Word, 597.5 ko

advertisement

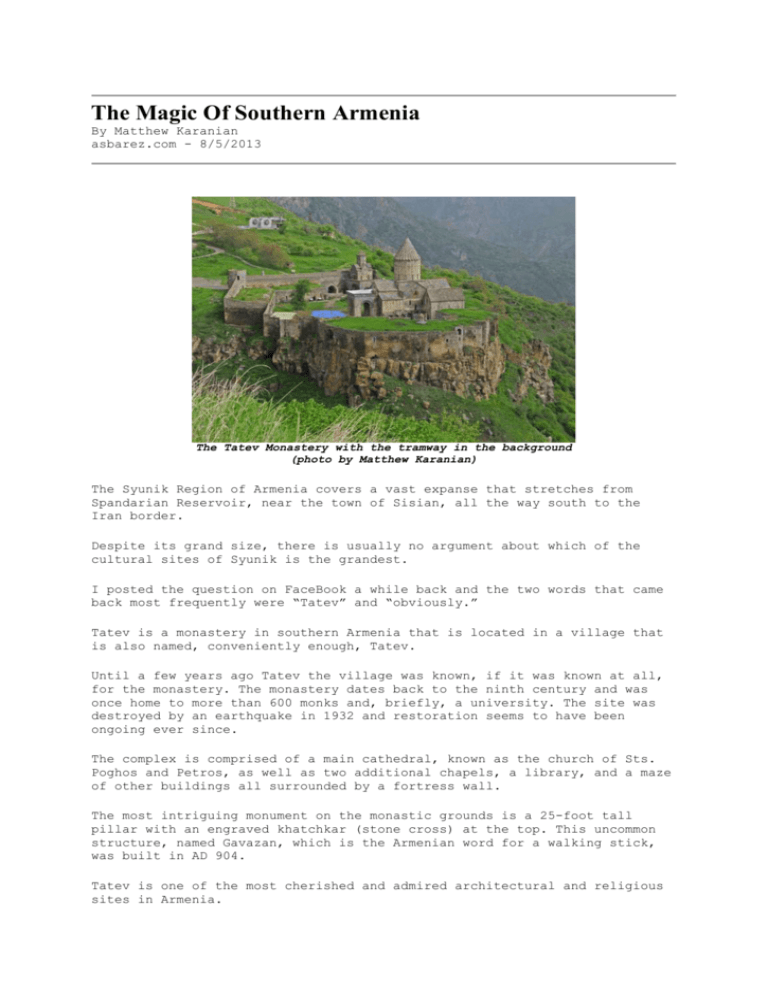

The Magic Of Southern Armenia By Matthew Karanian asbarez.com - 8/5/2013 The Tatev Monastery with the tramway in the background (photo by Matthew Karanian) The Syunik Region of Armenia covers a vast expanse that stretches from Spandarian Reservoir, near the town of Sisian, all the way south to the Iran border. Despite its grand size, there is usually no argument about which of the cultural sites of Syunik is the grandest. I posted the question on FaceBook a while back and the two words that came back most frequently were “Tatev” and “obviously.” Tatev is a monastery in southern Armenia that is located in a village that is also named, conveniently enough, Tatev. Until a few years ago Tatev the village was known, if it was known at all, for the monastery. The monastery dates back to the ninth century and was once home to more than 600 monks and, briefly, a university. The site was destroyed by an earthquake in 1932 and restoration seems to have been ongoing ever since. The complex is comprised of a main cathedral, known as the church of Sts. Poghos and Petros, as well as two additional chapels, a library, and a maze of other buildings all surrounded by a fortress wall. The most intriguing monument on the monastic grounds is a 25-foot tall pillar with an engraved khatchkar (stone cross) at the top. This uncommon structure, named Gavazan, which is the Armenian word for a walking stick, was built in AD 904. Tatev is one of the most cherished and admired architectural and religious sites in Armenia. But enough about the monastery. Today you’re apt to hear just as much about a new aerial tramway that links this monastery to the main road. The tram was built in 2010, some 1,100 years after the construction of the monastery. The tram’s 3.5 mile span has earned it an entry in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s longest. It’s called the Wings of Tatev, which is both descriptive, and also an allegorical reference to the origin of the name for the monastery. According to legend, when the main church of the monastery was under construction in AD 895 (give or take) a laborer slipped and fell into the gorge. While falling, the man pleaded, without avail, for God to grant him wings so that he could avoid death. He did this using the Armenian words “ta tev.” Whether the legend is true is anybody’s guess. My guess is that it’s not. But there’s no mistaking that Tatev is situated in a remote location, atop a steep gorge. Geographic isolation is the norm for monasteries in Armenia. The isolated location of Tatev and of many other religious sites may have helped to keep the monks focused on their work, free from worldly distractions. The remote siting also allowed these monasteries to be defended from marauding invaders, of whom Armenia has seen its share over the ages. In the modern era, however, this geographic isolation serves mostly as a deterrent to tourists who are contemplating how they can reach a site, and still get back home, or to their hotel, in one day. The aerial tramway at Tatev removes this deterrent. Passengers avoid the rugged road completely. Visitors are instead whisked from main highway to the monastery in 11 minutes. This is just one-quarter the time it would take to maneuver the hairpin turns of the roadway below—assuming that you are in a Jeep and that the road isn’t blocked by rockfalls, or washed out, or covered with snow and ice. And it’s a good two hours faster than the length of time it took me to reach Tatev on my first trek there, in 1995, when the so-called road was really just an improved trail. The rocks at Goris (photo by Matthew Karanian) There’s still a deterrent to reaching Tatev, of course. You have to be willing to ride high in the clouds above a mountain gorge in a small booth that’s suspended only by cables. Long cables. Three-and-a-half mile long cables. Some of us might just opt for the treacherous drive. No matter how you get to Tatev, there’s no denying that the aerial tram has stirred interest in the site. The President of Armenia even made a visit on the tram’s opening day, and was its first passenger. Tatev is the southernmost destination in Armenia for just about every tourist. Adventurists, however, think nothing of traveling farther south to Shikahogh Reserve. The one hundred square-kilometer Shikahogh Reserve is the only nature reservation in Armenia with primeval forests. Casual hikers can easily reach a grove of 2,000 year-old plane trees with trunk diameters that exceed four meters. This natural treasure is as esteemed in Armenia, perhaps, as is Redwood National Park in California. If you want to hike through the reservation you’ll need a permit, which you can easily get free of charge from the reservation’s director, at his office in the village of Shikahogh. When I obtained my hiking pemit recently, I also hired a guide to show me around. Even without a guide, and without a permit, there’s plenty of nature to see in the public areas near the villages of Shikahogh, Nerkin Hand, and Tsav. If you’re traveling to Shikahogh, just go and don’t sweat the details. The villages here are tiny (Nerkin Hand’s population is just 113), and everyone knows their neighbor, as well as how to get into the Reservation. If you can pronounce Shikahogh, chances are good that you’ll get pointed in the direction of the director’s cabin. From Shikahogh, there’s really no reason not to continue your journey to Meghri, the Armenian outpost that sits along the Armenia-Iran border. Well, actually, there are probably a handful of reasons not to continue. Lodging options in Meghri are rudimentary. There’s a lot of driving. And the climate tends to veer off in the directions of hot and hotter. But there’s no reason not to continue if you are an explorer. And if you’re already hiking among ancient plane trees in the forests of Shikahogh, then yes, you are an explorer. Meghri, population 4,775, is the final Armenian town before reaching Iran. The climate here is subtropical, and it is common to see pomegranates and figs growing on trees along the roads. The greatest historical site is a fortress that dates back to the tenth century. The fort is famous for its role in the successful defense of Meghri from a Turkish invasion in the eighteenth century. The defense was led by the Armenian leader Davit Bek. There’s also a trio of historic churches in town which date from the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries, and which are destinations for some Armenia pilgrims. For me, however, the greatest thrill of Meghri was standing near the bank of the Araks River, watching the steady flow of trucks crossing the open frontier with Iran, and contemplating how Iran—a fundamentalist Islamic Republic—has for so long enjoyed such a strong bond of friendship with Armenia—the world’s oldest Christian nation. I got the sense that the world is less black-and-white than I might have imagined. Logistics TATEV: The turnoff to Tatev is located 280 km south of Yerevan, just north of Goris, along the west side of the road. The tram operates daily except Monday, from 9 am to 6 pm. Roundtrip fare for tourists is 3,000 drams (about $7.50). Envy the residents of Tatev and of the surrounding towns who are allowed to ride free. SHIKAHOGH: Get a permit from the director of the reserve, in the village of Shikahogh. Hire a guide (optional) or hike independently. MEGHRI: Travel time from Goris, in good weather, is about four hours. Avoid traveling between Shikahogh and Meghri after dark, because of unpredictable road conditions. http://asbarez.com/109892/the-magic-of-southern-armenia/