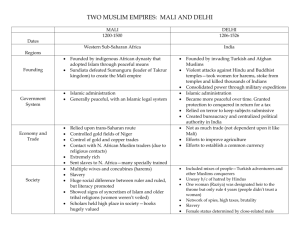

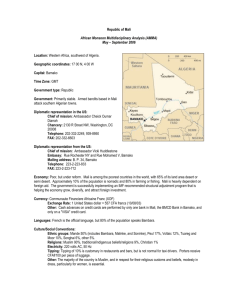

Mali - encap

advertisement