Thomas More was a scholar, statesmen and Saint

advertisement

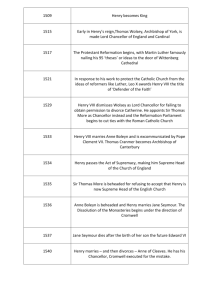

Annual Thomas More Address at St. Dunstan’s Church, Canterbury 6 July 2007 Thomas More was a scholar, statesmen and saint. His life has attracted so many superlative assessments… most of them positive but some bitterly against… that it is easy to lose sight of the human figure. He was born in 1478 to a comfortable middle-class family -- his lawyer father … John More… went on to be a minor judge. He was picked out early as a bright child at the age of 12 and sent as a page to the household of John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor. From there he went briefly to Oxford, and then to train as a lawyer at New Inn. He toyed with the idea of holy orders… keeping friendships in the Charter House community all his life… but made his career as a lawyer. He became successful in his chosen profession, establishing a reputation for brilliance, determination… and honesty. At the age of 27, he married Jane Colt by whom he had three daughters and a son but their happy married life was devastated by her death six years later, the year after he was elected to Parliament. He quickly found a widow, seven years his senior, the redoubtable Mistress Alice, to provide a mother for his children. Contemporary accounts describe his household as a warm and happy one. Devoted 1 to his children, we are told that More used to join in family singsongs despite having a rotten singing voice. Accounts of his dealings with the ambitious Mistress Alice make touching reading. Alice "What will you do since you do not wish to put yourself off as other folk do? “Would God, I were a man - look what I would do." Thomas "Why wife what would you do?" Alice "What? By God, go forward with the best! Because as my mother liked to say it is always better to rule than to be ruled. And therefore by God I would never be so foolish as to be ruled when I might rule." Thomas “Here I must say you have said the truth, because I've never yet found you willing to be ruled.” More first reached the public notice as under-Sheriff of London… effectively legal adviser to the Mayor… when the notorious Mayday riot took place in 1517, causing a conflagration in which hundreds of houses were destroyed. In the Elizabethan play of Thomas More, co-authored by Shakespeare, there is a gripping account of More first confronting and facing down the rioters and then persuading King Henry not to execute them. Suppressed by the Elizabethan censors, the play has recently been revived by the Royal Shakespeare Company. 2 In the meantime his law practice had blossomed and he was enjoying prosperity. A year later he took the fateful step of joining the King's service as a member of the king's council, no doubt to the delight of Mistress Alice. Fatefully it was just a few months after Martin Luther had nailed his 95 theses to the door of the Castle Church at Wittenberg. Thomas became intimate with the king showing a flair for diplomacy and playing an important role in peace negotiations, including the famous Field of the Cloth of Gold summit with King Francis. Indeed, More became so popular with the king and queen that they used to call him to dine with them every night, preventing him from getting home to his wife and children. With his characteristic combination of tact and determination… we are told he gradually changed his manner until they ceased to call for him so often. In 1521 More became Speaker of the Commons. Previous speakers had been executed for resisting the King. A mural visitors pass, on the way into Parliament, depicts Thomas facing down the King's man, Lord Chancellor Wolsey, who was demanding new taxation without debate. In parallel with his rise in public life, More established a reputation in the scholastic and literary worlds. His book on Richard III, a stark portrait of that tyrant, formed the basis for one of 3 Shakespeare's first plays. His output of poems, many of them humourous… and some pointing to abuses in the Church… was prodigious. Indeed when Dr Johnson came to compose his History of the English language, centuries later, he devoted twice as much space to More’s poetry as to that of Chaucer. Assisting Henry with his literary efforts, Thomas persuaded him not to write anything conceding secular power to the pope, emphasising the split between religious and secular authority. More and his close friend Erasmus formed the core of a group known as humanists… no connection with the modern movement of that name… with their commitment to the study of Greek, and the extension of education. He ensured that his daughters received a full education, something inconceivable a generation earlier. His early instinct was one of tolerance. As well as speaking out against clerical abuses, he joined the calls for a translation of the Bible into English, the only major language in which there was no vernacular version, and showed tolerance towards those pressing for other reforms. In 1525 events took place which completely changed his outlook. In Germany, the so-called Peasant’s Revolt took place. Hundreds of thousands of peasants, many of them supporters of Luther's and carrying banners bearing his slogans, rose up in protest at serfdom and their treatment by their masters. Yet they were brutally suppressed by their lords, egged on by Luther’s inflammatory sermons: " Stamp, smite and slay all you can...you 4 cannot meet a rebel with reason.” Some 70,000… largely unarmed… protesters were slaughtered. More began a bitter exchange with Luther, combining obscene insults with theological arguments on both sides, while Erasmus … generally regarded as a moderate figure… also called for the military suppression of Luther. It was into this explosive atmosphere that Luther's English ally William Tyndale published two books, one a translation of the Bible, the other entitled The obedience of a Christian man. Tyndale was a brave man. But in his implacable hatred of the Catholic Church was, in the eyes of Thomas More, determined to throw the baby of traditional Christian order out with the bath water of clerical abuses. Tyndale taught that the king was above the law "The King is in this world, without Law and may at his lust do right and wrong… The king is in the place of God, and his law is God’s law." At any time, this doctrine would have been obnoxious to Thomas More... with his fervent belief in the Rule of Law but this was not just any time. Central Europe was in ferment. King Henry was pursuing a bloody and unnecessary war against France while the whole continent faced a threat from the Turks, who were overrunning Southeast Europe. Were he with us today, I believe, that More would argue that he faced the same dilemma as today’s government in Britain faces in dealing with inflammatory preachers in mosques. The liberal 5 tendencies of his youth were cast aside as he became determined that the chaos and bloodshed on the Continent should not be repeated here. In 1529, Thomas was appointed Lord Chancellor of England, head of the judiciary and head of Henry's government. In two years he cleared a seven-year backlog of cases further establishing his reputation for integrity. Yet, from the time of his appointment, More was already under pressure. He had helped to negotiate a peace with France but the king's application for a divorce was as obnoxious to him as it was to the church and by 1530 Henry was taking the first steps towards a breach with Rome. While More battled against, the destruction of the traditional order, as Lord Chancellor, he supported the arrest and burning of five Protestant preachers. They were saintly men who, as the situation became more desperate, he saw… unfairly to us in retrospect… as ringleaders in the descent into barbarism. Less surprisingly he encouraged Charles V to arrest and eventually execute Tyndale, who had fled to the continent. Tyndale… it should be recorded… died bravely a year after More. The Emperor Charles V secretly wrote to the embattled Lord Chancellor inviting him to flee Britain and take the reins as first Minister of Europe's mediaeval superpower, the Holy Roman 6 Empire. More refused, determined to stay and die at his post… or rather not at his post. Unwilling to take the oath of supremacy, recognizing the king as head of the Church, he resigned in 1532. Two years later, he was arrested and cast into the Tower of London. Beyond its walls, the first steps began towards the dissolution of the monasteries which provided the welfare of the era… the almshouses, the hospitals and many schools. The monasteries were seized, the almshouses closed and London’s four hospitals emptied, leaving a miserable vacuum. This was eventually to be filled by Henry's successors, with the launch of the King Edward Schools, and the Elizabethan Poor Law. Those who resisted were faced with prison and execution. The gainers of course were not only the King but a large… literally nouveau riche… class who picked up the assets at knockdown prices. As Disraeli was to point out 300 years later they then firmly kicked away the ladders and social mobility stopped until Victorian times. Meanwhile religious terror gripped the formally quiet England. Henry burnt dozens of Protestants to prove his orthodoxy, while executing those loyal to the Pope - and latterly the monasteries - for treason. Yet, in the Tower, Thomas wrote some of his most brilliant works. He reverted, at least in part, to his original moderation, arguing that... in the face of the Turkish threat… Catholics must debate with Protestants and recognize common ground where it existed… 7 without giving way on essentials like the nature of the Eucharist. He reminded us that we must obey the Law except when it absolutely contravenes God's Law… Earlier this year a Bill in Parliament required Christian adoption organisations to proclaim that marriage and homosexual unions were to be treated equally for adopting children.. Those that refused, including the Catholic Children's Society and at least one evangelical fostering group will have to close their doors at the end of next year unless there is a last-minute reprieve. Today, Christians face wider challenges. There is a steady pattern of ideas starting as government guidance for schools, then a few years later being turned into Law. Yet much of today’s school guidance is deeply hostile to Christian principles… for example, teaching children that sex before marriage is wrong – rather than a lifestyle choice is forbidden. Twenty First Century England presents Christians with some serious challenges. But not like the Sixteenth. More was confined without warm clothing or bedding and appears to have caught pneumonia. He turned his back on fame and fortune and the pleadings of his loving family. Mistress Alice was incredulous. At his trial, the next year, he was exhausted and his voice was barely audible yet he demolished his accusers, with devastating effect. For all this time, he had remained silent on the issue of the Act of Supremacy while Henry’s men tried a series of tricks to get him to speak. One incident at the trial illustrates the standing Thomas enjoyed. 8 Richard Rich had been sent to question him and, while their discussion was going on, an under warden and a workman had entered the cell to remove Thomas More’s books. These men must have realised how richly they would be rewarded, if they testified against More, and the danger they exposed themselves and their families to by not doing so. Yet, questioned at the trial, the under warden insisted that he had heard nothing and the carpenter, a sturdy English workman, said that the learned talk was all way above his head. More was accused of a number of ancillary charges, including torturing suspects, something he vehemently denied. As he gave his life rather than take an oath dishonestly, we must take him at his word. He was sent back to the Tower, condemned to be agonisingly hanged drawn and quartered, a sentence reduced to beheading in a small act of mercy by Henry on the morning of his death a few later. To try to frighten Thomas into recantation Cromwell arranged for four monks including the Abbot of the Charter House to be sent past his window on the way to their execution by hanging drawing and quartering. In fact their courageous bearing strengthened his resolve. Still weak from pneumonia he walked to his execution in the company of his old friend the Lieutenant of the Tower, who burst 9 into tears as they came into view of the execution block. More patted him on the shoulder and said, “Be of good cheer, Master Lieutenant. You will have to give me your arm on the way up; I'll shift for myself on the way down.” Henry had ordered him to be brief in his final speech. He was. "Tell the King that I die his loyal servant but God's servant first." That famous Anglican clergyman Dean Jonathan Swift famously remarked that Thomas More was the greatest figure of the modern era, the only one to compare to the great men of the ancient world. And he started the national self-portrait of the charming Englishman who goes to his death with a smile on his lips. 10