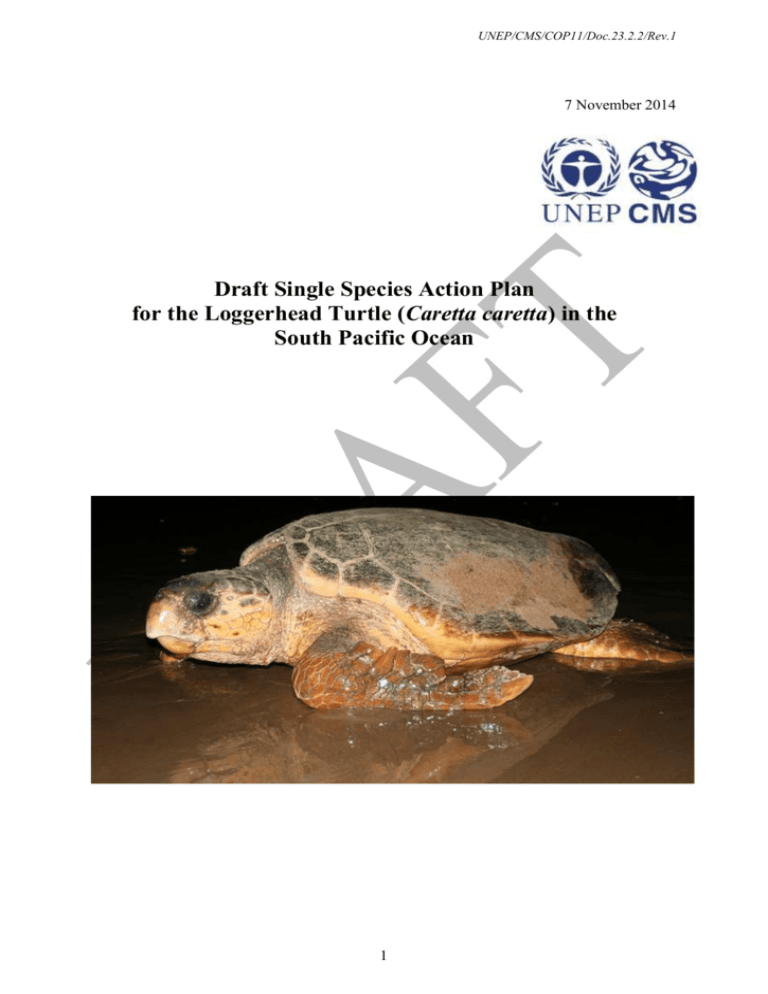

Draft Single Species Action Plan for the Loggerhead Turtle

advertisement