A summary of some relevant cognitive science theory

advertisement

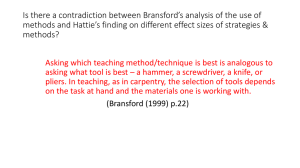

Theoretical Support for Story-Centered Curricula Story-Centered Curricula (SCC) are, perhaps, the ultimate form of integrated learning experience to date. An SCC has no classes, no required lectures, and no tests. Instead, students work in teams on authentic, realistically complex projects. A project comprises a carefully designed progression of tasks, each designed to require targeted knowledge and skills for successful completion. Student teams working on these tasks are coached by both academic faculty and experienced industrial practitioners. They also have access to reading materials (and sometimes even video lecture material and other resources such as simulations) indexed to specific aspects of tasks. Thus, they learn just in time in a context that is likely to promote transfer to similar problem solving in the future. Student performance is evaluated according to the quality of authentic deliverables produced by a team. Individual achievements are differentially weighed by mentor evaluations of their interactions with students and by employing peer evaluations in which students evaluate their own and other students’ performance at the conclusion of each task according to a well-defined, task-appropriate rubric. The design of Story-Centered Curricula draws on theoretical work and empirical results from many researchers. Its theoretical basis is Schank’s theory of Dynamic Memory (Schank 1982, 1999) which posits that memory is primarily an organization of specific experiences and that expectation failures in the application of those experiences to new situations are the basic triggers for learning. Reliable transfer of experience only occurs when the learning context is highly similar to the application context (Bransford, J. D., Franks, J. J., Vye, N. J., & Sherwood, R. D. 1989; Tulving, E., & Thompson, D. M. 1973), and such transfer can be potentiated by transfer-appropriate processing (Morris, Bransford, and Franks 1977). In addition to our own work on Goal-Based Scenarios (e.g., Schank, R., A. Fano, B. Bell, and M. Jona. 1993; Bell, B., R. Bareiss, and R. Beckwith. 1993), other researchers have addressed the creation of authentic, contextualized learning experiences (e.g., Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. 1989; Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt. 1991; Lave, J., & Wenger, E. 1991; Greeno, J. G., Collins, A., & Resnick, L. B. 1995; Collins, A. 1996; Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R., Eds. 2000). Two lines of research stand out as particularly relevant: One, Cognitive Apprenticeship (Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. 1989), suggests that problem solving skills can be taught in the context of scaffolded problem solving by observation of modeling by expert practitioners and by reflection on student experiences. The second, Anchored Instruction (Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt. 1991), defines the characteristics of a problem solving context that supports the acquisition of transferable skills. In the specific area of professional education, Story-Centered Curricula are most similar to Problem-Based Learning (e.g., Barrows, H. S. 1998; Hmelo, C. E. 1994) in that PBL replaces conventional curricula, e.g., in medicine, with team-based, student-directed learning in the context of authentic cases. Note, however, that Story-Centered Curricula differ from “classic: problem-based learning, in that: - - students work within a single coherent framework for the duration of the curriculum thus minimizing the need for repeated “incidental” learning of case materials the progression of tasks builds organically on earlier tasks (in contrast to PBL in which a series of cases is organized primarily by difficulty) the student is expected to act (e.g., to implement a solution) and sees the outcome of his or her actions (in contrast to classic PBL in which the foci are diagnosis and perhaps treatment planning, but the student does not get to actually implement the treatment and see the result) SCC’s are designed to make the supporting resources -- reference materials such as books, articles, videos, access to experts -- that the student is most likely to need readily available with clear pointers, instead of requiring him or her to interrupt problem solving, perhaps for an extended period, to search for them. (PBL has a very strong emphasis on developing self-directed learning/research strategies; while SCC’s emphasize this too, the primary emphasis is on successful task performance.) In addition to cognitive, learning benefits working in the context of an authentic “story” also has motivational benefits for students (e.g., McCombs, B. L. 1996; Schank, R., & Neaman, A. In Press). References Barrows, HS, (1998). The essentials of problem-based learning. Journal of Dental Education. 62:9, 630-633. Bell, B., R. Bareiss, and R. Beckwith. 1993. Sickle Cell Counselor: A Prototype GoalBased Scenario for Instruction in a Museum Environment. Journal of the Learning Sciences 3:4. 347-386. Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. Bransford, J. D., Franks, J. J., Vye, N. J., & Sherwood, R. D. (1989). New approaches to instruction: because wisdom can't be told. In S. Vosniadou & A. Ortony (Eds.), Similarity and Analogical Reasoning (pp. 470 - 497). New York: Cambridge University Press. Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning. Educational Researcher(January-February), 32 - 42. Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt. 1991. The Jasper Series: A generative approach to improving mathematical thinking. In This Year in School Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Cited in Bruer, J. (1993) Schools for Thought: A Science of Learning in the Classroom. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Greeno, J. G., Collins, A., & Resnick, L. B. (1995). Cognition and Learning. Handbook of Educational Psychology. Hmelo, C. E. (1994). Development of independent learning and thinking: A study of medical problem solving and problem-based learning. Unpublished Dissertation, Vanderbilt University, Nashville. Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. McCombs, B. L. (1996). Alternative perspectives for motivation. In L. A. Baker, P.; and Reinking, D. (Ed.), Developing Engaged Readers in School and Home communities (pp. 67-87). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Morris, C. D., Bransford, J. D., & Franks, J. J. (1977). Levels of processing versus transfer appropriate processing. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16, 519-533. Schank, R., & Neaman, A. (In Press). Motivation and Failure in Educational Simulation Design. In K. Forbus & P. Feltovich (Eds.), Smart Machines in Education . New York: AAAI Press. Schank, R. C. (1982). Dynamic Memory: A theory of reminding and learning in computers and people. New York: Cambridge University Press. Schank, R., A. Fano, B. Bell, and M. Jona. 1993. The Design of Goal-Based Scenarios. Journal of the Learning Sciences 3:4. 305-345. Schank, R. C. (1999). Dynamic Memory Revisited. New York: Cambridge University Press. Tulving, E., & Thompson, D. M. (1973). Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory. Psychological Review, 80, 352-373.