Rapid Responses published

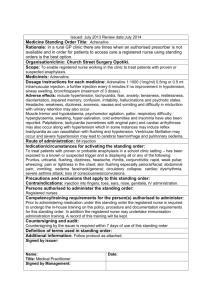

advertisement

Rapid Responses published: Algorithm illogical Yoav Ben-Shlomo (5 December 2003) Adrenaline in anaphylaxis G Sivagnanam (5 December 2003) need for a more refined working definiton Asif Raheem (7 December 2003) Identifying people most at risk of severe anaphylaxis, and provision of adrenaline autoinjectors. Simon G. A. Brown (9 December 2003) Successful use of pure alpha agonists in epinephrine resistant anaphylaxis Michael E McBrien, Dara S Breslin (10 December 2003) Authors response Andrew P C McLean-Tooke, Claire A Bethune, Gavin P Spickett (10 December 2003) A clear link between adrenaline intravenous administration and severe cardiovascular effects Sergio Abanades, Joan Buch. Clinical Hematology Resident. Hospital del Mar (11 December 2003) Observation after adrenaline: what is the evidence? Martin F Wiese, Catherine Johnson, senior house officer and John A. Henry, professor (11 December 2003) Subcutaneous adrenaline for anaphylaxis: compromise in high risk patient with mild symptoms Michal R Pijak, Frantisek Gazdik, Katarina Gazdikova (19 December 2003) Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the risk and benefit? Michal R Pijak, Frantisek Gazdik, Katarina Gazdikova (21 December 2003) Does adrenaline have an important drug interaction with alpha adrenergic receptor blocking drugs? Alan Watson (22 December 2003) Algorithm illogical Yoav Ben-Shlomo, Senior Lecturer in Clinical Epidemiology Dept. of Social Medicine, University of Bristol Send response to journal: Re: Algorithm illogical 5 December 2003 The review of adrenaline for anaphylaxis by McLean-Tooke and colleagues is a most helpful piece of work. However, their recommended algorithm (fig 3) for identifying patients that may benefit from an adrenaline auto-injector seemed to be inconsistent with their own review of the evidence. Whilst there is clearly limited epidemiological evidence, they state that (1) the severity of a past reaction does not predict a future reaction. Hence a child with an urticarial response to nuts may on subsequent challenge have a life threatening response. (2) Asthma co-morbidity appears to increase the risk of a fatal reaction. However, their suggested algorithm ignores the presence/absence of asthma unless you have had a severe reaction and recommends that asthmatic children with only a local reaction not be provided with an auto-injector even though they are candidates for a future life threatening reaction. It also ignores other factors such as accessibility to emergency room facilities e.g. a child who lives in a rural area is clearly at greater risk of death without an Epipen as it will take more time for an ambulance to arrive. Given the modest cost of an Epipen and its relative safety, this makes little sense to me. How can this be justified? I would welcome their comments. Competing interests: None declared Adrenaline in anaphylaxis G Sivagnanam, Additional Professor of Pharmacology Chengalpattu Medical College, Chengalpattu 603 001 Tamilnadu, India Send response to journal: Re: Adrenaline in anaphylaxis 5 December 2003 The following few points are in connection to the article entitled “Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence? 1 What is the best route for administering adrenaline? It is pertinent to note that for the following reasons adrenaline serves better if it is given by intramuscular rather than subcutaneous route. a. Absorption of epinephrine after subcutaneous injection is slow due to local vasoconstrictor action2. (However the same source indicates that adrenaline be given subcutaneously or intravenously with due caution for management of acute hypersensitivity). b. In general the rate of absorption of a drug by subcutaneous route is slower than that of intramuscular route. Upon sympathetic stimulation (as in shock) blood vessels supplying skeletal muscles bearing ?2 receptors dilate. The same effect can be expected with exogenously administered adrenaline and this is only partly counterbalanced by the vasoconstrictor action on the ? receptors that are also present in the vascular bed2. c. In shock there is already intense compensatory vasoconstriction in the skin hence absorption of drugs administered by subcutaneous route is slow and erratic. All these boils down to the fact that intramuscular route is best (or cautious intravenous) rather than subcutaneous. Does adrenaline have any important drug interactions? “Cocaine sensitises the heart to catecholamines (as does uncontrolled hyperthyroidism), and adrenaline is therefore relatively contraindicated (grade C)”1 However no alternative for such cases has been advocated by the authors. Whatever may be the coexisting factor, in a case of anaphylactic shock, theoretically speaking there seems to be no better alternative (physiological antagonist) than adrenaline (may be with half the dose as mentioned for patients on drugs like beta blockers, tricyclic antidepressants etc.). 1. McLean-Tooke APC, Bethune CA, Fay AC, Spickett GP. Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence? BMJ 2003; 327:1332–5 2. Hoffman BB In: Goodman & Gilman’s The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 10th Ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2001. pp 215-268 Competing interests: None declared need for a more refined working definiton Asif Raheem, emergency physician Abha genreal hospital, abha saudi arabia Send response to journal: Re: need for a more refined working definiton 7 December 2003 Sir, The clinical review ADRENALINE IN THE TREATMENT OF ANAPHYLAXIS was excellent, but for the working definition of anaphylaxis mentioned therein. A good working definition is that an anaphylactic reaction involves one or both of the two severe features: respiratory difficulty (which may be due to laryngeal oedema or asthma) and hypotension (which may present as fainting, collapse, or loss of consciousness). Very commonly in clinical practice we come across patients more often females fainting after a painful prick, usually due to pain, precipitating a vaso- vagal episode with blood pressure measurements < 90/60 mm of hg. Applying the above mentioned working definition all these syncopes also will come into the purview of anaphylaxis. Thus, a review of this working definition is required in near future. Asif RAHEEM.MD Emergency physician Abha general hospital. Abha Saudi Arabia. Competing interests: None declared Identifying people most at risk of severe anaphylaxis, and provision of adrenaline autoinjectors. Simon G. A. Brown, Consultant Emergency Physician and Senior Clinical Lecturer Fremantle Hospital and University of Western Australia, Fremantle, WA 6160, Australia Send response to journal: Re: Identifying people most at risk of severe anaphylaxis, and provision of adrenaline autoinjectors. 9 December 2003 In their review of adrenaline for the treatment of anaphylaxis, McLeanTooke and colleagues state that "the severity of previous reactions does not determine the severity of future reactions" [1]. In the setting of insect venom anaphylaxis, this is incorrect. A large prospective study of venom allergic individuals found no person went on to experience a reaction more severe than the worst prior reaction [2]. Another large sting challenge study and our prospective study of accidental field stings had similar findings, although a few individuals went on to experience more severe reactions [3,4]. Older age also predicts a higher risk of a Mueller grade IV (hypotensive) reaction [4]. Inaccurate patient recollection, incomplete medical records, fluctuations in sensitivity, and variation in the amount of venom delivered probably explain our observation that people with a history of Mueller grade III (respiratory) reactions frequently go on to experience a Grade IV reaction [5]. Therefore it is common practice to focus the provision of venom immunotherapy (VIT) and adrenaline autoinjectors (Epipens) on people with a history of respiratory or hypotensive reactions. However, because people with a history of milder reactions occasionally go on to experience a more severe reaction, VIT and/or Epipens should probably be offered if a person is frequently exposed in areas that are isolated with limited access to emergency medical care, even if they have history of only mild reactions. It is often not appreciated that adrenaline must be injected into the anterior thigh to achieve maximum absorption- injection into arm muscles is no better than the subcutaneous route [6]. It is good to see the recommendation the provision of two Epipens. In our sting challenge study, the median total dose of adrenaline (administered by intravenous infusion titrated to the lowest effective rate) was 762 mcg in patients experiencing hypotensive reactions, more than double the standard Epipen dose, and several required substantially more [7]. These results emphasise the importance of patients being instructed to: (1) not hesitate injecting themselves with adrenaline into the anterior thigh; (2) immediately call for ambulance assistance using the national emergency telephone number, and (3) use their second Epipen if they do not improve or continue to deteriorate. In a severe reaction, an Epipen simply "borrows time" until help arrives. REFERENCES 1. McLean-Tooke APC, Bethune CA, Fay AC, Spickett GP. Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence? BMJ 2003;327(7427):1332-1335. 2. van der Linden PW, Hack CE, Struyvenberg A, van der Zwan JK. Insect-sting challenge in 324 subjects with a previous anaphylactic reaction: current criteria for insect-venom hypersensitivity do not predict the occurrence and the severity of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1994;94(2 Pt 1):151-9. 3. Blaauw, P.J., O.L. Smithuis, and A.R. Elbers, The value of an inhospital insect sting challenge as a criterion for application or omission of venom immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 1996. 98(1): p. 3947. 4. Brown SGA, Franks RW, Baldo BA, Heddle RJ. Prevalence, severity, and natural history of jack jumper ant venom allergy in Tasmania. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111(1):187-92. 5. Brown SGA, Wiese MD, Blackman KE, Heddle RJ. Ant venom immunotherapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Lancet 2003;361(9362):1001-6. 6. Simons FE, Gu X, Simons KJ. Epinephrine absorption in adults: intramuscular versus subcutaneous injection. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108(5):871-3. 7. Brown SGA, Blackman KE, Stenlake V, Heddle RJ. Insect sting anaphylaxis; prospective evaluation of treatment with intravenous adrenaline and volume resuscitation. Emerg Med J 2004;(In Press). Competing interests: None declared Successful use of pure alpha agonists in epinephrine resistant anaphylaxis Michael E McBrien, Consultant Anaesthetist Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast BT12 6BA, Dara S Breslin Send response to journal: Re: Successful use of pure alpha agonists in 10 December 2003 We read with interest the excellent review by McLean-Tooke et al on adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis [1] and we would like to add our experience. This review, along with 2 other recent publications [2,3], failed to recommend the use of a pure alpha agonist in severe anaphylactic reactions unresponsive to epinephrine. The successful use of this treatment was described in a series of case reports by ourselves in 2001 [4] and by Higgins and Gayatri in 1999 [5]. There is no doubt that repeated administration of intramuscular epinephrine resistant anaphylaxis epinephrine is the treatment indicated for life threatening out of hospital anaphylaxis, as discussed by McLean-Tooke et al [1]. However, the in-hospital management of severe anaphylaxis which results in cardiac arrest, especially under anaesthesia, includes the use of intravenous epinephrine at 1:10,000 dilution as a first line treatment. Anaphylaxis under anaesthesia has been reported with an incidence of 1:13,000 [6] and between 1:10,000 to 1:20,000 [7] anaesthetics administered. Although this is uncommon, our hospital, with around 30,000 anaesthetic episodes per year, may see 2 or 3 severe cases annually. Our experience is that epinephrine resistant anaphylaxis does occur with electomechanical dissociation persisting despite the repeated administration of epinephrine in 1mg boluses. Severe anaphylaxis under anaesthesia probably represents the extreme edge of the spectrum of anaphylactic reactions, perhaps due to the concomitant administration of many drugs and the exposure of patients to rapid boluses of intravenous antigens. The severity of the reactions is reflected in the profound reduction in systemic vascular resistance that occurs due to the release of histamine and other vasoactive substances associated with mast cell degranulation and may lead to cardiac arrest secondary to electromechanical dissociation. Epinephrine has agonist activity at both alpha 1 receptors, causing vasoconstriction, and beta 1 receptors, causing increased inotropy and chronotropy of the heart. However, stimulation of beta 2 receptors in the smooth muscle wall of blood vessels in skeletal muscle and the liver causes these vessels to dilate. In normal subjects, it has been shown that an intravenous infusion of epinephrine may lead to a reduction in total peripheral resistance via this effect on beta 2 receptors [8]. In contrast, pure alpha 1 agonists, such as phenylephrine, produce unopposed vasoconstriction in peripheral vessels leading to an increase in peripheral vascular resistance. The primary effect of adrenaline during cardiopulmonary arrest is thought to be systemic vasoconstriction, due to alpha 1 receptor stimulation, elevating aortic diastolic pressure and thus increasing coronary perfusion pressure [9, 10]. One possible reason for a lack of response to epinephrine in cases of electromechanical dissociation secondary to reduced systemic vascular resistance may be that the drug’s effects on alpha 1 receptors (vasoconstriction) and beta 2 receptors (vasodilatation) do not correct the imbalance. A net effect of vasodilatation may persist no matter how much epinephrine is administered. In contrast, the vasoconstriction produced by pure alpha 1 agonists may lead to a more predictable increase in systemic vascular resistance in circumstances where excessive systemic vasodilatation already exists. Compensation for a profound falls in systemic vascular resistance may also be achieved by the administration of intravenous fluids, as described by Waldhausen et al [11], when epinephrine does not produce sustained cardiovascular improvement The risk of fatal cardiac arrythmias and myocardial infarction following the administration of intravenous epinephrine, as discussed by McLean-Tooke [1], are related to the beta 1 effects of the drug. Repeated boluses of epinephrine in pursuit of vasoconstriction in anaphylactic shock makes such adverse events more likely. However, by switching to pure alpha agonists in the treatment of epinephrine resistant cardiovascular collapse associated with anaphylaxis, the progression to such cardiac irritability, associated arrythmias and myocardial ischaemia may be avoided. The case reports by ourselves [4] and Higgins and Gayatri [5] would suggest that resuscitation from a suspected anaphylactic reaction should not be discontinued without the administration of a significant intravenous bolus of a pure alpha agonist following repeated intravenous boluses of epinephrine. Higgins and Gayatri proposed that the use of a pure alpha agonist should be considered before resorting to a third 1mg dose of epinephrine [5]. We would endorse this recommendation and encourage its adoption into future recommendations for the treatment of severe anaphylactic reactions. References: 1. McLean-Tooke APC, Bethune CA, Fay AC, Spickett GP. Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence? BMJ 2003;327:1332-35. 2. Hepner DL, Castells MC. Anaphylaxis during the perioperative period. Anesth Analg 2003;97:1381-95. 3. Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Suspected anaphylactic reactions associated with anaesthesia. London : Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2003. 4. McBrien ME, Breslin DS, Atkinson S, Johnston JR. Use of methoxamine in the resuscitation of epinephrine-resistant electromechanical dissociation. Anaesthesia 2001;56:1085-89. 5. Higgins DJ, Gayatri P. Methoxamine in the management of severe anaphylaxis. Anaesthesia 1999;54:1126. 6. Laxenaire MC. Epidemiological survey of anaphylactoid reactions occurring during anaesthesia. Fourth French multicentre survey (July 1994 -December 1996). Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 1999;18:796-809. 7. Fisher MM, Baldo BA. Anaphylaxis during anaesthesia; current aspects of diagnosis and prevention. Eur J Anaesthesiol 1994;11:26384. 8. Ganong WF. The Adrenal Medulla and Adrenal Cortex. In: Ganong WF ed. Review of Medical Physiology. London: Prentice-Hall International, 1989;301-24. adrenergic and 9 Yakaitis RW, Otto CW, Blitt CD. Relative importance of receptors during resuscitation. Crit Care Med 1979;7:293- 6. 10. Turner LM, Parsons M, Luetkemeyer RC, Ruthman JC, Anderson RJ, Aldag JC. A comparison of epinephrine and methoxamine for resuscitation from electromechanical dissociation in human beings. Ann Emer Med 1988;17:443- 9. 11. Waldhausen E, Keser G, Marquaradt B. Anaphylactic shock. Anaesthetist 1987;36: 150-8. Competing interests: None declared Authors response Andrew P C McLeanTooke, SpR in Immunology Royal victoria Infirmary, NewcastleUpon-Tyne, NE2 2TB., Claire A Bethune, Gavin P Spickett Send response to journal: Re: Authors response 10 December 2003 In response to 'algorithm illogical', the presence of a systemic reaction i.e. a reaction away from the site of contact would warrant consideration about the need for an adrenaline autoinjector. The reaction does not have to be severe to be systemic - thus a child with widespread urticaria following peanut ingestion should be followed on the protocol and risk assessed. As stated ' patients at high risk are those with asthma; reaction to trace allergen only; repeated exposure to allergen likely and lack of access to emergency medical care'. In reply to Prof. Sivagnanams comments I would agree the clear message here is that IM is the preferred route for adrenaline administration in anaphylaxis. As for cocaine or uncontrolled hyperthyroidism and concurrent use of adrenaline I would still consider its use RELATIVELY contraindicated. If the reaction is severe and failing to respond to other interventions including fluid administration, antihistamine and steroids then the use of adrenaline may be appropriate. The dosage is not clear but I would certainly recommend a reduced dose. As such I would not recommend administration of adrenaline without electrocardiographic monitoring or in the presence of appropriately trained staff, and I would certainly not give these patients an adrenaline auto-injector. Lastly, in reply to 'Need for working definition' whilst a the working definition of anaphylaxis given involves either respiratory difficulty or hypotension this will need to be in the context of an allergic history and is a clinical diagnosis. An episode of hypotension following a vasovagal episode does not therefore come under the umbrella of anaphylaxis. In some cases it may not be clear whether a hypotensive episode is a vaso-vagal reaction versus anaphylaxis, and I would suggest if there is a realistic possibility that this could be anaphylaxis then I would treat for such. Competing interests: None declared A clear link between adrenaline intravenous administration and severe cardiovascular effects Sergio Abanades, Clinical Pharmacology Resident Institut Municipal d'Investigació Mèdica. Barcelona 08003. Spain, Joan Buch. Clinical Hematology Resident. Hospital del Mar Send response to journal: Re: A clear link 11 December 2003 We read with much interest the article by McLean-Tooke et al (1). They mentioned that published reports of fatal cardiac arrhythmias and myocardial infarction associated to intravenous adrenaline often fail to state clearly that other factors including hypoxia, acidosis, or the direct action of inflammatory mediators, maybe, at least in part, responsible for the cardiovascular complications. Here we describe a case in which a clear relationship between the administration of intravenous adrenaline and cardiovascular complications was found: A 29 year-old woman current smoker with a medical history of between adrenaline intravenous administration and severe cardiovascular effects hypercholesterolemia. She was being studied for recurrent idiopathic angio -oedema. She was under treatment with topic acyclovir for herpes simplex labialis 48 hours before arriving to our emergency room. She came 20 minutes after the last acyclovir application presenting lip and laryngeal angio-oedema and hypotension and showing evident signs of anaphylactic shock. Hydrocortisone (200 mg intravenous) was administrated and an intramuscular adrenaline 1 mg preparation (1:1000) was administered intravenously in error. The patient developed central chest pain and the electrocardiogram showed ischemic changes followed by auto-limited ventricular tachycardia and acute pulmonary edema. Hypoxia and acidosis were not presented with normal acid-base values. She required noninvasive positive pressure ventilation followed by furosemide and dobutamine administration. The patient improved with a complete recovery. A complete cardiac study performed showed no evidence of myocardial disease. In this case due to an error in the route of administration, a clear link was found between adrenaline intravenous administration and myocardial ischemia and ventricular tachycardia. We can exclude other causes of acute coronary syndrome like hypoxia, acidosis or myocardial disease, and so we can conclude that intravenous adrenaline was the main cause. We agree that major adverse effects may occur when adrenaline is given too rapidly, inadequately diluted, or in excessive dose. Our case shows that intravenous adrenaline administration may lead to severe cardiovascular effects. 1. McLean-Tooke A, Bethune CA, Fay AC, Spickett GP. Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence?. BMJ 2003;3 Competing interests: None declared Observation after adrenaline: what is the evidence? Martin F Wiese, lecturer Emergency Department, St. Mary's Hospital, Praed St, London WC1N 3RA, Catherine Johnson, senior house officer and John A. Henry, professor Send response to journal: Re: Observation after adrenaline: what is the evidence? 11 December 2003 EDITOR – As emergency physicians, we would have liked to see the informative review by McLean-Tooke et al. [1] completed by a discussion of the need for hospital observation following the use of adrenaline for anaphylaxis. In accordance with current guidelines, [2,3] many patients attending emergency departments (ED) in the UK with an allergic reaction will be admitted for a period of observation if they have required adrenaline. The rationale for this is the risk of a secondary event after resolution of initial symptoms (the so-called biphasic reaction). The reported incidence of such reactions varies between 3 and 20%. [4,5] The mean time to onset of the secondary event is reported to be 10 hours, but they may occur as late as 24-36 hours after the initial reaction. [5] The available evidence in this area is limited to small case series. Most of those studies provide neither information about patient disposition nor duration of observation following resolution of symptoms. While secondary reactions are said to be potentially equally or more severe than the first one, most are probably mild. [4] There are no published reports about adverse outcomes from secondary reactions in patients discharged from the ED. The study by Gold and Sainsbury quoted by McLean-Tooke et al. found a reduced need for hospital admission in children treated with a correct dose of adrenaline by auto-injector in the community. This implies that admission may not be mandatory. Further evidence is needed to guide decisions about the place and duration of observation necessary following the use of adrenaline for anaphylaxis. At present, however, there is no indication for admission of all patients treated. 1. McLean-Tooke APC, Bethune CA, Fay AC et al. Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence? BMJ 2003;327:1332-5 2. Gavalas M, Sadana A, Metcalf S. Guidelines for the management of anaphylaxis in the emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med 1998; 15: 96-8. 3. Project Team of the Resuscitation Council (UK). The emergency medical treatment of anaphylactic reactions for first medical responders and for community nurses. Revised Jan 2002. www.resus.org.uk/pages/ reaction.htm 4. Brady WJ Jr, Luber S, Carter CT et al. Multiphasic anaphylaxis: an uncommon event in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 1997; 4:193-7. 5. Ellis AK, Day JH. Diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis. CMAJ 2003;169:307-11. Competing interests: None declared Subcutaneous adrenaline for anaphylaxis: compromise in high risk patient with mild symptoms Michal R Pijak, consultant in rheumatology, allergy and clinical immunology Slovak Medical University, Institute of Preventive and Clinical Medicine,, Frantisek Gazdik, Katarina Gazdikova Send response to journal: Re: Subcutaneous adrenaline for anaphylaxis: compromise in high risk patient with mild symptoms 19 December 2003 Subcutaneous adrenaline for anaphylaxis: compromise in high risk patient with mild symptoms EDITOR-McLean-Tooke et al state that "mild reactions such as angioedema and urticaria without airway involvement would not be described as anaphylaxis." (1) Although this statement is in line with current guidelines, confusion arises because more than half of the patients may have mild symptoms for one hour or more before severe respiratory compromise develop.(2) This may increase the risk of late administration of adrenaline which is generally associated with poor outcome. We welcome that history of severe reaction was selected as the main criterion in the algorithm for identifying patients who may benefit from an adrenaline auto-injector. However, the authors paradoxically introduced another source of confusion, by claiming that "the severity of previous reactions does not determine the severity of future reactions" Most importantly, they failed to explain under what circumstances should adrenaline be administered in a high risk patient with mild symptoms. Considering that benign allergic reactions should not be treated with adrenaline(3) and that the potential for misdiagnosis in high risk patient with mild symptoms is not known, we suggest compromise solution: to administer adrenaline subcutaneously instead of intramuscularly. The potential for harm following subcutaneous adrenaline administration is extremely small,(4) and its efficacy for prevention of anaphylaxis has recently been documented.(5) Finally, we would like to stress that the use of adrenaline with milder symptoms will depend on patient´s history. Several factors mentioned by authors seem to predispose individuals to more severe anaphylaxis, including a history of previous severe reaction, asthma, reaction to trace allergen and lack of access to emergency medical care. A number of other factors may lower the threshold for when to administer adrenaline eg, if the reaction is provoked by peanut, tree nuts, or seafood, personal history of atopy, adolescence (especially late teens), failure to identify the responsible allergen in the meal. Michal R Pijak, consultant in rheumatology, allergy and clinical immunology Frantisek Gazdik, associate professor of clinical immunology Katarina Gazdikova, associate professor of clinical pharmacology Slovak Medical University, Institute of Preventive and Clinical Medicine, Limbova 12, 833 03 Bratislava, Slovakia 1. McLean-Tooke AP, Bethune CA, Fay AC, Spickett GP. Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence? BMJ 2003;327:1332-5. 2. Sampson HA, Mendelson L, Rosen JP. Fatal and near-fatal anaphylactic reactions to food in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 1992;327:380-4. 3. Hourihane JO'B, Warner JO. Benign allergic reactions should not be treated with adrenaline. BMJ 1995;311:1434. 4. Cone DC; National Association of EMS Physicians Standards and Clinical Practice Committee. Subcutaneous epinephrine for out-ofhospital treatment of anaphylaxis. National Association of EMS Physicians Standards and Clinical Practice Committee. Prehosp Emerg Care 2002;6:67-8. 5. Premawardhena AP, de Silva CE, Fonseka MM, Gunatilake SB, de Silva HJ. Low dose subcutaneous adrenaline to prevent acute adverse reactions to antivenom serum in people bitten by snakes: randomised, placebo controlled trial. BMJ 1999;318:1041-3. Competing interests: None declared Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: 21 December what is the risk and benefit? Michal R Pijak, consultant in rheumatology, allergy and clinical immunology Slovak Medical University, Institute of Preventive and Clinical Medicine,, Frantisek Gazdik, Katarina Gazdikova Send response to journal: Re: Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the risk and benefit? 2003 EDITOR, McLean-Tooke et al (1) state that "the benefit of using appropriate doses of intramuscular adrenaline far exceeds the risk" and that "intravenous route should be reserved for those with unresponsive anaphylaxis." However, such claims are inconsistent with the statement that "As there are no controlled trials there is no way to estimate the risk in relation to benefit" and readers get a very misleading message. We would like to emphasize that it is the time of maximum plasma adrenaline concentrations that affects the outcome. There is now good clinical and experimental evidence indicating that delay of administration of adrenaline is associated with both increased risk and decreased benefit. (2,3) Intravenous administration of adrenaline ensures rapid delivery to its site of action and avoids the problem of erratic and variable absorption. In a view of this, the expert use of high dilution intravenous adrenaline in hospitals with appropriate monitoring may be more optimal care for a patient with severe anaphylaxis. The evidence for safety of intravenous adrenaline in a small series of younger adults with acute life-threatening asthma has recently been documented.(4) As authors rightly point out, increased risk is associated with adrenaline overdose, usually caused by inappropriate administration. This risk is relatively high, because therapeutic and toxic doses are rather similar. Non-intravenous adrenaline administration is therefore entirely appropriate in initial pharmacologic management of anaphylaxis in a setting without monitoring and intensive care facilities. Intramuscular route seems to be superior to the subcutanous route, because of faster absorption. Nevertheless, pharmacokinetic data suggest that subcutaneous route might be safer. We have therefore proposed that for high risk patients with mild symptoms, subcutanous route would be better option.(5). In low risk patient with mild reaction, however, the risks of adrenaline may outweigh the benefits, even if administered by subcutaneous route. Michal R Pijak, consultant in rheumatology, allergy and clinical immunology, Frantisek Gazdik, associate professor of clinical immunology, Katarina Gazdikova, associate professor of clinical pharmacology, Slovak Medical University, Institute of Preventive and Clinical Medicine, Limbova 12, 833 03 Bratislava, Slovakia 1. McLean-Tooke AP, Bethune CA, Fay AC, Spickett GP. Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence? BMJ 2003;327:1332-5. 2. Pumphrey RSH. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study of fatal reactions. Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:1144-50. 3. Bautista E, Simons FE, Simons KJ, Becker AB, Duke K, Tillett M et al. Epinephrine fails to hasten hemodynamic recovery in fully developed canine anaphylactic shock. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;128:151-64. 4. Smith D, Riel J, Tilles I, Kino R, Lis J, Hoffman JR. Intravenous epinephrine in life-threatening asthma. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:70611. 5. Pijak MR, Gazdik F, Gazdikova K. Subcutaneous adrenaline for anaphylaxis: compromise in high risk patient with mild symptoms. http://bmj.com/cgi/eletters/327/7427/1332#44125, 19 Dec 2003. Competing interests: None declared Does adrenaline have an important drug interaction with alpha adrenergic receptor blocking drugs? Alan Watson, General Practitioner Tranmere South Australia 5073 Send response to journal: Re: Does adrenaline have an important drug interaction with alpha adrenergic receptor blocking drugs? 22 December 2003 Dr McLean - Tooke and colleagues list systemic and topical beta adrenergic blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors and cocaine as having important drug interactions with adrenaline. I suggest that any drug with alpha adrenergic receptor blocking activity should be included. In 1995 I managed a patient with an anaphylactic collapse following a bee sting who was taking the alpha 1 receptor blocker prazosin for hypertension. He appeared to have resistant hypotension following self administered adrenaline by auto-injector and general practitioner administered adrenaline (1). In 1998 a patient from my practice who was on long term thioridazine and amitriptyline had a sudden collapse presumed to be anaphylactic in nature where there was prolonged hypotension. Both of these drugs have a major alpha 1 adrenergic receptor blocking action. The hypotension failed to respond to adrenaline infusions but there was an eventual response to infusion with a pure alpha 1 receptor agonist (2). Prior to publishing this article I carried out a literature search and found that the only published studies of the reverse adrenaline effect related to animal studies. The reverse adrenaline effect has been described in standard pharmacology texts for years. The expectation is that parenteral adrenaline will increase blood pressure in the recipient. In patients on drugs with alpha 1 adrenergic receptor blocking activity however the adrenaline is unable to cause vasoconstriction in the skin and viscera because the alpha receptors on the smooth muscle of the arterioles of those organs are blocked. The adrenaline is free to act on the beta 2 receptors on the smooth muscle of the arterioles of skeletal muscle to cause vasodilatation to prepare for “fight or flight” The net result is vasodilatation and exacerbation of hypotension. There are several cases published reviewing the speculative mechanisms of the sudden death of youths who were on drugs with alpha 1 adrenergic receptor blocking activity; either on tricyclic antidepressants alone or in combination with phenothiazines (3,4). There are likewise many unexplained deaths described in adults on thioridazine and other phenothiazines. These deaths are attributed usually to ventricular fibrillation related to prolongation of the QT interval. I suggest from pharmacology of the alpha adrenergic receptor blocking drugs that a reverse adrenaline effect (from endogenous or parenteral adrenaline) may exacerbate hypotension leading to a terminal arrhythmia secondary to electromechanical dissociation from profound hypotension. I would be interested to hear if other colleagues have had problems with resistant hypotension when using adrenaline for anaphylaxis in patients on alpha 1 receptor blockers. At the very least there are theoretical reasons for advising against the use of drugs with alpha 1 adrenergic receptor blocking activity in patients with a history of anaphylaxis. In anaphylaxis the drug history will rarely be available. Doctors should be aware that if hypotension is resistant to repeated doses of adrenaline the reverse adrenaline effect may need to be considered. References: 1. Watson A. Don’t get stung with the adrenergic blockers (beta or alpha). Australian Family Physician Vol. 24, No. 10, October 1995 1879 2. Watson A. Alpha adrenergic blockers and adrenaline- a mysterious collapse. Australian Family Physician Vol. 27 No. 8, August 1998 714715. 3. Popper CW, Zimnitzky B. Sudden death putatively related to desipramine treatment in youth: a fifth case and a review of speculative mechanisms. Journal Of Child And Adolescent Psychopharmacology Vol.5, No. 4, 1995 283-300. 4. Varley CK, McLennan J. Case study: two additional sudden deaths with tricyclic antidepressants. J.Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36:3, March 1997 390-394. Competing interests: None declared