Best Practice in Postgraduate Supervision – Literature and Current

advertisement

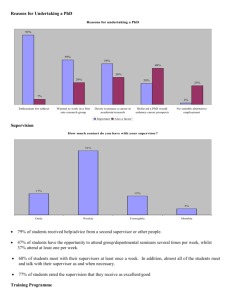

Best Practice in Postgraduate Supervision – Literature and Current College Guidelines - a Discussion Document Dr. David Delany, CAPSL delanydi@mee.tcd.ie on behalf of the Trinity Postgraduate Supervision Research Group Introduction and Purpose Following a literature review designed to illuminate the major issues influencing effective PhD supervision, it was agreed that a useful starting point for relating this literature to current practice in TCD would be to map the current TCD postgraduate supervisor guidelines onto issues identified in the literature. This document reviews the TCD good practice guidelines for postgraduate supervision in the context of the research literature on postgraduate supervision with two key goals in mind: (i) to identify whether the current college guidelines are a comprehensive summary of good practice based on evidence within the rapidly extending literature base on postgraduate supervision. (ii) to create the starting point for the working group to collaboratively develop a supervisor-supervisee survey instrument that could be used internally (or more widely) to explore supervision as enacted in practice. This document comprises a summary comparison of the good practice guidelines and the current literature base. In-text citations are used to compactly indicate literature support for key elements of the good practice guidelines (although, were useful these reference points are elaborated). This is followed by a table of key concepts, as bullet points, derived from the literature review on effective supervision that are addressed (or not) within the TCD guidelines. Further columns and rows in the Table are presented as blank spaces to encourage comments and questions . TCD Postgraduate supervision guidelines The Trinity College Dublin’s postgraduate supervision guidelines (Parnell and Prendergast, 2006) constitute the culmination of TCD’s research supervision best practice recommendations for academic staff and students. Originally written by Prof. John Parnell in 1998, the guidelines have undergone at least two subsequent revisions (in 2005 and 2006) under the deanery of Prof. Patrick Prendergast. Within the guidelines the relationship of the supervisor to the student is considered under four headings: Supervision of research Student training and development Monitoring student welfare Supervisory competence These sections are prefaced by a general introductory section in which the supervisorsupervisee relationship is defined as ideally a mentoring or apprenticeship relationship between partners (Hasrati, 2005; Down et al., 2000; Elton and Pope, 1989). Although the importance of establishing a trusting, secure relationship is emphasised (Green, 2005), potential problems with the mentoring model, such as the masking of the power relationship between student and supervisor (Manathunga, 2007), are not addressed. However, the impact of the perception that students commonly have of themselves as being on the power-receiving end of the supervisor-student relationship is explicitly addressed in the guideline’s final section (Dinham and Scott, 1999). The broad categories of patronage that the supervisor is expected to provide (e.g. consultation, advice, and resources such as material, equipment, etc) are also touched upon, along with indications as to desirable characteristics of such support as accessibility, regularity, and timeliness (Manathunga, 2005). Although the role of the supervisor as ‘gatekeeper’ of academic standards is mentioned (Manathunga, 2007), the guidelines emphasis that the student is ultimately responsible for their own work (Connell, 1985). (i) Supervision of research In this section aspects of the role of the supervisor as a competent academic guide are explored (Haksever and Manisali, 2000; Edwards, 2002). These duties are considered to include guiding research topic choice, matching student abilities/experience to project (Hockey, 1994), determining the feasibility of project with available time and resources, and helping to devise a plausible research plan. An important aspect of this process is helping the student to flexibly (avoid unprofitable/pursue lucrative) side-tracks and avert premature canalization of the research question (Haksever and Manisali, 2000). Constructive and prompt commentary on oral and written work (Torrance et al., 1994), and the use of progress reports (Gurr, 2001), and formal assessment procedures (Li and Seale, 2007) are also flagged as important processes for monitoring of student progress. (ii) Student training and development As depicted in the guidelines, effective student training and development constitutes a balancing act between three main factors: basic regulatory competence in the workplace (i.e. compliance with the relevant regulations, laws and ordinances), academic presentation (Kamler and Thomson, 2004) and teaching skills, and depth of scholarship (which includes the ability to create well-designed experiments) (Cryer, 1997, ChenevixTrench, 2006). (iii) Monitoring student welfare The guidelines assert that the supervisor’s responsibility for student welfare starts with ensuring clear communications with the student (Edwards, 2002, Manathunga, 2005). This is facilitated by ensuring that students are aware of their rights. Abdelhafez (2007), for example, found a positive correlation between student completion probabilities and knowledge of their college’s code of supervisory practice. Supervisors are also advised to be wary of assuming responsibility for student problems that are beyond their personal limitations and are urged to become familiar with the various institutional support structures available to students, such as student counselling services, etc (Manathunga, 2005; Conrad, 2003; Elton and Pope, 1989). Missing from the guidelines is a pragmatic emphasis on the relative importance of awareness of the various factors influencing PhD completion (Manathunga, 2005; Ehrenberg et al., 2007; Gurr, 2001; Lovitts and Nelson, 2000; Seagram et al., 1998). (iv) Supervisory competence The supervisory competence section addresses the importance of basic management aspects of supervision such as time management (Woodward, 1993) and project management skills, such as budgeting sufficient time for students and milestones (Yeatman, 1995), establishing clear lines of responsibility (Abdelhafez, 2007), and managing student over-reliance/dependence (Kam, 1997). The fundamental importance of basic academic competence to effective supervision is also mentioned (Ferman, 2002). The final piece of advice reiterates the central role of communication skills to managing the supervision process (Kam, 1997). Other issues Perhaps surprisingly, despite the emphasis within the guidelines on helping students develop ‘competent autonomy’ (Gurr, 2001) the influence of the supervisor’s characteristics on the quality of the supervisory relationship (Cullen et al., 1994) are not touched upon. The level of systematic reflective upskilling of supervisor skills (Manathunga, 2005; Pearson and Kayrooz, 2004; Emilsson and Johnsson, 2007) is one such issue. This omission is especially surprising given the opportunities for continuing professional development for research supervisors within TCD e.g. CAPSL’s research supervisors workshop. The issue of supervision of supervisors is also unaddressed (Emilsson and Johnsson, 2007). There is also a lack of emphasis on the relative empirical likelihood/importance of the various supervisory issues. For example, Seagram et al., (1998) report that 30% of the variance in time to completion is accounted for by four factors: beginning the dissertation research early in the program, remaining with the original topic and supervisor, meeting frequently with supervisor, and collaborating with the supervisor on conference papers. Furthermore, no mention is made of discipline-specific aspects of postgraduate supervision, such as the notable differences in PhD completion rates between the humanities and sciences (Seagram et al., 1998; Wright and Byrne, 2000; Ehrenberg et al., 2007). Table Mapping Key Concepts of Effective Supervision Practice from the Literature to the TCD Guidelines (presence + and absence -) . PREREQUISITES + Relevant expertise (academic competence) (Phillips and Pugh, 2000) - PhD (Edwards, 2002) RELATIONSHIP + Mentorship/apprentice (Hasrati, 2005; Down et al., 2000; Elton and Pope, 1989) + Secure, trusting (Green, 2005; Fraser and Mathews, 1999) - Potential problems with mentoring model e.g masking of power relationship (Manathunga, 2007) ASSISTANCE - Consultation, advice, resources e.g. material, equipment, etc (Edwards, 2002) - Supervisor accessibility, regularity of meetings, speed of feedback (Woodward, 1993) SUPERVISION of RESEARCH + Guiding research topic choice (Cryer, 1997) + Feasibility of project with available + Drawing up research plan + Matching student abilities/experience to project (Hockey, 1994) + Guiding progress of research [side-tracking, canalisation] (Haksever and Manisali, 2000) + Provision of resources Monitoring student progress: + Commenting on oral & written work constructively & promptly (Torrance et al., 1994) + Progress reports, formal assessment procedures, safety concerns (Li and Seale, 2007) STUDENT TRAINING & DEVELOPMENT + Training process: thesis (training, presentation, depth of scholarship) (Cryer, 1997) STUDENT WELFARE DUTIES + Clear communications (Edwards, 2002, Manathunga, 2005) + Inform students of rights (Abdelhafez, 2007) + Know institutional support structures (Manathunga, 2005; Conrad, 2003; Elton and Pope, 1989) - Pragmatic awareness of factors influencing PhD completion (Manathunga, 2005; Ehrenberg et al., 2007; Lovitts and Nelson, 2000; Seagram et al., 1998; D'Andrea, 2002) SUPERVISORY COMPETENCE + Time management (Woodward, 1993) + Academic competence (Ferman, 2002) + Project management - clear timetable & milestones (Yeatman, 1995) + Clear lines of responsibility (Abdelhafez, 2007) + Handling student over-reliance/dependence (Kam, 1997; Scevak et al., 2007) - Supervisor characteristics (Cullen et al., 1994) - Reflexive upskilling of supervisory skills (Manathunga, 2005; Pearson and Kayrooz, 2004) - Disipline differences (Seagram et al., 1998; Wright and Byrne, 2000) SUPERVISORY SUPERVISION - Supervision of supervisors (Emilsson and Johnsson, 2007) References Chenevix-Trench, G. (2006). What makes a good PhD student? Nature, 441, 252. Connell, R. W. (1985). How to Supervise a Ph.D. Vestes, 28(2), 38-42. Conrad, L. M. (2003). Five Ways of Enhancing the Postgraduate Community: Student Perceptions of Effective Supervision and Support. Retrieved May 27, 2008, from http://surveys.canterbury.ac.nz/herdsa03/pdfsref/Y1033.pdf Cryer, P. (1997). Helping students to identify and capitalise on the skills which they develop naturally in the process of their research development programs. In P. Cryer (Ed.), Developing postgraduate key skills: Issues in postgraduate supervision, teaching and management: A series of consultative guides No 3 (pp. 1013). London: Society for Research in Higher Education. D'Andrea, L. M. (2002). Obstacles to completion of the doctoral degree in Colleges of Education: The professors’ perspective. Educational Research Quarterly, 25(3), 42-58. Dinham, S., & Scott, C. (1999). The Doctorate: Talking about the Degree. Sydney, Australia: University of Western Sydney. Down, C., Martin, E., & Bricknell, L. (2000). Student Focused Postgraduate Supervision A Mentoring Approach To Supervising Postgraduate Students (Version 1). Melbourne: RMIT University. Edwards, B. (2002). Postgraduate supervision: Is having a PhD enough? In Australian Association for Research in Education Conference. Brisbane, Australia. Ehrenberg, R. G., Jakubson, G. H., Groen, J. A., So, E., & Price, J. (2007). Inside the Black Box of Doctoral Education: What Program Characteristics Influence Doctoral Students' Attrition and Graduation Probabilities? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 29(2), 134-150. Elton, L., & Pope, M. (1989). Research Supervision: The Value of Collegiality. Cambridge Journal of Education, 19(3), 267-76. Emilsson, U. M., & Johnsson, E. (2007). Supervision of Supervisors: On Developing Supervision in Postgraduate Education. Higher Education Research and Development, 26(2), 163-179. Ferman, T. (2002). The knowledge needs of doctoral supervisors. Retrieved April 3, 2008, from http://www.aare.edu.au/02pap/fer02251.htm. Fraser, R., & Mathews, A. (1999). An evaluation of the desirable characteristics of a supervisor. Australian Universities' Review, 42(1), 5-7. Green, B. (2005). Unfinished business: subjectivity and supervision. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(2), 151. Gurr, G. M. (2001). Negotiating the "Rackety Bridge" — a Dynamic Model for Aligning Supervisory Style with Research Student Development. Higher Education Research & Development, 20(1), 81. Haksever, A. M., & Manisali, E. (2000). Assessing Supervision Requirements of PhD Students: The Case of Construction Management and Engineering in the U.K. European Journal of Engineering Education, 25(1), 19-32. Hasrati, M. (2005). Legitimate peripheral participation and supervising Ph.D. students. Studies in Higher Education, 30(5), 557. Hockey, J. (1994). New Territory: Problems of Adjusting to the First Year of a Social Science PhD. Studies in Higher Education, 19(2), 177-90. Kam, H. (1997). Style and quality in research supervision: the supervisor dependency factor. Higher Education, 34(1), 81-103. Kamler, B., & Thomson, P. (2004). Driven to Abstraction: Doctoral Supervision and Writing Pedagogies. Teaching in Higher Education, 9(2), 195-209. Knowles, S. (1999). Feedback on Writing in Postgraduate Supervision: Echoes in Response-Context, Continuity and Resonance. Supervision of Postgraduate Research in Education, 113-128. Li, S., & Seale, C. (2007). Managing criticism in Ph.D. supervision: a qualitative case study. Studies in Higher Education, 32(4), 511. Lovitts, B. E., & Nelson, C. (2000). The Hidden Crisis in Graduate Education: Attrition from Ph.D. Programs. Academe, 86(6), 44-50. Manathunga, C. (2005). Early Warning Signs in Postgraduate Research Education: A Different Approach to Ensuring Timely Completions. Teaching in Higher Education, 10(2), 219-233. Manathunga, C. (2007). Supervision as Mentoring: The Role of Power and Boundary Crossing. Studies in Continuing Education, 29(2), 207-221. Parnell, J., & Prendergast, P. J. (2006). Postgraduate Supervision: Best Practice Guidelines On Research Supervision For Academic Staff and Students. Retrieved May 27, 2008, from http://www.tcd.ie/Graduate_Studies/docs/Supervison%20Guidelines.pdf. Pearson, M., & Kayrooz, C. (2004). Enabling critical reflection on research supervisory practice. International Journal for Academic Development, 9(1), 99. Phillips, E., & Pugh, D. (2000). How to Get a PhD: A Handbook for Students and Their Supervisors (3rd ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press. Seagram, B. C., Gould, J., & Pyke, S. W. (1998). An Investigation of Gender and Other Variables on Time to Completion of Doctoral Degrees. Research in Higher Education, 39(3), 319-35. Wisker, G., Exley, K., Antoniou, M., & Ridley, P. (2006). Working One-to-one with Students: Supervising, Coaching, Mentoring, and Personal Tutoring, Routledge. Woodward, R. J. (1993). Factors affecting research student completion. Presented at the 15th annual forum of the European Association for Institutional Research. Turhu, Finland. Wright, T., & Byrne, R. M. J. (2000). Factors Influencing Successful Submission of PhD Theses. Studies in Higher Education, 25(2), 181-195. Yeatman, A. (1995). Making Supervision Relationships Accountable: Graduate Student Logs. Australian Universities' Review, 38(2), 9-11.