A Survey - American Industrial Hygiene Association

advertisement

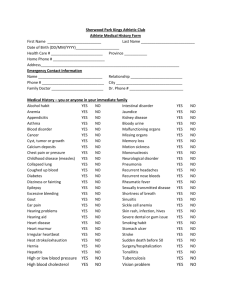

A Survey of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Complaints among Dental Hygienists in Kentucky. RaeAnne Szeluga, MSPH University of Kentucky, Preventive Medicine and Environmental Health 1141 Red Mile Rd, Ste 102, Lexington, KY 40504 Introduction and Background Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) plague the nation’s workforce and have become the focus of study in occupational investigations. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders arise from normal work activities that become hazardous when the body is not permitted proper rest periods among other considerations including job task design. Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are defined as a series of micro-traumatic events that accumulate in the body and as a result, develop into a more severe injury to the musculoskeletal system. Risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders include static body positions, highly repetitive motions, mechanical stress or force, and exposure to vibration or cold temperatures. A number of musculoskeletal injuries can be avoided if occupational risk factors are identified and preventive measures are put into place. In the field of dental hygiene, work-related musculoskeletal disorders have only recently been recognized as an occupational hazard. The American Dental Association (ADA) recently acknowledged that dentists and dental hygienists are at risk for work-related musculoskeletal disorders as a result of everyday work activities. The purpose of this study was to describe the characteristics of work-related musculoskeletal complaints among dental hygienists. The following are the specific aims for this study: 1. Identify the prevalence for different anatomic locations of musculoskeletal complaints among dental hygienists surveyed in Kentucky. 2. Examine the association between work practices and demographic characteristics of dental hygienists, and musculoskeletal complaints. 3. Determine if dental hygienists with diagnosed medical conditions or neurological disorders have an increase in musculoskeletal complaints compared to hygienists without previous conditions. 4. Identify whether changes have occurred in daily work practices and personal activities as a result of musculoskeletal complaints. There are currently an estimated 100,000 dental hygienists in the United States, of these 1,550 are in Kentucky. Although there is not an established baseline prevalence estimate for musculoskeletal disorders, one study documents that 93% of a sample population of dental hygienists report at least one symptom of a musculoskeletal disorder. The table below is a compilation of results from recent studies of dental hygienists and shows variables that were found to be significantly associated (p<.05) with the corresponding locations of musculoskeletal complaints. Table 1. Variables Significantly Associated with Corresponding Location of Pain Hours/ week Days/ week Yrs of prac. Body position Neck Ylippa Shoulder Ylippa Osborn Back Osborn Osborn Arms Osborn Ylippa Ylippa Liss Liss CTS Liss Liss Heavy calculus pts/day Prev med cond Min/ patient Ylippa Ylippa Ylippa Liss Ylippa Modify work practice Age Osborn Liss MacDonald Liss Osborn Osborn Methods A descriptive cross-sectional study was used in this research. A small sample of dental hygienists (n=433) served as representatives for the total population of registered dental hygienists in Kentucky (1,550). A complete member list of state-registered dental hygienists was obtained from the Kentucky Dental Hygienists’ Association (KDHA). This study was approved by the University of Kentucky Medical Institutional Review Board (IRB), #9911072. Participation was completely voluntary and there were no personal identifiers. The questionnaire packet was mailed to all 433 registered dental hygienists in the KDHA. The packet included the questionnaire with instructions, letter of support, and a pre-stamped reply envelope. Follow-up reminder postcards listing contact numbers and information were mailed to non-respondents three weeks after the initial mailing. A body diagram was designed specifically for use in the research study questionnaire. The design of the diagram was modeled from NIOSH recommendations. Close-ended questions regarding symptoms of musculoskeletal pain were included with the pre-coded body diagram. Questionnaires used in two major research studies regarding musculoskeletal disorders in dental hygienists were obtained from the authors. Additional questionnaires and information obtained from a review of the literature was also used as a basis for identification of study variables. The independent variables, or predictors, in the study were the work practices and demographic characteristics of the dental hygienists surveyed. Other independent variables examined were the dominant hand of the hygienist, and previously diagnosed medical and neurological conditions. The frequency and severity of pain in a specific body region made up the dependent variables, or outcome measures, for the study. Musculoskeletal complaints were identified defined by the presence or absence of pain in each specific body region. Survey data was entered into Epi Info, Version 6.25 as it was returned. After initial frequency analysis on the data, the complete data set was transferred to SAS for Windows. Descriptive statistics were generated in order to obtain frequency tables for all listed independent variables. Stratified, bivariate analysis (2x2 tables) was performed using odds ratios (OR) to look at the association between potential 2 risk factors (independent variables) and each dependent variable. Some independent variables were categorical, and others were dichotomous. In analyzing categorical variables, a referent group was chosen from the categories. From the bivariate analysis, we screened for risk factors that had elevated odds ratios (greater then 1.5), and included them in a multiple logistic regression analysis for the dependent, outcome variable. Some possible confounders were controlled for through the use of multivariable analysis. A p-value of <.05 is considered significant. Due to the small sample size and high reports of pain in a few areas, only four body regions (neck, shoulder, wrist/hand, and lower back) were examined using logistic regression. Results Data analysis was based on a final sample size of two hundred forty five (N=245). Detailed demographic information and descriptions of work characteristics can been found in Tables 2 and 3. Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of Female Dental Hygienists in Kentucky Demographics Age: 22 - 33 years 34 - 44 years 45 years Years of Practice: 1-3 years 4-9 years 10-15 years 16 years BMI: < 20 kg/m2 (underweight) 20 - 24.9 kg/m2 (normal) 25 - 29.9 kg/m2 (overweight) 30 kg/m2 (obese) n % 81 93 70 33.2 38.1 28.7 75 52 37 81 30.6 21.2 15.1 33.1 31 141 52 21 12.6 57.6 21.2 8.6 Table 3. Characteristics of the Work Exposure Patterns for Dental Hygienists N Median Range Days/week 243 4 days 1-5 days Hours/day 231 8 hours 3-14 hours Patients/day 240 9 patients 2-25 patients Minutes with each patient 245 45 minutes 15-70 minutes Minutes in between patients 211 5 minutes 1-45 minutes Minutes in twisted, rotated 235 20 minutes 1-60 minutes position with each patient Minutes bent forward with each patient 236 20 minutes 0-50 minutes Cumulative Work Hours Tools used with patients: Handpiece (# patients/day) Ultrasonic (# patients/day) Scalers (# patients/day) 239 6.3 hours 1.8 – 11.3 hours 242 214 243 8 patients 3 patients 8 patients 1-25 patients 1-20 patients 1-15 patients 3 Table 4 addresses the self-reported prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in the sample population. Ninety six percent of the dental hygiene participants in this survey (n=234; 96%) reported musculoskeletal pain. The four body regions with the highest frequency of pain reported are the neck, wrist/hand, lower back, and shoulder. Table 4. Self-Reported Prevalence (%) of Musculoskeletal Complaints Among Kentucky Dental Hygienists (N=245), 1999 Body Part n % 95% CI Neck Shoulder Upper Back Lower Back Elbow Forearm Hip Wrist/Hand Upper Leg Knee Lower Leg Ankle 203 186 148 193 51 84 85 196 33 59 26 55 82.6 75.9 60.4 78.8 20.8 34.3 34.7 80.0 13.5 24.1 10.6 22.4 77.4 - 87.2 70.0 - 81.0 54.0 - 66.5 73.0 - 83.6 16.0 - 26.6 28.4 - 40.6 28.8 - 41.1 74.3 - 84.7 9.6 - 18.5 19.0 - 30.0 7.2 - 15.3 17.5 - 28.3 % Reporting 1 days missed from work 5.4 5.9 2.7 5.7 3.9 4.8 4.7 4.6 6.1 1.7 3.8 7.3 Approximately forty one percent of the hygienists (n=99; 41%) reported they have modified their work activities and practices because of discomfort, pain, tingling, or numbness. In addition, twenty seven percent of the sample (n=66; 27%) modified their daily household activities and thirty two percent (n=78; 32%) modified their leisure activities due to musculoskeletal pain. Other prevention efforts have been made by the hygienists; a complete list is documented in Table 5. Table 5. Measures taken by Dental Hygienists to prevent injury or reduce discomfort, pain, tingling, or numbness. Preventive Measures Stretching Improved posture Lumbar or chair supports Proper fitting gloves Workstation adjustment More frequent breaks Reduced work hours Altering work schedule Ergonomic instruments Personal relaxation or meditation Prescription medication Over-the-counter medication Bandage or brace (not prescribed) Chiropractor (N=245) n 168 175 24 117 54 26 42 20 57 54 36 113 37 16 4 Hygienists % 68.6 71.4 9.8 47.8 22.0 10.6 17.1 8.2 23.3 22.0 14.7 46.1 15.1 6.5 The dental hygienists indicated the most severe and frequent reports of pain, discomfort, tingling, or numbness in their neck, shoulders, lower back, and wrist/hand. These four body regions were examined in greater detail. Table 6 summarizes the statistically significant risk factors and protective findings from the documented literature compared to this research study for the neck, shoulders, back, and wrist/hand regions. Table 6. Comparison of Risk Factors (-) and Protective Findings (+) Previous Research Literature Current UK Dental Hygiene Study Neck Shoulders Back Wrist/Hand - Hours per week - Body position - Minutes with patient - Hours per week - Days worked per week - - # yrs practicing DH - Body position - Minutes with patient - Hours per week - # yrs practicing DH - Age - # yrs practicing DH - Body position - Heavy calculus patients - Previous medical cond. - Minutes bent forward over patient + 6-10 minutes b/n patients - Minutes in a twisted/rotated body position - Minutes in a twisted/rotated body position - Minutes bent forward over patient + Age (≥ 41 yrs) + Working 5 days per week NOTE: p < 0.05 for all factors listed Conclusions In this study, 96% (n=234) of the respondents indicated experiencing musculoskeletal pain over the past twelve months. Within the sample population, only eleven individuals were free from pain. The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain estimated in this study was higher than reports from other studies. A major limitation of this study is the reliance on an individual’s willingness to disclose personal and health related information. All participants were made aware that the survey was confidential and data was reported at the group level only. This study also had the potential for recall bias because it is asked participants to remember musculoskeletal complaints and information regarding the past year. The participants who experienced pain may be more likely to remember events and volunteer that information, which leads to response bias. Stress and dissatisfaction with employment was not addressed in this survey; however, it can influence the amount of discomfort a person experiences in their job. The dental hygiene profession requires extensive training and education. Dental hygienists often work on a strict time schedule and have a very regular routine. It is easy to recognize that the more difficult and heavy calculus patients will require more time and more labor. As a result, the dental hygienists do not work with hundreds of patients each week and each week often resembles the previous one. The 5 hygienists are a good population to answer surveys because they are very aware of their regular work routines and hazards. In almost every body region examined, awkward body positions proved to provide the greatest risk for pain. By educating the hygienists of MSDs and promoting the use of ergonomic chairs and instruments, it is possible to alleviate some of the risks and pain associated with awkward body positions. In some cases, the younger hygienists were more at risk for pain then the older hygienists. The older hygienists may have good methods of preventing pain in work and leisure activities. Also, the older hygienists may no longer be clinically practicing dental hygiene, or are working strictly as educators in the field. The risks and hazards of the job may have forced them into other fields or retiring; therefore, it would appear to have a healthy worker effect. Although, statistical significance was not widely demonstrated in the sample, the fact remains that this is a population of individuals who are routinely experiencing pain from work activities. These findings illustrate the clinical relevance of the study. In examining changes made by the hygienists, as addressed in the specific aims of the study, it was shown that the hygienists are making attempts to prevent injuries in their daily work activities. The majority of the sample population reported actively trying to reduce their risk for injuries by modifying work, leisure, and household activities that were painful. The prevention efforts may be drastically reducing serious musculoskeletal injuries and reports of severe and frequent pain. The demographic information of the dental hygienists in Kentucky had not been examined until this study. With the documented prevalence of musculoskeletal pain for each body region, prevention efforts may now be more focused and can be addressed. This research project will be taken into consideration by the KDHA not only for demographic information but to help prevent future injuries in dental hygienists. References 1. Fredekind R, Cuny E. Instruments used in dentistry. In: Murphy, DC (Ed), Ergonomics and the Dental Care Worker. Washington DC: American Public Health Association. 1998:169-189. 2. Putz-Anderson V. Cumulative trauma disorders: a manual for musculoskeletal disease of the upper limbs. Philadelphia PA: NIOSH/Taylor and Francis. 1988. 3. Atwood MJ, Michalak C. The occurrence of cumulative trauma in dental hygienists. Work. 1992;2(4):17-31. 4. Kroemer KHE. Avoiding cumulative trauma disorders in shops and offices. Am Ind Hyg J. 1992;53(9):596-604. 5. Haslegrave CM. What do we mean by a ‘working posture’?. Ergonomics. 1994;37(4):781-799. 6. Barry RM, Woodall WR, Mahan JM. Postural changes in dental hygienists: four-year longitudinal study. J Dent Hyg. 1992;66(3):147-150. 7. Liskiewicz ST, Kerschbaum WE. Cumulative trauma disorders: an ergonomic approach for prevention. J Dent Hyg. 1997;71(4):162-167. 8. Punnett L, Robins JM, Wegman DH, Keyserling WM. Soft tissue disorders in the upper limbs of female garment workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1985;11:417-425. 9. Silverstein BA, Fine LJ, Armstrong TJ. Occupational factors and carpal tunnel syndrome. Am J Ind Med. 1987;11:343-358. 10. MacDonald G, Robertson MM, Erickson JA. Carpal tunnel syndrome among California dental hygienists. Dent Hyg. 1988;62:322-328. 6 11. Stentz TL, Riley MW, Harn SD, et al. Upper extremity altered sensations in dental hygienists. Int J Ind Ergonomics. 1994;13:107-112. 12. Oberg T. Ergonomic evaluation and construction of a reference workplace in dental hygiene: a case study. J Dent Hyg. 1993;67(5):262-267. 13. Ylippa V, Arnetz BB, Benko SS, Ryden H. Physical and psychosocial work environments among Swedish dental hygienists: risk indicators for musculoskeletal complaints. Swed Dent J. 1997;21(3):111-120. 14. Oberg T, Karsznia A, Sandsjo L, Kadefors R. Work load, fatigue, and pause patterns in clinical dental hygiene. J Dent Hyg. 1995;69(5):223-229. 15. Osborn JB, Newell KJ, Rudney JD, Stoltenberg JL. Musculoskeletal pain among Minnesota dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 1990;63:132-138. 16. Oberg T, Oberg U. Musculoskeletal complaints in dental hygiene: a survey study from a Swedish county. J Dent Hyg. 1993;67(5):257-261. 17. Liss GM, Jesin E, Kusiak RA, White P. Musculoskeletal problems among Ontario dental hygienists. Am J Ind Med. 1995;28(4):521-540. 18. Guay AH. The American Dental Association and dental ergonomics: research, observations, and activities. In: Murphy, DC (Ed), Ergonomics and the dental care worker. Washington DC: American Public Health Association.1998: 417-442. 19. American Dental Hygienists Association (On-line). Dental Hygiene Statistics. http://www.adha.org/faqs/index.html. 20. American Dental Association (On-line). ADA Fact Sheets. http://www.ada.org/prac/careers/fs-html. 21. Osborn JB, Newell KJ, Rudney JD, Stoltenberg JL. Carpal tunnel syndrome among Minnesota dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 1990;65:79-85. 22. Aday LA. Designing and Conducting Health Surveys. San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass. 1989. 23. Cohen AL, Gjessing CG, Fine LJ, et al. Elements of ergonomic programs: A primer based on workplace evaluations of musculoskeletal disorders. DHHS(NIOSH) Publication No. 97-117. Cincinnati OH: DHHS/PHS/CDC/NIOSH. 1997. 24. Wolens D. The predictive ability of instrumentation for screening and surveillance of carpal tunnel syndrome. In: Kasdan ML (Ed), Occupational hand and upper extremity injuries and diseases, 2 nd Edition. Philadelphia PA: Hanley and Belfus, Inc. 1998: 141-148. 25. Bessette L, Keller RB, Lew RA, et al. Prognostic value of a hand symptom diagram in surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Rheumat. 1997;24(4):726-734. 26. Katz JN, Stirrat CR, Larson MG, et al. A self-administered hand symptom diagram for the diagnosis and epidemiologic study of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Rheumat. 1990;17(11):1495-1498. 27. Sanders MJ, Turcotte CA. Ergonomic strategies for dental professionals. Work. 1997;8:55-72. 7