Previously published in Northwest Anthropological Research Notes, 31(1-2):71-95 (1997)

THE YAKAMA SYSTEM OF TRADE AND EXCHANGE

DEWARD E. WALKER, JR.

Abstract

The anthropological and other research concerning the prehistoric, protohistoric, and historic

patterns of trade and exchange of the Yakama and neighboring tribal groups is summarized. An

extensive system of trade and exchange extending from the Plains and Great Basin to the Plateau

and Northwest Coast is described. This was the preexisting basis for the Hudson's Bay

Company's system of trade and exchange, and it functioned both in parallel and as part of the fur

trade system. Access to this complex network of interrelated trade centers was essential to

maintenance of the Yakama traditional economy and way of life. As further evidence, Governor

Stevens gave repeated assurances during treaty negotiations in 1855 that the Yakama and certain

other tribes were to retain their traditional rights of access to this system. There can be little

doubt that the Yakama enjoyed off-reservation travel as an essential part of their economy and

way of life both before and after 1855.

Introduction

The evidence presented here provides the basis from which further exploration of the complex

interdependencies of Plateau and other tribes of the Northwest may be investigated. Tribally

focused research approaches continue to obscure the systematic nature of patterns of trade and

exchange in the regions. There is a need for more research focused above the tribal level

following the examples of Walker (1967), Anastasio (1972), Stern (1993), and others. The

apparent uniqueness of many groups described by ethnographers tends to disappear in this larger

analytic framework. In one sense, differences have tended to overwhelm similarities and

interconnections in much of the previous anthropological research in the Plateau and neighboring

culture areas. Likewise, obvious similarities and interconnections among culture areas have been

ignored or overlooked in our zeal to defend research domains.

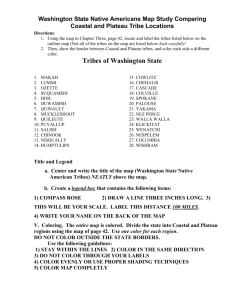

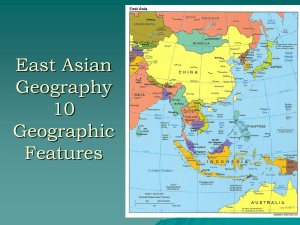

Following Anastasio (1972), Chance (1973), Stern (1993), and others, four maps (Figs. 1-4) have

been prepared which contain information regarding tribal trade centers and networks of the

Northwest, with depiction of the Hudson's Bay Company operations in the Columbia region.

These maps help depict the nature and extent of the traditional system of trade and exchange in

which the Yakama have, and continue to be, primary players linking the Plains, Plateau, Great

Basin, and Northwest Coast areas. These maps also depict the two Hudson's Bay Company

(HBC) districts&endash;Nez Percés and Colvile&endash;where HBC fur traders engaged in

trade and exchange with Plateau tribes over several decades before 1846 after which time the U.

S. acquired the Oregon Territory. These districts, trading posts, and trade networks reflect

Prehistory

Sahaptian peoples appear to have occupied the Columbia Plateau for more than 10,000 years

(Leonhardy and Rice 1970:4; Daugherty 1973:4). The site at Five Mile Rapids in the Long

Narrows of The Dalles indicates continuous occupation from 7500 B.C. (Cressman and others

1960; Strong 1961). A large site at Goldendale, twenty miles to the northeast, has also been

dated to this general period by Warren (1968), and another large site in the same area was dated

at 5800 B.C. by Warren, Bryan, and Tuohy (1963). The evidence from historical linguistics and

oral history also support an original settlement of the area by Sahaptian speakers who all lack

migration tales. Not one myth in the extensive corpus of Sahaptian myths and legends that have

been collected since the middle of the nineteenth century indicates that they originated elsewhere

than in the Columbia Basin (Beavert and Walker 1974; Aoki and Walker 1989).

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Plateau way of life has remained fundamentally the

same for at least ten thousand years prior to the first Euroamerican influences of the eighteenth

century. What demonstrable changes did occur during this period of time can be traced to either

climatic change or to innovation in techniques. By 9000 B.P., rich archaeological deposits occur

throughout the Columbia Plateau from The Dalles, east to the Snake River at Windust Cave and

Hell's Canyon (Kirk and Daugherty 1978; Ames and Marshall 1981), north to Kettle Falls, and

west to the Fraser River canyon. These early Plateau peoples harvested fish, including salmon

and suckers (Ames and Marshall 1981:41), gathered plant foods in large quantities, hunted large

ungulates, and traded with coastal peoples for decorative shells (Kirk and Daugherty 1978:37;

Erickson 1990). Excavations near The Dalles have disclosed large quantities of salmon bones.

Ames and Marshall (1981:41) note that though fishing tackle and fish remains are generally rare

in southeastern Plateau sites, they are present throughout the regional sequence. Kettle Falls

archaeology reveals evidence of fishing as early as 9000 B.P. (Kirk and Daugherty 1978:67).

Nelson (1969) in his Salish-expansion theory asserts that the ancestral Salish brought intensive

fishing with them and helped produce the Plateau winter village settlement pattern. He says the

Salish expansion originated in the Fraser delta about 4500 B.P. at the end of the Altithermal

(Elmendorf 1965). Ames and Marshall (1981:43, 47) dispute this theory, arguing that pit-house

villages first appear by 5000 B.P. in the southeastern part of the Plateau, far from the center of

Salish expansion. Somewhat unconvincingly, they ascribe this new residential pattern not to

improved fishing techniques imported from the coast, but to an increased intensity of root

collection which emphasized a preexisting Plateau subsistence focus. Kirk and Daugherty

(1978:67) suggest that roots, berries, and greens have been major foods from the earliest times

and that the Marmes deposits bear this out.

They also conclude that culture change in the Plateau proceeded at a modest pace through

various millennia to historic time. For example, Kirk and Daugherty (1978:68) say that if

projectile points are:

arranged by age . . . [they] show a progression in form and manufacturing

technique, not necessarily an improvement through time&endash;for early

workmanship was as good as what came later&endash;but a definite and ordered

change. Points became gradually smaller . . . reflecting the change in weaponry

from spears that were thrust to those thrown with atlatls, and finally to bows and

arrows.

Protohistory

One of the most dramatic shifts in Plateau history is stimulated by adoption of the horse after

A.D. 1700. The Yakama quickly learned to ride and to geld their stallions (Osborne 1955) and to

control both the behavior and the genetics of their herds. They acquired wealth in horses by the

thousands. Francis Haines has traced the spread of horses from their source in the Spanish

colonies of the Southwest. In 1860, horses spread up both sides of the Rockies from Apaches to

Comanches, from Pawnees to Kansas Indians, reaching the upper Missouri by 1740. On the west

they spread from the Ute on the Colorado Plateau to the Shoshone of the Upper Snake, then to

the Flathead by 1720 and on to the Nez Perce and Cayuse sometime after 1730.

The horse was adopted quickly and became an integral part of Plateau and Yakama life. It did

much to intensify existing patterns of subsistence, trade, and exchange, broadening the range of

Yakama travel by several orders of magnitude. Raiding became a problem as well. Lewis and

Clark noted that the Columbia River villages from the Umatilla to The Dalles were mostly

located on the north shore or on islands in the stream, for fear of the depredations of Shoshone,

Paiute, and Bannock raiders. They had adopted horses earlier and a wide-ranging predatory life

style, hunting bison in the headwaters of the Snake, Missouri, and Yellowstone rivers. The early

Shoshone-Bannock traveled east of the continental divide and warred with Blackfeet and Siouan

groups. Not long after horses enlarged the scope of intergroup raiding, fur traders began

extending their frontier outposts toward the eastern base of the Rockies. The new pattern of

warfare, while a dramatic innovation, probably had little effect on the basic ecological relations

of people and resources along the mid-Columbia River. Bison hunting did substantially increase.

Horses soon became accepted as standards of wealth, movable wealth that needed only to be set

loose to feed on the nutritious range grasses, abundant on the low plains and into the mountains.

The new life widely prophesied and promised by the coming of the whites brought many

changes (Walker 1969). The first recorded epidemics came about 1775. Robert Boyd (1985:8190) believes that the first wave of smallpox came from the west about 1775 from ships exploring

for furs along the north Pacific coast, rather than up the Missouri. My own research before Boyd

confirms this hypothesis. Smallpox ravaged the Columbia River area (Boyd 1985:99-100),

reducing the original population to about one half by the time of Lewis and Clark's exploration.

In their journals, Lewis and Clark describe old men with pockmarked faces among the Upper

Chinooks of the lower Columbia River and were told that the disease had struck a generation

before, essentially eliminating the vast Chinookan system of trade and commerce centered on the

lower Columbia River (Thwaites 1904-05). Asa Bowen Smith documents its ravages among the

Nez Perce at about the same time (Drury 1958:136). An outbreak of the disease was reported in

1824-25 (Boyd 1985:338-341). The epidemic of 1853 was documented in detail by McClellan

(1855) of the railroad survey party as they conducted their explorations for a trans-Cascades rail

route.

The "fever and ague" (probably malaria) that broke out at the Hudson's Bay Company's Fort

Vancouver headquarters in the summer of 1830 (Cook 1955; Boyd 1985:112-145) raged

unchecked for four years before abating. It decimated the Chinookan villages of the lower

Columbia and Kalapuya Indian populations throughout the Willamette Valley extending to the

densely settled Central Valley of California. Though spared from malaria, the Plateau people

next found themselves in the path of thousands of immigrants crossing the continent over the

Oregon Trail. Seasonal respiratory diseases had become commonplace among the Indians who

congregated at fur trading posts each winter (Boyd 1985:341-348), a pattern repeated at the

missions. With the immigrants came new diseases against which the Indians had no resistance. In

1844 there was scarlet fever and whooping cough, and in 1846 more scarlet fever (Boyd

1985:349-350).

The Fur Trade

Fur clothing was in demand during the eighteenth century, especially in the Orient. The Hudson's

Bay Company claimed the furs from the Arctic to the Mackenzie and the Northwest Coast.

Northwest furs were collected throughout the Columbia drainage basin for shipment to China.

There they were exchanged for rare spices, silks, and tea for resale in New York and Boston and

thus the Americans became known as "Boston men."

Neither the Colvile nor the Nez Perce district ever proved a great producer of furs. In part this

may be attributed to the fact that a good fraction of the territory is not forested and supported

relatively few fur bearers. Equally significant is the fact that most Plateau peoples were simply

not interested in trapping furs for trade (Simpson 1931:42, 54); for example the Nez Perce

considered it beneath their dignity. Following the 1818 agreement between Britain and the

United States to share the Oregon country, the Northwest Company embarked on an aggressive

Snake River strategy designed to deny that region's furs to the Americans (Simpson 1931:46).

"Brigades" of trappers (not local Indians) were provisioned each summer at Astoria and packed

their provisions up the Columbia to Walla Walla by canoe, then loaded their goods on horseback

for the overland passage to the upper Snake where they engaged in intensive trapping, returning

with their furs to Astoria (or Fort Vancouver) in June of the following year.

The Plateau Indians' role in this operation was more that of spectator than participant, though

they were essential sources of horses used by the overland brigades

and&endash;curiously&endash;they were major providers of venison for fur company personnel.

The Columbia River was the main link in these commercial chains and Fort Nez

Percés&endash;established at the mouth of the Walla Walla River by Donald McKenzie in July

of 1818&endash;eventually became the nerve center of the entire inland operation, located as it

was at the strategic junction of the Snake and Columbia-Fraser shipping routes (Stern 1993). Fort

Nez Percés retained its importance until the 1846 treaty. Indian-fur trader relations were

relatively positive, since the goal of the trade was a profitable business in furs. To that end the

Indians tolerated the traders' presence and were free to pursue their seasonal rounds and

traditional trade and exchange. Traders actively discouraged intergroup warfare as an

impediment to free movement of the trapping brigades (Stern 1993). Marriages between Indian

women and European or Métis trappers had the effect of expanding the Plateau Indian social

network to include individuals of radically different world views. Some twenty Catholic Iroquois

trappers married into Flathead society before 1820 and may have provided them their first

instruction in Christian ritual practice.

The Missionaries

Openness to such intermarriage is shown in Walker's (1972) analysis of Nez Perce outmarriage

as a practice that helped maintain trade and exchange systems. Fur traders were often Christian

and provided impetus for various innovative religious movements (Walker 1969). The fur

traders' resistance to diseases that decimated the tribes was attributed to their spiritual powers

and to the power of their books. Following the Hudson's Bay Company's takeover in 1821 and

Governor Simpson's inspection tour of the Columbia Department in 1825 (Simpson 1931),

several chiefs' sons were brought to the Company's Red River headquarters to be educated in the

English manner. Disease took the lives of most of these young men, but a few returned to

positions of influence. A delegation of four Nez Perce and Flathead young men also traveled

eastward intending to secure missionaries of their own (Haines 1937; Drury 1958:106-107). The

missionary societies responded. The Methodists sent Jason Lee with Nathaniel Wyeth's fur

brigade in 1834. The rival American Board of Committees for Foreign Missions, a joint

Presbyterian, Congregational, and Dutch Reform effort, active in Hawaii since 1820, sent

Samuel Parker and Marcus Whitman in 1835. Whitman returned overland to recruit a permanent

missionary contingent for the following year.

The Whitmans established their mission in Cayuse territory, and the Spaldings moved to Lapwai.

In 1838 Walker and Eells arrived to set up the Tshimakain mission among the Spokans, and the

Methodists sent Perkins to join with Jason and Daniel Lee in founding a station at The Dalles.

Like the Hudson's Bay Company posts, the mission compounds were supported by farming

operations. Self-sufficiency, however, was only a secondary goal of the missionary farmers.

Uppermost in their minds was the goal of transforming their nomadic charges into settled

farmers. The constant travel of the tribes was a great impediment to the missionaries' efforts at

schooling their children and in eradicating cultural practices, such as the polygyny of chiefs and

other influential men. Whitman and Spalding had initial successes, reporting in 1843 that 234

children were in school, 140 Nez Perce were farming wheat, corn, and potatoes at Lapwai, and

60 Cayuses were farming at the Waiilatpu mission (Meinig 1968:136). Perkins and Lee are

credited with 1000 conversions in their great winter revival of 1839-1840 at The Dalles (Perkins

1843). Settled farming life was a radical break from the social and economic patterns of Plateau

peoples, and they soon reverted to their traditional subsistence rounds, leaving the missionaries

with empty pews.

The heyday of this first phase of missionary activity in the Plateau was brief, beginning with

Whitman's and Spalding's arrivals and ending abruptly after the death of the Whitmans in 1847.

Their deaths saw the beginnings of military pacification, forced Indian resettlement on

reservations, and the invasion of many more white settlers. Indian disillusionment with the

missionaries, who had been hailed first as miracle workers was due to several factors (Walker

1968, 1969), such as their association with epidemic disease and the presence of large numbers

of whites. The Nez Perce missionary, Smith, wrote letters revealing a deep skepticism about the

entire Northwest Indian missionary enterprise. Smith was well-educated, trained in Latin and

Greek, and he took the task of learning the native language seriously. He wrote, "without a

knowledge of the language we are useless," and "the difficulty of translation seems almost

insurmountable" (Drury 1958:104, 138). He worried at length over how to faithfully convey the

true meaning of such words as "baptism" (Drury 1958:112). Smith criticized Spalding for

admitting Timothy and Joseph into the church, "without any articles of faith or covenant in their

language and no one able to explain the articles of faith & covenant satisfactorily to them in the

Nez Perce language." Smith believed that they did not know what they were required to believe

(Drury 1958:143). Smith also took issue with Spalding's insistence on converting the tribes to a

settled farming life. He argued correctly that settling them would prevent them from providing

for their own subsistence. Smith departed from the mission field in the spring of 1841. Schuster

(1975) provides a detailed discussion of Yakama missionization.

The Treaty of 1855 and Establishment of the Reservations

Between 1778 and 1871 the government of the United States negotiated and ratified 371 treaties

with tribes of the present United States (Zucker, Hummel, and Hogfoss 1983:69). In 1871,

Congress determined that no treaties would thereafter be negotiated with any Indian tribe within

the United States as an independent nation or as a distinct people. Subsequent Indian reservations

were established and rescinded by executive order as in the case of the Colville, Spokane, and

certain other reservations of the Northwest.

The earlier treaties in the Northwest and elsewhere reflected the balance of power between

sovereign Indian governments and the still-tenuous power of the youthful United States. By the

mid-1800s the balance of power had shifted dramatically, except in the Northwest. Then Federal

Indian Commissioner George Manypenny wrote to Governor Stevens directing him to "enter at

once upon negotiations . . . having for principle [sic] aim the extinguishment of the Indian claims

to the lands . . . so as not to interfere with the settlement of the territories" (Relander 1962:39).

Stevens responded that "the large reserve (i.e., that of the Yakama) is in every respect adapted to

an Indian reservation (Relander 1962:44).

It is instructive to review the wording in the Act of 14 August 1848 (9 Stat. 323) establishing the

Oregon Territory. This Act stated that nothing in it: "shall be construed to impair the rights of

persons or property now pertaining to the Indians in said Territory, so long as such rights remain

unextinguished by treaty between the United States and such Indians."

In an address given at the Walla Walla treaty council ground on Tuesday 5 June 1855, Governor

Stevens (1985) reflected the honorable intent of the Unites States when he stated to the Yakama

and other assembled tribes as follows: "I need say nothing more. It [the Treaty of 1855] is

designed to make the same provision for all the tribes and for each Indian of every tribe. The

people of one tribe are as much the people of the Great Father as the people of another tribe; the

red men are as much his children as the white men."

On the same day, Governor Stevens (1985) explained further the various provisions that were

being proposed for all the tribes, including the following guarantees:

You will be allowed to pasture your animals on land not claimed or occupied by

settlers, white men. You will be allowed to go on the roads, to take your things to

market, your horses and cattle. You will be allowed to go to the usual fishing

places and fish in common with the whites, and to get roots and berries and to kill

game on land not occupied by the whites; all this outside the Reservation.

On 9 June 9 1855, the day that the treaty with the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla was

signed, Governor Stevens again assured the assembled tribes that the written treaties faithfully

reflected the oral explanations previously given to them at the council ground stating as follows:

My Friends, Today we are all I trust of one mind. Today we shall finish the

business which brought us together. Yesterday the Yakamas had not made up

their minds fully. Today they and ourselves agree; the papers have been drawn up.

A paper for the Nez Perces; they live on one Reservation. A paper for the

Walla Wallas, Cayuses, and Umatillas; they have their Reservation on the

Umatilla. And a paper for the Yakamas; they have their Reservation. These papers

engage us to do exactly what we have promised to do.

Again, Governor Stevens (1985), when addressing a reluctant Nez Perce chief, Looking Glass at

Walla Walla, stated as follows:

Looking Glass knows that in this [Nez Perce] reservation settlers cannot go, that

he can graze his cattle outside of the reservation on lands not claimed by settlers,

that he can catch fish at any of the fishing stations, that he can kill game and go to

buffalo when he pleases, that he can get roots and berries on any of the lands not

occupied by settlers.

Although slightly different wording was used in the treaties with the several tribes, it is doubtful

that this was intended to secure different off-reservation fishing rights to the different Indian

tribes. The right to use roads in order to exercise these and other rights essential to their

subsistence and system of trade and exchange also is affirmed repeatedly. For example, on 4

June, Governor Stevens states: "You will be near the Great Road and can take your horses and

your cattle down the river and to the Sound to market" (Slickpoo and Walker 1973:110).

Followed by another statement on 5 June describing their freedom of movement as follows:

"They [same as above] shall have the same liberties outside the Reservation to pasture animals

on land not occupied by whites, to kill game, to get berries and to go on the roads to market"

(Slickpoo and Walker 1973:114). Again on 5 June, he states: "My brother has stated that you

will be permitted to travel the roads outside the Reservation" (Slickpoo and Walker 1973:115).

Once again: "Now if our chief desires to construct such a road [railroad] through your country

we want you to agree that he shall have the privilege. You would have the benefit of it as well as

other people" (Slickpoo and Walker 1973:115). Finally Stevens says: "Now as we give you the

privilege of traveling over roads, we want the privilege of making and travelling roads through

your country, but whatever roads we make through your country will not be for your injury"

(Slickpoo and Walker 1973:116).

Most of the assurances communicated during the treaty negotiations in June of 1855 appear as

articles in the ratified treaties. For example, fishing and other off-reservation rights appear as part

of Article 3 in the Treaty with the Yakama (Kappler 1904):

The exclusive right of taking fish in all the streams, where running through or

bordering said reservation, is further secured to said confederated tribes and bands

of Indians, as also the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed places in

common with citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary buildings for

curing them; together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries,

and pasturing their horses and cattle upon open and unclaimed land.

In the Treaty with the Nez Perce (Kappler 1904), fishing and other off-reservation rights are

described as part of Article 3:

The exclusive right of taking fish in all the streams where running through or

bordering said reservation, is further secured to said Indians; as also the right of

taking fish at all usual and accustomed places in common with citizens of the

Territory; and of erecting temporary buildings for curing, together with the

privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses and

cattle upon open and unclaimed land.

Fishing and other off-reservation rights appear in Article 1 of the Treaty with the Walla Walla,

Cayuse, and Umatilla (Kappler 1904):

Provided also, that the exclusive right of taking fish in the streams running

through and bordering said reservation is hereby secured to said Indians, and at all

other usual and accustomed stations in common with citizens of the United States,

and of erecting suitable buildings for curing the same; the privilege of hunting,

gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their stock on unclaimed lands in

common with citizens, is also secured to them.

Similar language guaranteeing reserved rights to continue off-reservation subsistence pursuits

and travel are also found in the July 1855 Treaty Stevens negotiated with the Flathead, Pend

d'Oreille, and Kootenai.

In yet another Stevens treaty of 1855 (17 October) negotiated with the Blackfeet and various

tribes at the council ground on the upper Missouri River near the mouth of the Judith River in the

then Territory of Nebraska (now Montana), the reserved treaty rights of western tribes on the

upper Missouri and Yellowstone rivers are clearly recognized and affirmed including a right to

travel to and from the common hunting territory. Article 3 of this treaty describes the area and

rights reserved to the tribes as follows:

The Blackfoot Nation consent and agree that all that portion of the country

recognized and defined by the treaty of Laramie as Blackfoot territory, lying

within lines drawn from the Hell Gate or Medicine Rock passes in the main range

of the Rocky Mountains, in an easterly direction of the nearest source of the

Musselshell river, thence to the mouth of Twenty-five Yard Creek, thence up the

Yellowstone River to its northern source, and thence along the main range of the

Rocky Mountains, in a northerly direction, to the point of beginning, shall be a

common hunting-ground for 99 years, where all the nations, tribes and bands of

Indians, parties to this treaty, may enjoy equal and uninterrupted privileges of

hunting, fishing and gathering fruit, grazing animals, curing meat and dressing

robes. They further agree that they will not establish villages, or in any other way

exercise exclusive rights within ten miles of the northern line of the common

hunting-ground, and that the parties to this treaty may hunt on said northern

boundary line and within ten miles thereof.

Provided, That the western Indians, parties of this treaty, may hunt on the trail

leading down the Musselshell to the Yellowstone; the Muscle Shell River being

the boundary separating the Blackfoot from the Crow territory.

And provided, That no nation, band, or tribe of Indians, parties of this treaty, nor

any other Indians, shall be permitted to establish permanent settlements, or in any

other way exercise, during the period above mentioned, exclusive rights or

privileges within the limits of the above described hunting-ground.

And provided further, That the rights of the western Indians to a whole or a part

of the common hunting-ground, derived from occupancy and possession, shall not

be affected by this article, except so far as said rights may be determined by the

treaty of Laramie with the Blackfeet (Kappler 1904).

This treaty designates routes of travel across the Rocky Mountains, places prohibitions on

intertribal warfare (except in self-defense against certain groups), and limits and designates

hunting areas to be used by tribes when travelling to and from this "common hunting ground." It

is significant that the Flathead, the Upper Pend d'Oreille, and the Kootenay are mentioned in this

treaty, because they were all closely linked by trade, marriage, political, and other ties to the

Yakama, Umatilla, Cayuse, and other western tribes (Anastasio 1972).

Trade and Exchange in the Plateau

Intensive studies of traditional systems of trade and exchange in the Plateau have been

undertaken by Walker (1967), Brunton (1968), Anastasio (1972), Stern (1993), and Smith

(1964). Walker (1967) draws the following conclusions concerning trade and exchange within

the region (paraphrased):

1. Cross-utilization of resources among tribal groups in the aboriginal Plateau was the rule, not

the exception; such resources included game, fish, roots, berries, furs, skins, stone, and other

materials not distributed evenly throughout the area.

2. Chinook Jargon, the trade language of the Chinookan tribes employed by the Yakama,

continued to be important in intertribal trade and exchange until at least the end of the nineteenth

century. Although widely used, it was limited in its vocabulary to a few hundred words, and

suitable primarily for trade and exchange. Like other tribal languages, it was not anyone's

primary language.

3. Traditionally, the tribal groups of the region lacked fully developed and centralized tribal

organization in the political sense; such tribalization came later when treaties established

reservations, head chiefs, tribal police, etc. Instead, families, villages, and occasionally bands

may be said to have possessed stewardship over certain resources such as fishing sites. Rights to

membership in such groups were usually determined by birth and marriage. Cross-utilization of

resources between different families, villages, bands, or other groups was mediated primarily

through trading partnerships, kinship ties, and social relationships that knitted together the

peoples of the Plateau into a single economic system.

4. Annual as well as geographic variation in the quality and quantity of subsistence resources in

the Plateau was substantial in the aboriginal period. Subsistence activities thus required regular,

extensive travel throughout the Plateau and in the neighboring Plains, Great Basin, and

Northwest Coast. The Yakama joined with eastern groups such as the Nez Perce, Kootenay,

Pend d'Oreille, and Flathead to journey into the Plains to hunt bison, to trade, and to raid. This

exploitation of the bison in the Plains was similar to exploitation of the salmon and other

resources of the Columbia and its tributaries in the central and western Plateau. Southern Plateau

groups also exploited resources of the northern Great Basin in a similar manner.

5. By the time of contact with Euroamericans the Yakama had adopted the horse and been

influenced by Plains cultural patterns which greatly intensified and expanded the scope of their

system of trade and exchange. The impact of the fur trade accelerated the system even more.

In 1967, Walker (1967) cited Griswold (1954) and Daugherty and Fryxell (1962) who described

some of the prehistoric and traditional trading activity conducted through a network of trails

ultimately connecting the Plains through the Plateau to the Northwest Coast:

Not unexpectedly the materials traded along these routes were varied. The Plateau

tribes carried eastward coastal commodities such as the shells of dentalia, haliotis,

and olivella (all of which were used widely for ornamentation) and [other] Plateau

products such as salmon pemmican, salmon oil, woven bags, horn bows, wooden

bows, greenstone pipes, lodgepoles, wild hemp, berries, meats, moose skins,

spoons and bowls of mountain sheep horn, and basketry. In return, the Plains

tribes traded bison robes, father bonnets, catlinite pipes, obsidian, buffalo horn,

buffalo bone beads, paints, buckskin clothing, and horse equipment (Griswold

1954). Direct archaeological evidence, consisting of hundreds of Olivella shells

and obsidian fragments recovered from the Marmes Rockshelter site and other

sites in Yakama territory, demonstrate that similar exchange of materials had

begun at least 7000 years ago.

Walker (1967) continues as follows (paraphrased):

The Yakama were, with the Nez Perce and Flathead, a primary link between The

Dalles-Celilo region [and coast] and the Flathead [group]. Their importance in

introducing Plains influences to the Plateau is well known (Ray 1939). Plateau

groups employed a number of mechanisms to facilitate this trade. Important

among them were the annual trade fairs held in places like The Dalles-Celilo area,

the Yakima Valley, the junction of the Snake and Columbia rivers, the Upper

Columbia River and its tributaries, the Upper Missouri River, and the Upper

Snake River in southern Idaho. In 1814 Alexander Ross (Griswold 1954:115-116)

visited one such fair in the Yakima Valley which he described in the following

manner:

"We had scarcely advanced three miles when a camp of the true Mameluke style

presented itself; a camp of which we could see the beginning but not the end! It

could not have contained less than 3,000 men, exclusive of women and children,

and triple that number of horses. It was a grand and imposing sight in the

wilderness, covering more than six miles in every direction. Councils, root

gathering, hunting, horse-racing, foot-racing, gambling, singing, dancing,

drumming, yelling, and a thousand other things which I cannot mention were

going on around us."

Another major contributor to our understanding of Plateau trade and exchange is Anastasio

(1972). His 1955 dissertation on Plateau task groupings has been revised, updated, and published

through Northwest Anthropological Research Notes as "The Southern Plateau: An Ecological

Analysis of Intergroup Relations." In this important contribution he draws a number of

conclusions concerning the traditional patterns of Plateau trade and exchange. For example, he

(Anastasio 1972:175) describes the following customs that sustained this system of trade and

exchange:

Protection and hospitality, or at least tolerance, were extended even to members

of an enemy group who manifested friendly intentions or came on official

intergroup business and provided that there had not been a recent clash with that

enemy group in which loss of life had been sustained by the host group. ...

Visitors were expected to obey group norms and were not exempt if they

infringed on the rights of the host group.

Anastasio (1972:184) summarizes his lengthy analysis as follows:

To summarize, the many intergroup activities of the Plateau were possible

because of a series of mechanisms which allowed interaction for all sorts of tasks.

There were intergroup norms which limited the use of warfare as a mechanism of

intergroup relations and permitted the settlement of intergroup disputes by

discussion, arbitration, and agreement. There were norms permitting the coutilization of resource sites and the peaceful congregation of groups for

ceremonies, conferences, and games. There was group responsibility for the

welfare of person and property of visiting members of other groups. There were

norms for the exchange of goods and services and the extension of kinship and

friendship ties across groups. Such patterns of agreement and interaction can

hardly be seen as the result of fortuitous and haphazard contacts. They were

established, maintained, and ordered by consensus. Therefore, we would say that

the norms of intergroup relations and the relevant beliefs and values formed part

of an intergroup culture. The component groups were bound together by their

acceptance of this culture.

Theodore Stern in his recent Chiefs and Chief Traders (1993:18-33) describes the "Columbian

Trading Network," observing first that "despite their [mostly American traders] growing

importance [in the period before 1846], they cannot have been responsible for giving rise to the

network: they had only a traffic already in existence." Further, Stern (1993:26) says:

Exchange was deeply embedded in social relationships. Something of its complex

nature can be seen in the career of Kammach, son of a headman and himself in

time to become a headman of the Tualatin Kalapuya, dwelling above the falls of

the Willamette. Trade such as his brought to the Kalapuya exotic articles

including Klickitat baskets, woven mountain goat wool blankets from the Salish

of the western Plateau, and buffalo robes from the Plains. Kammach early aligned

himself with the interests of the prominent Clackamas Chinook leader, Cassino.

When he thereafter married the daughter of a Chinook headman&endash;either

Clackamas or Wishram-Wasco&endash;his father paid over a bride price of

twenty slaves and ten rifles. Annually thereafter, Kammach visited

friends&endash;in all likelihood trading partners&endash;among the Luckiamute

and Mary's River bands of Kalapuya in the middle valley, as well as the Alsea on

the coast, in trips that might last six months. He brought them horses and money

dentalia, together with rifles, blankets, coats, tobacco, and gunpowder. From them

he received in return slaves, beaver skins, buckskins, and other hides. These he

handed over to his father-in-law, perhaps as a supplement to the bride price, but

surely as something more: for his father-in-law was probably the source of his

trading goods, and in turn traded the beaver pelts and the hides at Fort Vancouver,

while trading the slaves within the native network.

Additionally Stern (1993:30-31) says:

In the interregional trade of the Northern Plains and Great Basin, formality and

control were greater, in part as an expression of Plains ceremonialism. Recalled

one man of Palus-Nez Perce ancestry, when the Plateau party arrived, "the Crow

chief would indicate to us the place where our people were to pitch their separate

camp circle. Each man had a trading partner who put by goods to trade" against

the time they came together. When Salishan parties encountered erstwhile foes on

the prairies, leaders of the two sides might smoke together, then announce a

trading truce for a set period. During that time, then, members of the two parties

danced, gambled, and traded together. Often, less than a day after the groups had

separated, members on either side might already be engaged in trying to cut off

stragglers or run off horses from the other group.

Finally he (Stern (1993:30-31, 33) says that:

Within the Plateau, it was not the coming of British and American traders alone

that gave fresh impetus to exchange. Speaking of the upper Columbia in terms

broadly applicable to the Plateau as a whole, Teit [1928] remarks that in those

days when trade was conducted either afoot or by canoe, the articles exchanged

had been of necessity light and of high value, while trading parties were small and

infrequent. All this was changed with the advent of the horse: in those latter days,

both the volume and variety of goods carried increased, being extended to include

raw and semi-processed materials. Routes became more direct and led overland,

while parties grew in size and trading ventures in frequency.

Thus in a manner largely unacknowledged by Euroamerican traders, they

operated alongside, and sometimes in competition with, a native trading network,

whose participants brought native expectations into their dealings with these

foreign newcomers. It is not enough, however, to compare their systems as

distinct entities: further features lie in the interaction of tribe with tribe in

juxtaposition with the interaction of tribe and traders. It is to the peoples of the

Nez Percés District that we next turn. The three chapters that follow provide a

summary overview of those peoples and their cultures, and of their leaders.

Focusing on more recent times in the 1960s, Brunton (1968:1-28) has discovered that the Nez

Percés and Colvile districts of the Hudson's Bay Company era continue to function as multi-

tribal ceremonial groupings, divided roughly along Salishan and Sahaptian language boundaries

(significant political alliances within these ceremonial groupings have been detected by Walker).

This organization of Plateau social and cultural groupings, and their relationship to other

ceremonial groupings in the Northwest Coast, Great Basin, and Northwestern Plains conforms to

the views cited above of Walker, Anastasio, and Stern. While Brunton (1968:21-22) fails to

pursue the economic and political functions of these groupings, that should not prevent us from

understanding that these structures continue to serve kinship, economic, and political functions at

this time despite the imposition of the reservation system.

Yakama Trade and Exchange

In 1854 Gibbs, ethnographer for Governor Stevens, noted the intensity and wide geographical

extent of Yakama trade and exchange, particularly evident among the Klikitat. Gibbs (1854:403)

described them as follows:

The Klikatats and Yakimas, in all essential peculiarities of character, are identical,

and their intercourse is constant; but the former, though a mountain tribe, are

much more unsettled in their habits than their brethren.... They manifest a peculiar

aptitude for trading, and have become to the neighboring tribes what the Yankees

were to the once Western States, the travelling retailers of notions; purchasing

from the whites feathers, beads, cloth, and other articles prized by Indians, and

exchanging them for horses, which in turn they sell in the settlements.

The extent of Yakama involvement in interregional trade and exchange with Northwest Coast

groups has also been investigated by Allan Smith (1964) in his study of tribal uses of Rainier

National Park. He notes that traditional Yakama trails (passes) through the Cascades included

Naches, Chinook, Carlton, Cowlitz, and White passes which range from 4100 to 5440 ft. of

elevation. His informants also affirm that the passes used by whites today were those followed

by the Yakama. Smith (1964) provides a list of passes known to the Yakama which are presented

in Table 1.

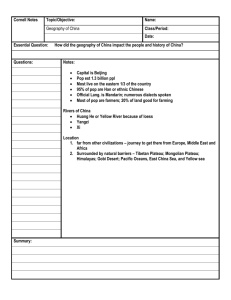

TABLE 1. PASSES IN YAKAMA COUNTRY (after Smith 1964)

Pass ca. Elev. Location

Snoqualmie 3000 Between Coal Cr. (Yakima R. system) & S. Fork Snoqualmie R.

Yakima 3525 Between Roaring Creek and Cedar River

Meadow 3650 Between Meadow Creek and Sunday Creek (Green River system)

Dandy 3750 Between Meadow Creek and Sunday Creek (Green River system)

Stampede 3800 Stampede Creek and Sunday Creek (Green River system)

Sheeta 3450 Cabin Creek and Green River

Tacoma 3450 Cabin Creek and Green River

Green 4988 Middle Fork Naches River & Greenwater River (White R. system)

Chinook 5440 Rainier Fork American River & Chinook Creek (Cowlitz system)

Carlton 4100 Bumping River and Carlton Creek (Cowlitz system)

Cowlitz 5191 Indian Creek and Summit Creek (Cowlitz system)

White 4500 Clear Creek and Milridge Creek (Cowlitz system)

Tieton 5050 North Fork Tieton River and Clear Fork Cowlitz River

Chinook Pass (5440 feet)

According to Smith, this pass linked the Rainier Fork of the American River on the east with the

low divide in the Park separating the headwaters of the White River on the north from those of

the Chanapscosh on the south. Specific information confirms use of this pass and is provided by

the Yakama. Information indicates that their forebears used to travel through Chinook as well as

Naches passes. According to the late Alec Saluskin, who visited the Rainier berry fields once

when he was a youth, the trails used by the members of the Yakama follow the present trails

through these two passes almost exactly.

Naches Pass (4988 feet)

Smith states that Naches Pass lay just to the northeast of the northwestern corner of Rainier Park,

and hence north along the Cascade Divide from Chinook Pass. According to his informants, the

Yakama were familiar with and used this pass. The trail through this defile was said to have

followed the present trail. Smith states that this defile was also known to Puget Sound tribes and

used by them. For example, members of the Nisqually tribe are reported to have often traveled

east of the Mountains through Naches Pass and Cowlitz Pass. The route by way of Naches Pass

between the coast and the Plateau ran slightly to the north of Mt. Rainier Park. Information from

a Muckleshoot informant, Louis Starr, indicates that practically all Muckleshoot could speak

Yakama but not the reverse. He said that the Muckleshoot went to the Yakama country to get

things they could not obtain in their own territory, such as certain roots. Similarly, the Yakama

came over to the Muckleshoot country to catch and dry fish. The Muckleshoot trail, he reported,

went along the White River, Greenwater River, and then over Naches Pass.

Carlton Pass (4100 feet)

According to available maps and to Yakama informants, Smith says that this pass is the first

significant break in the crests of the Cascades south of Chinook Pass. It lies about 1 mile

southeast of the point where the eastern boundary of Mt. Rainier National Park leaves the

Cascades Divide and breaks away to the southwest. According to the Mt. Aix U. S. G. S.

Quadrangle, a trail today ascends the Bumping River from the east, moves through this pass, and

descends Carlton Creek in a southwesterly direction to Summit Creek and this stream to the

Ohanapecosh. In this valley it unites with the Nisqually River-to-Cowlitz Pass trail. It thus

provides another link between the country of the Yakama and Taidnapam territory.

Cowlitz Pass (5191 feet)

This pass, also termed Packwood Pass by Smith, lies about 6 miles southeast along the Divide

from the southeastern corner of Rainier Park. Although no data were obtained from informants

demonstrating aboriginal travel through this pass, the literature shows this to have been the case.

For example, the Nisqually are reported by Haeberlin and Gunther (1930) to have often traveled

east of the Mountains using Cowlitz Pass. The Yakama evidently knew of Cowlitz Pass and used

it. Just east of the Muckleshoot and the Nisqually lived the Klikitat, whose lands extended south

to the Columbia River and eastward to the mountains. The Klikitat in family groups crossed the

mountains once a year in July or August, using Cowlitz Pass. There is a stream near the

waterworks in Tacoma which the Klikitat used to travel down to the Sound. "Klikitat" was

sometimes used for all Sahaptin-speaking peoples immediately to the east of the Cascades.

Passes North of Naches Pass: Yakima and Snoqualmie

According to Smith, several of these more northerly passes through the Cascades were used as

thoroughfares between the Plateau and the Coast. Smith relies on Teit (1928) in concluding that

the Wenatchi occupied at least a part of the recent Yakama territory in earlier days. Tradingparties of Wenatchi went toward the coast by way of the Yakima, Snoqualmie, and other passes

through the Cascades, where they traded with Snoqualmie. The Wenatchi also used other passes

through the Cascades, where they traded with Snoqualmie, Snohomish, Nisqually, Puyallup, and

Cowlitz. The first horse seen by the Coast tribes was brought over by Wenatchi. Both of the

passes mentioned specifically are located to the northeast of Mt. Rainier, near the headwaters of

the Yakima River in the vicinity of Keechelus Lake. Smith also notes that Teit (1928) described

large, well-armed and well-equipped parties of Wenatchi annually passing through the Yakama

country to The Dalles. Smith believes that this indicates that the Wenatchi, on their trading

expeditions to the west of the Cascades, probably also followed routes through some Cascades

passes south of Yakima Pass.

Passes South of Cowlitz Pass: White and Tieton

Immediately south of Cowlitz Pass were White and Tieton passes. Smith notes that as with

Carlton and Cowlitz to the north, these two joined the country of the Yakama with Taidnapam

territory. The Taidnapam to the west of this pass and the Yakama to the east were not only

Sahaptin-speakers but were also culturally close, being linked by frequent intermarriage.

Cayuse Pass (4700 feet)

Evidently one trail led north and south near Mt. Rainier. This was the one between the

headquarters of the White River system on the north and the source streams of the CowlitzChanapecosh system on the south. The pass through which travelers passed from one of these to

the other was Cayuse Pass.

According to Smith (1964:149-226), the reasons impelling the Yakama to engage in transCascade travel were various. The natural products&endash;particularly foods&endash;of the

coastal slopes and the more eastern hills were in some respects sharply different, and, being so,

often desirable to those of the contrasting ecosystem. Dried eastern roots were carried westward

over the Cascades Divide through the mountain passes as dried coastal products found their way

eastward to the Yakama.

Smith claims that movement for the sake of trade occurred in both directions across the

Cascades. Plateau groups journeyed westward to the Puget Sound tribes for this purpose and

parties of the latter crossed the mountains in an easterly direction to trade with Plateau peoples.

The evidence suggests, however, that Plateau groups were probably more commonly the active

members in this commercial arrangement, themselves undertaking the mountain crossing.

Smith (1964:244) cites Haeberlin and Gunther (1930:32) concerning Nisqually trade with the

Yakama as follows:

The Nisqually traded largely with the Klikitat [a name used for most member

groups of the Yakama], using shell money for payment. Shell money was highly

prized by the Indians east of the mountains and the coast tribes used it more in

trading with them than among themselves. The shell money which the Klikitat

obtained from the Nisqually they in turn passed on to the Indians of Idaho and

Montana. When the Klikitat came to the coast in summer they bought clams,

herring, smelts and berries. In return they gave the Nisqually dried Columbia

salmon, which is highly prized by the coast people. They also brought dressed

buckskins and clothing made of skins. The Nisqually never bought baskets from

the Klikitat because they made better ones themselves, but the Klikitat bought

coiled baskets from the Nisqually.

According to Smith (1964:246), Teit (1928) reports that the Wenatchi also journeyed to the west

of the Cascades to trade with Nisqually, Puyallup, and Cowlitz. Teit continues:

A great impetus was given to trading with the introduction of the horse.

Rootcakes, dried berries, buffalo robes, and many other heavy or bulky packs,

which in former days it did not pay to carry, were not transported across the

mountains. Before the introduction of the horse, the trading with Coast tribes was

chiefly in light and valuable articles. Pipes, tobacco, ornaments of certain kinds,

Indian hemp, dressed skins, bows, and some other things, were sold to the Coast

tribes, the chief articles received in return being shells of various kinds. Some

horses were also sold to the Coast people.

In his summary description of reasons for this trans-Cascades travel Smith claims that the

Yakama followed these trans-Cascades trails to secure supplies of various natural resources

available in the region of Rainier Park as well as to enter the country of their friendly Northwest

Coast neighbors and share their food resources. For example, they fished for red salmon in the

Cowlitz River in Taidnapam country. According to one of Smith's Muckleshoot informants, the

Yakama also journeyed westward through Naches Pass into Muckleshoot territory to catch and

dry fish. On occasion, coastal groups passed east of the Cascades to secure local foods. For

example, the Muckleshoot traveled through Naches Pass to Yakama country to obtain things they

could not obtain in their own territory, including certain roots, berries, and other products.

There was also some movement along the trails over the Cascade Divide to obtain spouses and

then subsequently to maintain contact with relatives. Material items moved east and west through

the passes as part of this social interaction. Especially close relationships were maintained

between the Taidnapam and Yakama. Moreover, both Nisqually-Puyallup and Muckleshoot

informants reported to Smith substantial numbers of Yakama intermarriages in the upriver

villages of their respective tribes. This intermarriage was often the result of Coast men securing

Yakama wives and establishing virilocal residences. The same was the case, of course, to an

even greater extent with the Taidnapam. Some few Nisqually-Puyallup and Muckleshoot women

were also married to Yakama men and maintained their homes with their husbands' group

according to Smith. In a similar vein, Haeberlin and Gunther (1930:11) note: "Many Nisqually

spoke Klikitat and there were frequent intermarriages between the two tribes." These authors

evidently employ "Klikitat" as a general designation for all Sahaptins on the eastern side of the

Cascades, thus it is likely that at least some Yakama were involved. According to Smith, it is

also clear that goods and other material possessions brought through the passes were wagered in

intertribal stick (bone) games (Brunton 1968). Gambling was either a secondary aim to the travel

or developed, after the groups had met, as a pastime of mutual interest. Finally, the passes and

trails through the Cascades were used by war parties, despite the peaceful relations that normally

prevailed between the Coastal and Plateau tribes of this area (Teit 1928:123).

Conclusions

The Yakama were part of a prehistoric, protohistoric, and historic system of trade and exchange

that linked them with other Plateau tribes as well as more distant tribes of the Northwest Coast,

Plains, and Great Basin culture areas. The Yakama system of trade and exchange was essential

for maintenance of the Yakama way of life. Through it they obtained fish and other aquatic

resources, large and small game, slaves, decorative objects, buffalo products, coastal products,

desert products, and other items essential to their survival. The Yakama exercised free and open

access to trade centers and trade networks in order to maintain their system of trade and

exchange.

The Hudson's Bay Company trading operation in the Columbia Basin was built on and operated

within the traditional tribal system of trade and exchange. Rather than replacing it, the Hudson's

Bay Company system intensified this traditional system. The Yakima Treaty of 1855 contains

assurances that the Yakama and other treaty tribes would be free to continue their free and open

use of roads and trails to reach their customary trade centers, fisheries, hunting grounds, and

other areas they accessed as part of their traditional system of trade and exchange.

Following the Treaty negotiation and ratification, the Yakama continued to exercise offreservation travel for Treaty purposes and continue to do so now as is reflected in their numerous

off-reservation fisheries, root and berry gathering grounds, and hunting areas.

References Cited

Ames, Kenneth M. and Alan G. Marshall 1981 Villages, Demography and Subsistence

Intensification on the Southern Columbia Plateau. North American Archaeologist, 2(1):25-52.

Anastasio, Angelo 1972 The Southern Plateau: An Ecological Analysis of Intergroup Relations.

Northwest Anthropological Research Notes, 6(2):109-229.

Aoki, Haruo and Deward E. Walker, Jr. 1989 Nez Perce Oral Narratives. University of

California Publications in Linguistics, Vol. 104. Berkeley.

Beavert, Virginia and Deward E. Walker, Jr. 1974 The Way It Was: Anaku lwacha, Yakima

Indian Legends. Yakima: Consortium of Johnson O'Malley Committees of Region IV, State of

Washington, Franklin Press.

Boyd, Robert T. 1985 The Introduction of Infectious Diseases Among the Indians of the Pacific

Northwest, 1774-1874. Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle. Ann Arbor:

University Microfilms International.

Brunton, Bill B. 1968 Ceremonial Integration in the Plateau of Northwestern North America.

Northwest Anthropological Research Notes, 2(1):1-28.

Chance, David H. 1973 Influences of the Hudson’s Bay Company on the Native Cultures of the

Colvile District. Northwest Anthropological Research Notes, Memoir No. 2. Moscow.

Cook, S. F. 1955 The Epidemic of 1830-33 in California and Oregon. University of California

Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 43(3):303-326. Berkeley.

Cressman, L. S. in collaboration with David L. Cole, Wilbur A. Davis, Thomas M. Newman, and

Daniel J. Scheans 1960 Cultural Sequences at The Dalles, Oregon: A Contribution to Pacific

Northwest History. American Philosophical Society Transactions, 50:10. Philadelphia.

Daugherty, Richard D. 1973 The Yakima People. Phoenix: Indian Tribal Series.

Drury, Clifford M. 1958 The Diaries and Letters of Henry R. Spalding and Asa Bowen Smith

Relating to the Nez Perce Mission, 1838-1842. Glendale: Arthur R. Clark

Elmendorf, William W. 1965 Linguistic and Geographic Relations in the Northern Plateau Area.

Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 21(1):63-77.

Erickson, Kevin 1990 Marine Shell Utilization in the Plateau Culture Area. Northwest

Anthropological Research Notes, 24(1):91-144.

Fryxell, Roald and Richard D. Daugherty 1962 Interim Report: Archaeological Salvage in the

Lower Monumental Reservoir, Washington. Washington State University, Laboratory of

Anthropology, Report of Investigations, No. 21. Pullman.

Gibbs, George 1854 Report of Mr. George Gibbs to Captain Mc'Clellan, on the Indian Tribes of

the Territory of Washington. In Report of Explorations and Surveys to Ascertain the Most

Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific

Ocean, 1:402-434. 33rd Congress, 2nd Session, Senate Executive Documents, Vol. 12, No. 78

(Serial Set No. 758); and House Executive Documents, Vol. 11, Part 1, No. 91 (Serial Set No.

791). Washington. Reprinted 1978 as Indian Tribes of Washington Territory by Ye Galleon

Press, Fairfield.

Griswold, Gillett G. 1954 Aboriginal Patterns of Trade Between the Columbia Basin and The

Plains. Master's thesis, Montana State University [University of Montana]. Missoula.

Haeberlin, Hermann K. and Erna Gunther 1930 The Indians of Puget Sound. University of

Washington Publications in Anthropology, 4:1.

Haines, Francis D., Jr. 1937 The Nez Perce Delegation to St. Louis in 1831. Oregon Historical

Quarterly, 37(4):329-333.

Kappler, Charles J. 1904 Indian Affairs, Laws and Treaties, 2nd edition. 58th Congress, 2nd

Session, Senate Executive Documents, Vol. 39, No. 319 (Serial Set Nos. 4623, 4624).

Washington.

Kirk, Ruth F. and Richard D. Daugherty 1978 Exploring Washington Archaeology. Seattle:

University of Washington Press.

Leonhardy, Frank C. and David G. Rice 1970 A Proposed Culture Typology for the Lower

Snake River Region, Southeastern Washington. Northwest Anthropological Research Notes

4(1):1-29.

McClellan, George B. 1855 General Reports of the Survey of the Cascades, Feb. 25, 1853. 33d

Congress. 2d Session. House Executive Document, No. 91, pp. 188-201 (Serial Set No. 791).

Washington.

Meinig, D. W. 1968 The Great Columbia Plain. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Nelson, Charles M. 1969 The Sunset Creek Site (45-KT-28) and its Place in Plateau Prehistory.

Washington State University, Laboratory of Anthropology, Report of Investigations, No. 47.

Pullman.

Osborne, Douglas 1955 Nez Perce Horse Castration&endash;A Problem in Diffusion. Davidson

Journal of Anthropology, 1(2):113-122. Reprinted 1987, Northwest Anthropological Research

Notes, 21(1/2):121-130.

Perkins, Henry K. W. 1843 History of the Oregon Mission. The Christian Advocate and Journal,

13 September.

Ray, Verne F. 1939 Cultural Relations in the Plateau of Northwestern America. Publications of

the Frederick Hodge Anniversary Publication Fund, Vol. 3. Los Angeles.

Relander, Click 1962 Strangers on the Land. Yakima: Franklin Press.

Schuster, Helen H. 1975 Yakima Indian Traditionalism: A Study in Continuity and Change.

Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms

International.

Simpson, George 1931 Fur Trade and Empire: George Simpson's Journal, Frederic Merk,

editor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Slickpoo, Allen P., Sr. and Deward E. Walker, Jr. 1973 Noon Nee-Me-Poo (We, the Nez Perces):

Culture and History of The Nez Perces. Lapwai: Nez Perce Tribe.

Smith, Allan H. 1964 Ethnographic Guide to the Archaeology of Mt Rainier National Park.

Report to National Park Service, Seattle from Washington State University, Pullman.

Stern, Theodore 1993 Chiefs and Chief Traders. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press.

Stevens, Isaac I. 1985 A True Copy of the Record of the Official Proceedings at the Council in

Walla Walla Valley, 1855. Fairfield: Ye Galleon Press.

Strong, William 1961 Kinckerbocker Views of the Oregon Country: Judge William Strong's

Narrative (1878). Oregon Historical Quarterly 62(1):57-87.

Teit, James A. 1928 The Middle Columbia Salish. University of Washington Publications in

Anthropology, 2(4):83-128. Seattle.

Thwaites, Reuben Gold, editor 1904-05 Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition,

1804-1806. New York: Dodd, Mead, & Co. Reprinted 1959, Antiquarian Press, New York.

Reprinted 1969, Arno Press, New York.

Walker, Deward E., Jr. 1967 Mutual Cross-Utilization of Economic Resources in the Plateau: An

Example from Aboriginal Nez Perce Fishing Practices. Washington State University, Laboratory

of Anthropology, Report of Investigations, No. 41. Pullman.

_____.1968 Conflict and Schism in Nez Perce Acculturation; a Study of Religion and Politics.

Pullman: Washington State University Press. Reprinted 1985 by University of Idaho Press,

Moscow.

_____.1969 New Light on the Prophet Dance Controversy. Ethnohistory, 16(3):245-255.

_____.1972 Measures of Nez Perce Outbreeding and the Analysis of Cultural Change. In The

Emergent Native Americans, Deward E. Walker, Jr., editor, pp. . Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

Warren, Claude N. 1968 The View from Wenas: A Study in Plateau Prehistory. Occasional

Papers of the Idaho State University Museum, No. 24. Pocatello.

Warren, Claude N., Allan L. Bryan, and Donald R. Tuohy 1963 The Goldendale Site and Its

Place in Plateau Prehistory. Tebiwa 6(1):1-20.

Zucker, Jeff, Kay Hummel, and Bob Hogfoss. 1983 Oregon Indians: Culture, History, and

Current Affairs: An Atlas and Introduction. Portland: Oregon Historical Society.

Return to TOC