ICC

advertisement

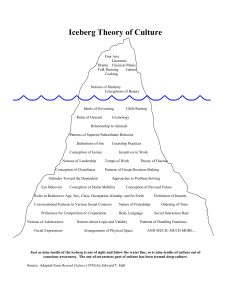

An introduction to Intercultural Communication (ICC) by Erik Hemming, Lecturer in Languages at the Åland Polytechnic in Mariehamn, Finland. Definitions, clarifications and simplifications Worldview and values The iceberg simile of culture and communication (appendix 1) can be seen as worldviews under the surface and the physical world above. Our worldview is mainly learned in our early years and remains subconscious to most people. It is very often mistaken for reality. This mistake leads to enormous problems, but in spite of this very few realise that part of the problem always lies in the way “reality” is perceived. Instead the problems induced by the worldview are included in it and projected away from the subject. Our internal world is a wonderful and very complex one. Since our nervous system has 300 billion neurons, each of them with some 5 thousand synapses, there is plenty of capacity to take in and process information from the physical world and from the surrounding people’s ways of understanding it. One crucial feature of our worldview is that it is built up of information that we have selected among an almost infinite mass of sensory input. Our subjectivity is our guiding principle in that selection; we even call it our identity. And without interest, intentions, and emotions, there would be no attention to anything outside of us. The beliefs that we hold as truths are there because they are linked to our interest, intentions, and emotions. This is how our internal world is built up and held together. To ourselves it seems to be a logical world without contradictions. Like electrically charged particles, the pieces of information we process, are turned so that the positive and the negative sides stay in balance. And the forces that keep them in place are strong. Attitudes are hard to change. They seem to us to be based on hard facts. But the facts that we know are always connected to feelings. And feelings are always positive or negative, never neutral. Therefore the facts are organised in value systems. These systems are extremely complicated and multifaceted. They will be discussed here in terms of dimensions in order to make tem possible to grasp. The following short list is included here in order to show how rich a worldview is: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Approaches to problem solving Arrangement of physical space Attitudes Attitudes to the dependent Body language Conception of beauty Conception of cleanliness Conception of justice Conception of past and future Conception of self Conception of status mobility 12. Conversational patterns in various social contexts 13. Cosmology 14. Courtship practices 15. Definition of insanity 16. 17. 18. 19. Definition of sin Eye behaviour Facial expressions Ideals governing child raising 20. 21. Incentives to work Informal relationships 22. 23. Loyalties Management styles 24. Motivations and commitments 25. Nature of friendship 26. Norms PB 1010 • FIN-22 111 • MARIEHAMN • FINLAND TELEPHONE: +358-18-5370 • FAX: +358-18-16913 E-MAIL: EHE@HA.AX WEB: WWW.HA.AX/ERIK 27. Notions of adolescence 28. Notions of leadership 29. 36. 37. 38. 39. Notions of logic and validity 30. 31. 32. Notions of modesty Ordering of time Patterns of group decision-making 33. Patterns of handling emotions 34. Patterns of superior/subordinate relations 35. Patterns of visual perception 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. Perceived rewards Personal aspirations Power networks Preference for competition or cooperation Relationships to animals Roles in relation to status by age, sex, class, occupation, kinship, etc. Rules of descent Social interaction rate Tempo of work Theory of disease Values Colliding values give rise to clashes of culture. What is right for you is wrong for me. But differences in communication codes can also be the problem, even if our values are harmonising. The codes are also a part of our culture. In our worldview the connections between our words and behaviour and what they mean is crystal clear. Codes and signs For communication to be efficient it needs to take place in a well-functioning group or society. This is different than a category of people. Some categories of people, such as, say medical doctors may understand each other better than say 38-year-old people do, but only people who stay in communication with each other for a long time learn to decode each other’s messages really well. Indeed they develop a code system of their own in such a group. The family is the best example of such a group. As for societies they are in communication in an impersonal yet constant way through their institutions. Note that there are countries where there is no common society in which all people are included, nor want to be included (due to the power distribution). A code is a rule that says that this sign or combination of signs represent this meaning. Based on good knowledge of what signs usually stand for we can learn to guess quite well what new, creative, combinations are intended to mean. But signs are produced whether there is an intention to do so or not. Quite frequently meanings are decoded without any person outside the receiver of the message being aware of any message being transmitted. Our nervous system is fully capable of producing what it sees fit to explain something that seems to need to be explained. That process goes backwards in time, looking for a cause to a perceived effect. Objectively this is wrong, but it may feel right at the time. One example of rationalisation when it works well is when a person burns her hand. She then retracts her hand in 0.1 second. But it takes 0.5 second to become aware of that, and even longer to figure out the reason she pulled the hand back. Part of the problem is that the amount of sensory input to our nervous system is so massive. Some 11 – 12 million bits of information is received per second. About 10 million is visual, 1 million is auditive and the rest represents taste, touch, smell, and input from the muscle sense. However, almost all of that is filtered out from our awareness. Only some 40 bits per second may be held aware. And the filtering is completely subconscious. So on what data is our worldview built? This is perhaps where the power of culture is most dramatically overwhelming. Codes are the attachments of meanings of single or combined signs. A sign is then the morpheme of communication, the smallest possible carrier of meaning. Close analysis of signs PB 1010 • FIN-22 111 • MARIEHAMN • FINLAND TELEPHONE: +358-18-5370 • FAX: +358-18-16913 E-MAIL: EHE@HA.AX WEB: WWW.HA.AX/ERIK may show that they are not so single or simple. A wink of an eye may consist of many components. But often it is enough to know that a person really did wink and then to guess correctly what that could have meant in that situation. To assign meaning to other people’s actions is called attribution. As a rule there are four possibilities: Actions are explained by either a) personal traits, b) states of mind, c) the situation, or d) culture. We tend to employ TRAIT far too often. Unfortunately this misconception then often spills over to innocent members of the category to which we have assigned the person whose actions we have “explained”. Instead the correct explanation more often is STATE, SITUATION, or (most common of all) CULTURE. Our subconsciously governed selection of sensory input greatly reinforces our tendency to faulty attributions. If we feel strongly about something we are more likely to notice it, provided there is an apt mental category at hand. There is a word for it: Stereotype. Added to this then the presence of unresolved traumas in our personal or societal history will provide nutrition for horrible prejudice of members of out-groups. This way worldviews and codes can lead people towards segregation and even hate. Dimensions of values Simplifying diversity As we saw from the list above the worldview of a person or a culture may simply not be grasped without simplifications. Researchers and authors have contributed with many suggestions to bring order in the confusion. One popular idea has been to group the conceptions, notions, preferences, attitudes, beliefs, values, and norms that make up a worldview along thematic lines. Such a line would then be organised from one extreme to its very opposite, including great many possible standpoints in between. In the following a few of these “dimensions” will be outlined briefly. Power: Most importantly this is a question of parent-child relations. They are linked to the presence of hierarchical structures in working life, school, and other areas of society. Groups vary very much as to the members’ acceptance of a strong leader. Individualism: With the advent of industrialism agriculture’s demand of collective efforts vanished. As people leave their villages they gain freedom, but lose a whole world of social meanings. This has not yet happened to most people on the earth. They might not wish to be independent or to make their own decisions if they have to give up the we-feeling. Masculinity: Cultures are soft or hard, nurturing or competitive, valuing either relations or money and possessions. This is reflected to some extent in the right-left scale in politics. Long-term orientation: A dimension emphasising the differences between the East and the West. Do we pick harmony or truth if we have to choose? Do we work for ourselves or for our grandchildren? Universalism: The wish to apply the same rules to everybody, whereas particularism is to have different rules for the in-group. Task centredness: People prioritise performing tasks instead of taking care of their relations to other people. This is often combined with a mono-chronic time conception, whereas people centredness goes well with a poly-chronic conception of time. Modern, industrialised city life, possibly also climate, influence societies in this dimension. PB 1010 • FIN-22 111 • MARIEHAMN • FINLAND TELEPHONE: +358-18-5370 • FAX: +358-18-16913 E-MAIL: EHE@HA.AX WEB: WWW.HA.AX/ERIK Success in ICC Us and them Tribes living traditionally under scarce conditions have often had to fight for their livelihood. It has been natural to prioritise one’s own in-group then if the resources have not been sufficient – indeed even if they have been. Today we are not much different, except if people realise deep inside that there are great benefits for both parties if they start to cooperate and learn from each other. The cause of this new interdependence is globalisation. However, it seems to almost genetically inevitable that people will think in terms of Us and Them. By taking a look at how this works it may be possible for some to attain some level of awareness of their own tendencies to exalt their own culture (group or society) and to depreciate other peoples’ culture. But it is also true that many people feel attracted to other cultures – and even to exaggerate their positive qualities, perhaps out of boredom with their own society. If groups meet or at least notice each other, communication is more difficult to set up than between individuals, and much easier to spoil. Wars start that way. The responsibility is much with the leaders who have a choice between demonising or humanising the other group in their rhetoric. In-group dynamics often makes demonising easier. In order to open up communication there needs to be – communication. The code systems must merge to a certain point. Somebody must want to overcome the confidence gap, and to believe it can be overcome. Traditionally, starting communication has taken place in rites, such as sitting down around a fire, or eating or drinking something together. Neighbours may borrow a cup of sugar to start the process. If a misunderstanding takes place at this early stage, normally communication is interrupted. Group members explain this with ideas of the other party’s faults, on both sides. But sometimes people do go on spending time with the “others”, just like Kevin Costner in Dances with Wolves. In the course of a lot of time, close and multi-sensory communication will have taught people so much about each other that they seldom misunderstand the “others” – in fact, they have become “us”. Ethnorelativism or cultural relativism Of course it is easier to just communicate with those who are very much like us. “Birds of a feather flock together.” If we talk to somebody and hear that person react just like we would to a film or book or political situation it is easy to think of her as a friend. Probably we have an unsatisfied need for confirmation of our worldview. As we encounter and spend time with people from many different backgrounds and parts of the world with an open mind, we change as persons. This is the same as to say that our worldview changes. New categories are formed and old ones are split up into thousands. Nothing we once believed in holds true forever and we often go through crises in our value systems. Does this mean that everything is OK just because there are people who think so somewhere in this world? That question has better not be answered – not by outsiders. Take the mothersin-law in India who have burnt their daughters-in-law. There is a special prison department for them in Delhi. One should surely condemn the behaviour, but we will never be in a situation where we can condemn them. Now, this is easy to write or say, but hard to live by. We are in a perfectly good position to judge activities inside our own culture, but we have to remember that activities performed by people in other cultures actually do make sense to them. There simply is no objective ethical standard. I myself find that hard to live with. PB 1010 • FIN-22 111 • MARIEHAMN • FINLAND TELEPHONE: +358-18-5370 • FAX: +358-18-16913 E-MAIL: EHE@HA.AX WEB: WWW.HA.AX/ERIK Appendix 1 Icebergs colliding under the surface The physical world OUTER REALITY COMMUNICATION CODES: Interpretation - negotiation Worldview INNER REALITY Worldview INNER REALITY PB 1010 • FIN-22 111 • MARIEHAMN • FINLAND TELEPHONE: +358-18-5370 • FAX: +358-18-16913 E-MAIL: EHE@HA.AX WEB: WWW.HA.AX/ERIK