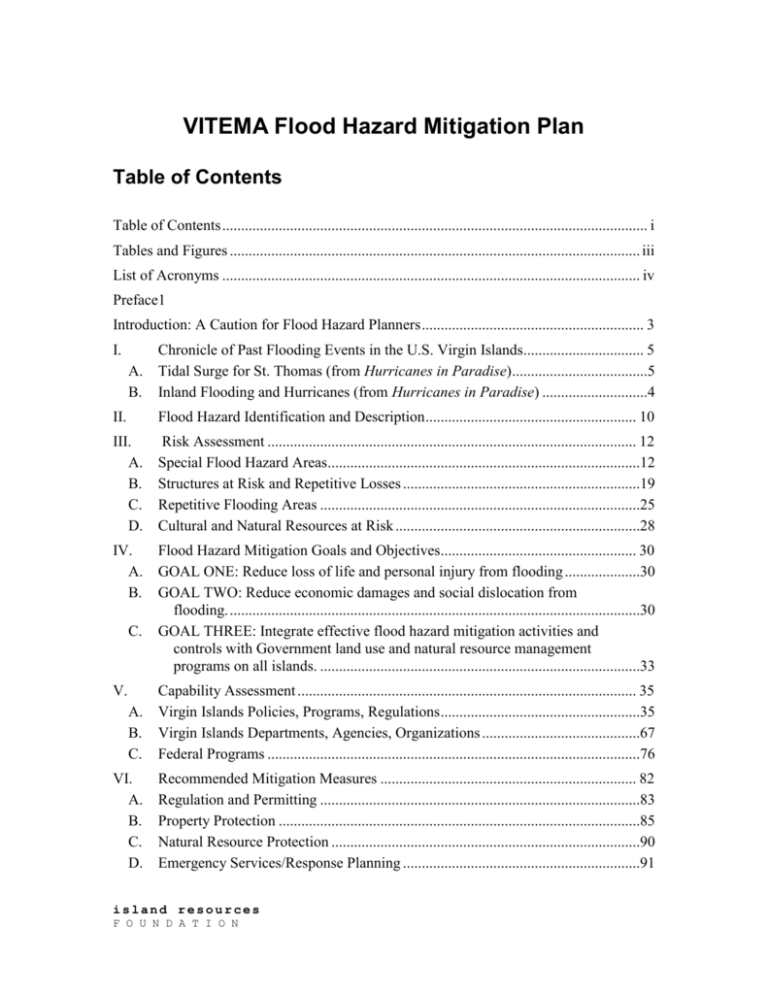

VITEMA Flood Hazard Mitigation Plan

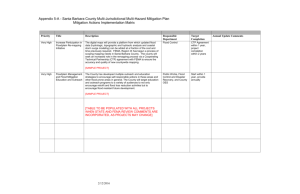

advertisement