation,

be smooth, primarily use the diaphragm and lower external intercostal muscles and be

nasal. Some commentary on this statement is necessary.

An individual’s metabolism will generally determine the amount of air per minute (minute

ventilation) which is required during normal breathing. This can be achieved either by fast

shallow breaths or longer deeper breaths. In yoga, longer deeper breaths are preferred with a

longer exhalation than inhalation. This appears to decrease the degree of sympathetic

activation (i.e. the flight or fight response) and as the relaxation response proceeds the

metabolism itself actually slows down allowing the minute ventilation to decrease.

©2006, 2008 Himalayan Yoga Tradition – Teacher Training Program, All rights reserved

Page 3

HYT-TTP Level One and 200-Hour Program Retreat Handouts

Furthermore, slower, deeper breaths appear to be more efficient in terms of gas exchange

even though the mechanical energy required to achieve this form of breathing is often greater.

The locus of the breath is the abdomen and mid thorax. Classically in a yoga class one would

hear admonitions against “thoracic breathing” and abdominal breathing would be suggested as

an alternative. This is probably something of an oversimplification. Coulter1 identifies 5

patterns of breathing: constricted thoracic, empowered thoracic, abdomino-diaphragmatic

(“abdominal”), thoraco-diaphragmatic (“diaphragmatic”), and paradoxical breathing. The

distinction between “abdominal” and “diaphragmatic” breathing patterns is not made in all

yoga books2 but is discussed in detail in others3. Both patterns obviously involve the

diaphragm but in thoraco-diaphragmatic the abdominal muscles maintain a certain tonus or

tension during inhalation whereas in abdomino-diaphragmatic it is absent. This tonus arises

in part to a straight spine which stretches the abdominals and partly as a result of maintaining

control to “smooth” the breath. It is not so much that the abdomen is completely constricted

(as in constricted thoracic breathing) but enough so that there is some cantilever action (Fig. 2

right) as part of the breath cycle. It should be mentioned that there is also a thoracic

component to thoraco-diaphragmatic breathing as well. This arises as a result of the need to

increase tidal volume in response to the decrease in breath rate. Thus this type of breath

pattern is not purely abdominal. It is sometimes called the “complete breath4” in yogic texts.

In teaching diaphragmatic breathing to a beginning class some of these distinctions may be

overly subtle. Simply pointing out the difference between an abdominal and thoracic breath

pattern and focussing on relaxing and deepening the breath may be sufficient. Also using

words such as “control” or “tension” sometimes disturbs the breathing process. The concept

of “passive volition” which was introduced in biofeedback training may actually be more

germane breath re-education. The individual mentally requests a change in the breathing

process and then observes this change as a witness or passive observer. As this habit becomes

more ingrained, additional observations or details can be added from the details mentioned

above.

1

H. David Coulter. Anatomy of Hatha Yoga. Honesdale, PA: Body and Breath, 2001.

See for example S Rama, R Ballentine, A Hymes. Science of Breath. Honesdale, PA: Himalayan Institute,

1979.

3

Andre van Lysebeth. Pranayama: The Yoga of Breathing. London: Unwin Paperbacks, 1979.

4

This is something of a misnomer since it doesn’t include the clavicular component of the breath which would

involve moving the shoulders.

2

©2006, 2008 Himalayan Yoga Tradition – Teacher Training Program, All rights reserved

Page 4