chapter two - Hartford Institute for Religion Research

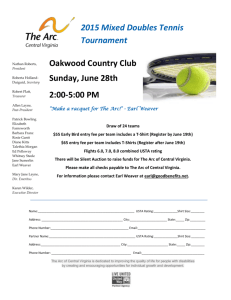

advertisement