Linguistic confusion in Captain Corelli`s Mandolin

advertisement

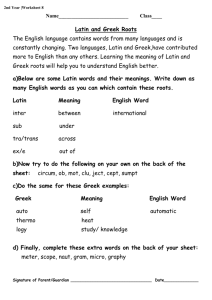

Linguistic confusion in Captain Corelli’s Mandolin Introduction A subtle theme brought to light by de Bernières in Captain Corelli’s Mandolin is that of linguistic confusion. The signs are everywhere, though to the casual reader they are not so much a theme as details in the plot. The Greek resistance graffiti on the walls, ingenuously misunderstood by the Italian soldiers. The dual and confused background of Drosoula, who sometimes dreams in Greek and other times in Turkish. The unwitting way in which Captain Corelli speaks profanities at local Greeks, including a priest, a little girl, and a dog. The comical but poignant relationship between the British parachutist Bunny Warren and the Greek shepherd Aenos, who takes Bunny’s English to be angel-speech. The subsequent life of Bunny on the island, where he is understood by no one, taken to be mad, and finally tags along with Father Arsenios – who also doesn’t understand him. The wonder of the British Special Forces when at Inousia they find “an island where every single person spoke fluent English, and where everyone was called either Lemmos or Pateras”, and when on Samos they discover “that for some inexplicable reason all the local doctors spoke French”. The list goes on. Of course, all of these things are related to the essential potpourri nature of Cephallonia. Over the centuries, wave after wave of invasion have created an enormous mixture of languages and cultures on the island. The six hundred-year Italian occupation with a twenty-year Turkish interlude, the Napoleonic presence, and the heavy British influence were all contributions to this. Of course, the most significant is that of the Italians, who caused a linguistic, behavioural and social fusion with the Greek tongue and Greek customs. So true is this that Cephallonia is seen as different even within Greece. The following passage from Dr Iannis’ history demonstrates this point. “The reader will readily see that to all intents and purposes the island was Italian for about six hundred years, and this explains a great many things that may puzzle the foreigner. The dialect of the island is replete with Italian words and manners of speech, the educated and the aristocratic speak Italian as a second language, and the campaniles of the churches are built into the structure, quite unlike the usual Greek arrangement whereby the bell is within a separate and simpler construction near the gates. The architecture of the island is, in fact, almost entirely Italian … and we lost the habit of wearing traditional dress long before this occurred in the rest of Greece. The Italians left us a European rather than an eastern outlook on life, our women were considerably freer than elsewhere in Greece … they were undoubtedly, along with the British, the most significant force that shaped our history and culture…” Nevertheless, there is an obvious and enormous gap between the two tongues, highlighted by the Italian misunderstanding of the graffiti. The occupying soldiers “mistook Rs for Ps, did not know that Gs can look like Ys or inverted Ls, … construed theta as a kind of O, … were baffled by the three horizontal strokes that could also be written as a squiggle … especially as the quirks of an individual’s handwriting could render the letters even more completely inscrutable.” This last remark demonstrates the personal nature of linguistic confusion. The origin may be at a national and cultural level, but it basically boils down to a frustrating void in communication between two people that can’t make a connection, who in the process of not understanding each other’s words do not understand each other. The dividing abyss that results needs no explanation. We need only examine our own reactions when we are confronted by the sound and tone of one speaking in a foreign language. It seems to be of another world so remote and baffling that we could call it, as Aenos so eloquently does, angel-speech. But returning to the general, we should ask: why does this difference between Italian and Greek – or any language for that matter – exist? The answer is infinitely complex, but it can be naïvely summarized as the separate evolution of languages. Those are lofty and vague words, true, but one would require a linguistic scholar’s knowledge to formulate an answer to the unanswerable question ‘why are we different?’ The bottom line is that sounds are different, meaning is the same; words and symbols are alien, feelings are universal; history and geography divided our tongues, and as yet nothing can satisfactorily unite them. However, languages do influence each other throughout the course of time. Greek (especially Ancient) and English are an example of this. Not just sayings like ‘It’s Greek to me’, but true affecting factors that change the language. The statistics are surprising. Approximately one third of the words in the English language (and other European languages) find their direct roots in the Greek language. It constitutes one of the richest foreign sources of the current English word stock. The total word stock of the English language is of roughly 170,000 words, of which over 40,000 are Greek. The basic concepts of thought and expression rest on Greek roots, which explains why Western European languages resort to the Greek glossary to express feelings, concepts, ideas, or to name objects and processes (consider analysis, dogma, philosophy, diagnosis, energy, epic, nostalgia). Latin, for all its merits and flexibilities, has difficulties in the production of compound words, which is where we usually have to make up new words to describe the encounter of two ideas or emotions in one. Which brings us to the English language itself. Its history shows us the true meaning of linguistic convergence, linguistic innovation, linguistic confusion and contribution. Anyone who questions its merits as our current lingua franca is clearly not informed about its historical development with the help of other languages and their many varied advantages. Out of the chaos blooms a form of clear communication, though there may be more misunderstandings than in German or Greek itself. Obviously it has its flaws, but they are acceptable given the circumstances. Old English (500-1100) Middle English (1100-1500) - Three major dialects appeared due to the west Germanic invasion on the British Isles, which brought along with it the language of northeastern region of the Netherlands: Northumbrian Mercian West Saxan - There was a little influence from Latin due to the conversion of Britain to Christianity in the seventh century. - Celtic-speaking inhabitants were therefore pushed out of England. - English was also influenced by the Vikings and by North Germanic words brought by Norse invasions. Early modern English (1500-1800) - Many classical Latin and Greek words were added into the English language during the Renaissance period. - Shakespeare highly influenced English with about 2000 innovated words and phrases. - The great Vowel shift caused great changes in pronunciation around 1400. - The printing press England in 1476 by William Caxton, which helped to reduce literacy, as books were more affordable. There were grammar and spelling rules set on the language and the first English dictionary was published in 1604. Late modern English (1800-2000) - Vocabulary has increased as the need to express new ideas that appeared during the Industrial Revolution and the rise of the technical society. - The industrial and scientific revolutions created a need for new words, for this the English relied heavily on Latin and Greek. (Oxygen,protein,nuclear, etc.) Today these innovations are most visible in computers and electronics.(byte, cyber). - Finally, the 20th century saw two world wars and the military influence on the language. The military slang entered the language like never before. So what does all of this pertaining to the subtle theme of linguistic confusion mean for Captain Corelli’s Mandolin? Probably it helps highlight the way in which language isolates the different groups in the book, even though the outsider (the reader) can see underlying similarities in the characters. This means that our language barriers make us see each other as alien entities despite the fact that we all holler the same feelings and ideas into the air, which unfortunately come out as gibberish. As in the biblical quotation, our linguistic gaps cause us to see each other ‘in a mirror, dimly’. We are looking at ourselves, but get the impression of a strange and unknown creature. Can we hardly wonder, then, at all the trouble we cause on account of our own confusion? Until we learn the lesson of Corelli, linguistic variety will haunt us with misunderstandings and worse atrocities rather than with new and inspiring ways of perceiving our common reality. Cynthia Paz Gonzalo Riva Fernando Valdivieso