Running Head: LEVINAS AND THE SEXUAL ENCOUNTER

A Dialogue of Searching: Levinas and The Sexual Encounter

Patrick Cheatham

Presented at 8th Annual Psychology for the Other Conference, Seattle, WA

October 23, 2010

1

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

2

Sex has power. Sex has the capacity to change people’s self-experiences, transform

relationships, and even challenge the societies in which we live. Sex sells. The history of

advertising is rife with associating sex with the non-sexual, so people will purchase a product or

way of life. As in the case of pornography and prostitution, sex sells itself. People will pay to

have sex. People will pay to watch sex. People will pay to experience the fantasy of sex and then

have sex by themselves. Sometimes, sex is treated like a secret that must be managed for the sake

of propriety. In many parts of the world, woman can be physically punished for just the

implication of sexuality. At other times, sex is treated as a self-evident, natural fact of human life.

Magazines run articles discussing the top ten sexual techniques to make your lover have an

orgasm. Sex happens when people like each other, and it even happens when they do not. Since

sex can be many things to many people at many different times, any phenomenology of sex must

begin by addressing the potential foundational elements of the experience. These elements must

be common to a wide range of sexual experiences and encounters, be they heterosexual,

homosexual, and everything in between and otherwise.

One such foundational element of sexual experiences consists of the interaction that

occurs between two partners. Of course, sexual experiences do not require the presence of a

second person, and sometimes, sexual experiences consist of more than two people. However,

even when it happens solitarily or within a group, the encounter with another person can

characterize the experience. For instance, masturbation commonly involves the reminiscence of

previous sexual partners or the fantasy of an experience with another person, so even these

solitary sexual experiences possess an intentionality toward another. Group experiences offer

more variety regarding the other person, but even here there will be moments, perhaps ephemeral,

in which one other person stands out within the experience and becomes an object of desire.

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

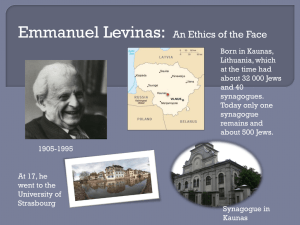

To assist with examining this aspect of the sexual experience, I will utilize the

phenomenology of Emmanuel Levinas as a framework for disclosing the element of dialogue

between sexual partners. Emmanuel Levinas was a 20th century phenomenologist who focused

his attention on the ethics of intersubjective relationships. As opposed to other thinkers who also

focused on this subject, e.g. Martin Buber, Levinas emphasized the absolute difference between

the self and the Other. In this relationship the self and the Other ab-solve themselves of relation,

ab-solve meaning to set free and an example of Levinas’ flair for semantic reverse engineering.

This separation actually founds the ethical experience of the Other. Levinas believed that a true

ethical relationship could only happen when the self cannot turn the Other into an object of

knowledge. While not focusing extensively on sex and sexuality, Levinas (1969) briefly

explicated his thoughts on the matter in late sections of Totality and Infinity by expanding his

conception of the face-to-face ethical encounter to matters of Eros and fecundity.

The Levinasian Encounter with the Other

Before outlining his notion of the face-to-face encounter with the Other as the

precondition for any conception of ethics, Levinas’ metaphysics must be discussed, as it detailed

the condition of the absolute relationship. In Totality and Infinity, Levinas (1969) began by

describing the self as an inherently egoic existence. The self exists in a nearly solipsistic state,

and separation defines its relation to the world (1969, p. 102). Levinas called the independent

existence of the world “the elemental” and described it as “the non-possessable which envelops

or contains without being able to be contained or enveloped” (1969, p. 131). Separation, though,

does not imply disconnection from the world. The self relates to the world in a fashion that

Levinas termed spontaneous enjoyment and nourishment. The self takes from the world that

3

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

4

which it needs for sustenance, but more than just this, it enjoys this sustenance on a basic sensual

level. As Levinas stated, “We live from ‘good soup,’ air, light, spectacles, work, ideas, sleep, etc.

. . . These are not objects of representations. We live from them” (1969, p. 110).

This spontaneous enjoyment of the elemental, predicated on its independence from the

one who enjoys it, distinguishes itself as a self-referential act (Levinas, 1969). The self maintains

distance from the elemental, which cannot be contained, but the very act of enjoyment and

nourishment relates the elemental to the furthering of the self. Even though one cannot possess

the elemental, one can always co-opt it. Enjoyment and nourishment involve the transmutation of

the non-possessable elemental into the same. The elemental feeds the self and then becomes the

self. Out of this co-option, the self creates a home, the place from which ipseity encounters the

world. Levinas stated,

The privileged role of the home does not consist in being the end of human activity but in

being its condition, and in this sense its commencement. The recollection necessary for

nature to be able to be represented and worked over, for it to first take form as a world, is

accomplished as the home. (1969, p. 152)

The home distinguishes the self as what Levinas called interiority. Interiority indicates both

residence in the elemental, the medium from which ipseity enjoys, and a withdrawal from it. He

wrote, “Concretely speaking the dwelling is not situated in the objective world, but the objective

world is situated by relation to my dwelling” (1969, p. 153). One’s dwelling situates the

perspective on an objective world and holds no sense of the self’s limits, as the elemental can

become a consumable object of consciousness. It is as if the self holds the perspective of a freefloating consciousness. Levinas likened this to the Greek myth of Gyges, the one who sees and

remains unseen.

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

5

Levinas (1969) stated that this self-referential, unbounded existence does not cease until

the encounter with the face of the Other, the subjectivity of another person. The self encounters in

the Other something absolutely separate and resistant to being subsumed in an act of enjoyment.

While the Other seems to be part of the elemental, especially if the conceptualization of the

elemental widens to include social relations, the Other infinitely overflows any of the self’s

conceptualization of it. Levinas wrote, “His face in which his epiphany is produced and which

appeals to me breaks with the world that can be common to us” (1969, p. 194). The Other

presents as more than what the self can understand and even perceive, as perception includes preunderstanding within the act. The Other as incomprehensible ultimately questions the self’s

enjoyment of the elemental world, as it erects an obstacle to the unlimited and self-interested

movement in the elemental. Moreover, the incomprehensible Other can see the self. Gyges is no

longer invisible. In confronting this, the self must pause within its spontaneity. This pause

complicates its prior sense of freedom and introduces an inherent weakness in the task of

understanding the face of infinity. Levinas asserted that this encounter ultimately forces the self

to recognize the primacy of the Other, one that holds a position of transcendence over the

elemental and the self.

Levinas’ conceptualization of the relationship between the self and the Other, one of

separation and transcendence, though, contained a tension within it (Levinas, 1969). While

Levinas valorized the Other’s ineffability, he did not overlook the self’s desire to objectify the

Other, to experience the Other as less than transcendent and similar to the elemental. The self

often attempts to reduce the infinite nature of the Other to that of an object of consciousness, an

act Levinas termed totalization. Through totalization, the self experiences the Other in a static,

objectified, and potentially utilitarian manner. It could essentially regard the Other as part of the

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

6

elemental and a source of enjoyment and nourishment. The self’s ipseity would not be ruptured or

questioned by the encounter with the Other in this manner. However, Levinas believed that

recognition of the Other’s otherness, primarily the inability to become an object of the self’s

consciousness but also the ability for the Other to actually see the self, would always resist the

move toward totalization. The infinite face of the Other always recedes from the self, so all that

becomes encountered is a concrete, static visage and those fleeting moments of the Other’s

infinitude that halt the self’s egoism.

An Illustrative Example

Before shifting focus from the general outline of Levinas’ ethical encounter to a

consideration of its usefulness in regard to the sexual encounter, a brief example may help

provide something tangible for our consideration. Imagine two people spending the night

together. In order to keep the focus on the relational dynamics between the partners, specific

gender designations will not be utilized, and they will just be called Partner One and Partner Two.

Throughout the evening, the partners have discussed whatever is happening in their lives: their

jobs, families, friends, etc, and this conversation continues late into the evening. They are on

opposite ends of the couch, but they sit toward each other. The conversation frequently reaches

faint lulls, and Partner One finds it hard to look directly at Partner Two during these moments.

When Partner One does look, Partner Two looks back and smiles. Partner Two starts to speak

softly and shifts weight to lean closer toward the other. Partner One smiles at the sight of this and

leans in reciprocity. They both feel a distinct sense of momentary anticipation in the room.

They touch arms and draw closer to each other in a way that has become familiar over the

span of their relationship. Despite the familiarity, though, each time also feels distinctly new.

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

7

They kiss each other lightly at first and then more forcefully as time passes. Partner Two breaks

from the kiss and looks into the other’s eyes. Partner Two’s heart races at the recall of the last

time they spent the night with each other. Partner One returns the gaze and tentatively moves a

hand toward the buttons of Partner Two’s shirt. Within minutes, articles of clothing have been

thrown to the floor, and their bodies are pressed into each other.

They lie together on the couch and run their hands along the outlines of each other’s body,

feeling their muscles tighten with each touch. Partner One notices the way Partner Two’s clavicle

shifts as they press into each other, and Partner Two clutches the hair at the back of Partner One’s

head. The room feels warm to them now, and their skin sticks slightly to each other. They both

have their eyes closed most of the time, but their other senses (taste, touch, smell, hearing, even

proprioception) give them all the information they need to explore and find pleasure. Time feels

like it stands still, or maybe it no longer matters in the usual way. Afterward, they lie on the

couch together and talk about what they liked about sex this time. Maybe they laugh about

forgetting to close the curtains to the living room. The room feels less warm now, so they huddle

together against the realization of the cool air on their bodies. They both know that they will

sleep heavily tonight.

Levinasian Sexual Dialogue

Consider the experiential chaos of the moment just described. The sexual encounter can

involve a dizzying array of sensations, thoughts, fantasies, and feelings. We can take basic steps

toward entering the situation, though, by way of Levinas’ notion of the Other as transcendent.

What cannot be comprehended and does not exist solely for the self can be taught through

revelation by the transcendent Other (Levinas, 1969). Levinas believed that this teaching through

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

8

revelation occurred through the act of discourse, which for him mainly meant verbal

communication. While revelation uses language as the medium, the Other as Other cannot be

properly thematized through language. However, Levinas (1969) believed that the elemental can

be thematized for the Other and discourse rests on this. In fact, that which exists does so for the

Other, according to Levinas. Levinas said, “The Other, the signifier, manifests himself in speech

by speaking of the world and not himself; he manifests himself by proposing the world, by

thematizing it” (Levinas, 1969, p. 96). According to Levinas, the only possible bridge between

the self and the Other, albeit a tentative one, resides in the play of language and the proposition of

the elemental, a mutual world.

When considering this,, the sexual encounter can be one such moment in which the self

and the Other propose a mutual world through non-verbal communication. Of course, language

can play an integral and often taken for granted role in sex, but consider the above example of a

sexual encounter. While verbal language likely played a factor in the desire between the partners

and its culmination, the non-verbal communication formed a large part of the encounter. The

clutching of hair, the movement of bones under skin, the slide of hands along a body: each nonverbal bridge drew the partners closer to each other and created, at least for the encounter, a

world in which an encounter could happen.

If a mutual world has been proposed, then how do our two partners find each other within

it? From the very start of desiring another person, sex involves an indispensable element of

objectification. By objectification, I do not mean just the prosaic conception of seeing physical

attributes as a person’s primary source of value, although this honestly plays a role. I instead

mean that the desired other inspires a need for possession and comprehension. One person wants

the other, and this desire has a visceral feel to it, a hunger. Levinas (1969) discussed the

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

9

enjoyment and nourishment that the self takes from the elemental, and this is perhaps a close

approximation of the objectified sensibility to sexual desire. In sexual desire, the self wants to coopt the desired and make it part of itself. Ideally, of course, the Other wants to be desired, and

there is no broaching of a boundary here. The Other is a willing participant in the self’s egoic act

of nourishment and visceral enjoyment.

Within the Levinasian perspective, though, objectification of the Other fails, even if the

Other consents. It simply cannot be fulfilled. The Other eludes our desire in the same manner that

the Other eludes our comprehension. The infinity of the Other overflows its concrete and static

representations, even the sexual ones. The Other’s escape from the self’s desire, though, does not

diminish it. In fact, it reaffirms and even strengthens the desire. The self wants what it cannot

have, and this failed quest increases the desire for the Other. This is an important point to sexual

objectification. It cannot be completed, and perhaps its failure sustains the self’s mission to

objectify. The self ultimately desires the very frustration of desire.

Just as the Other eludes the self’s desire, though, the self experiences being desired by the

Other. The escape of the Other occurs concurrently with the Other’s pursuit of the self. The Other

seems to demand nourishment and enjoyment, and the self, in the face of the transcendent other,

wants to oblige. In order to get closer to the Other, the self must be willing to be an object of

sexual satisfaction for the Other. This cycle of objectification and escape forms a circle of sexual

desire and the attempt to satisfy it. This circular movement between the incompleteness of

objectifying the Other while also being objectified by the Other has the characteristic of verbal

dialogue in the Levinasian sense. This dialogue involves the repetition of totalization, the failure

of totalization, glimpses of infinitude, and the loss of that glimpse.

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

10

Uncertain Intimacy and the Loss of Agency

As a final note, conceptualizing the sexual encounter in this manner raises a question

about the self’s agency. In order to be intimate with another person, the self must relinquish a

certain amount of control over the process The self cannot dictate how the Other acts on his or

her desire, and the self must be willing to be objectified for the Other. This is both a sacrifice for

the sexual encounter but also a factor of what makes it alluring. Without agency and the self’s

egoic mission, though, what remains? In discussing erotic sensibility, Levinas (1969) highlighted

the notion of the caress. He wrote, “[The caress] searches, it forages. It is not an intentionality of

disclosure but of search: a movement unto the invisible. In a certain sense, it expresses love, but

suffers from an inability to tell it” (1969, p. 258). Levinas further noted, “the discovered does not

lose its mystery in the discovery, the hidden is not disclosed, the night is not dispersed” (1969, p.

260).

The Levinasian caress within sexual experience presents a picture of sexual intimacy that

is very different from usual ideas. Intimacy can commonly mean familiarity and certitude, and

when a relationship lacks it, partners can feel unknown and uneasy about each other. Familiarity

and intimacy, though, do not need to go hand in hand. From the conceptualization just proposed,

Levinasian intimacy valorizes unfamiliarity. It thrives on this sense of unfamiliarity, and the

caress, a halting question made physical between two partners, can lead toward greater intimacy.

It presents itself as a glance that lightly touches the surface. It does not demand intrusion but

instead asks for an invitation.

Levinas and the Sexual Encounter

11

References

Levinas, E. (1969). Totality and infinity: An essay on exteriority. (A. Lingis, Trans.).

Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. (Original work published 1961).