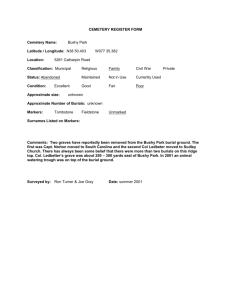

The Early Anglo Saxon Census draft 2

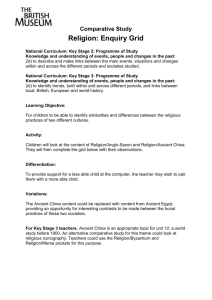

advertisement