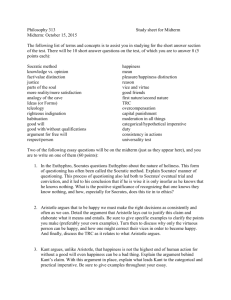

Ethics Paper

advertisement

Olson 1 Jacob Olson Dr. Marcus Varheagh Philosophy 101 6 December 2006 Aristotle and Kant’s Ethics Many philosophers have argued that stories gain their value through their correspondence to general truths that they harness or clarify in concrete form. Since philosophers can know these general truths directly, fiction and history are inferior to philosophy. Socrates, as presented by Plato, held such an extremist version of this position that he was ready to expel all poets from his ideal state, and replace their books with myths created by philosophers. Kant held a generally more complex theory of art, but he agreed with Socrates' view about the relationship of stories to moral philosophy. "Imitation," he wrote, "finds no place at all in morality, and examples serve only for encouragement, for example, they put beyond doubt the achievability of what the law commands, they make visible that which the practical rule expresses more generally, but they can never authorize us to set aside the true original which lies in reason, and to guide ourselves by examples"(Weardt 28). This position coincides well with the view, also common among moral philosophers, that moral truth is ultimately a matter of theory. As J. S. Mill put it, "the morality of an individual action is the application of a law to an individual case." If truths in the moral realm are laws, maxims, or doctrines, then stories can offer instantiations or illustrations of these doctrines (Douglas 9). Olson 2 On the other side of the table is the position that narrative is a free form and a rival of philosophy, capable of carrying moral meanings that are not associated with philosophical paraphrase. Hints of this latter view appear in Aristotle's Poetics. A manifesto is proposed against the Socratic piece of literature, and announces that the work will be "about poetry in itself and its various forms, and the capacity that each has" (Aristotle Ch. 9) By contrast, Socrates had treated poetry as a potential vehicle for philosophy and not as a genre "in itself." For Aristotle, imitation is natural, pleasurable, and instructive. Furthermore, poetry ought to realize its natural form to the greatest possible extent, shooting for real imitation. Aristotle believes that literature ought to show us what it wants to communicate, and not tell us. He knows that imitation is not just a clone, and that descriptive or narrative writing can contain meaning, even if the text never mentions actual ideas. The central principle of Kant's ethical theory is what he calls the Categorical Imperative. He offers several formulations of this principle, which he regards as all saying the same thing. They seem to say different things. First, there is the formulation Kant regards as most basic: "act only on that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should be a universal law" ( Ethics Updates). The test for the morality of an action that Kant expresses here is something like the following. Suppose that I am trying to decide whether or not to perform a particular action, say X. Then I must go through the following steps: 1. Formulate the maxim of the action. That is, figure out what general principle you would be acting on if you were to Olson 3 perform the action. The maxim will have something like this form: "in situations of sort S, I will do X." (For example: "in situations in which I am thirsty and there is water available, I will drink it," or "in situations in which I need money and know I can't pay it back, I will falsely promise to pay it back.") 2. Universalize the maxim. That is, regard it not as a personal policy but as a principle for everyone. A universalized maxim will look something like this: "in situations of sort S, everyone will do X." (For example: "in situations in which anyone is thirsty and water is available, that person will drink it," or "in situations in which anyone needs money and knows he or she cannot pay it back, he or she will falsely promise to pay it back. 3. Determine whether the universalized maxim could be a universal law, that is, whether it is possible for everyone to act as the universalized maxim requires. First example seems harmless, but Kant argues that the second maxim could not be a universal law: if everyone started making false promises, the institution of promising would disappear, so no one would be able to make false promises, since there would be no such thing as a promise to falsely make.) If the universalized maxim could not be a universal law, you have a perfect obligation not to perform the action. By treating others as mere means, treating them only as devices, we can use them to help us satisfy our desires, seems a clear enough notion; certain kinds of corporate and sexual relationships seem like clear examples of it. Kant's idea seems to be that we treat someone as an end only insofar as we act toward him or her in a way that he or she can understand as appropriate or justified: we should be able to explain our reasons in such a Olson 4 way that the person will see the reasonableness of acting in the way we propose. Thus, for example, Kant writes: "he who is thinking of making a lying promise to others will see at once that he would be using another man merely as a mean, without the latter containing at the same time the end in himself. For he whom I propose by such a promise to use for my own purposes cannot possibly assent to my mode of acting towards him, and therefore cannot himself contain the end of this action" (Ethics Updates) He is not saying that we should never treat others as means. Most of us probably couldn’t even survive if we didn’t. We treat farmers as means to supply us with food, builders as means to provide us with a place to stay instructors as means to help us get an education. What he is saying is that we shouldn’t treat others as means only. We should deal with others in ways such that they could accept the way we treat them. I do not treat the farmer as a means only because I am willing to pay him for the food he provides me, and he is willing to provide the food on those terms. I am respecting him as a being that sets his own ends, who determines for himself how he will act and interact with others. More generally, treating others as ends in themselves means not using force or deception or manipulation to get one’s own way. It means open, honest and respectful treatment of others. What is ruled out by this formulation, therefore, appears to be actions which treat others in such a way that they do not have the opportunity to consent to what we are doing. So we treat others as mere means when we force them to do something, or when we obtain their consent through compulsion or dishonesty. Olson 5 One of the main concepts of Aristotle’s essay, Nichomachean Ethics, is man’s pursuit of happiness. Aristotle’s opening sentence of the essay states: “Every Art and every inquiry, equally practice and pursuit, seem to be aimed at some good, on account of which it has been nobly said that the good is that at which all things aim.” There is no debate that the supreme Good is happiness; the debate arises over what exactly constitutes true happiness in life. I think that Aristotle is saying that happiness consists of a certain way of life, not of certain dispositions. A person’s true happiness will not come from their outlook on certain situations, their wealth, or their luck. True happiness, the aim of all things, comes from a person’s way of life. Aristotle also draws associates between being happy and being virtuous. Possessing the right virtues allows a person to live well. Since happiness is the activity of living well, the virtuous are more likely to live a happy life. I agree with Aristotle in that happiness is not merely an activity or outlook, but a way of life. Winning the lottery won’t make a person truly happy. They will be happy when they know that they are living their life in accord with their set of morals. To me, true happiness comes not from monetary wealth, academic achievements, or personal accomplishments. Happiness is when someone can say that their decisions are dictated by their morals, not their personal motives. To have your life guided strictly by a moral code, not by a desire for personal gain, would bring someone true happiness. If you live your life based solely on morals, you will find happiness in life no matter what happens because you are living life based what is truly right, not what is beneficial to you. Olson 6 According to Aristotle, such methods of ethical judgment are superior to the methods of philosophy. We cannot, he argues, judge particular cases by applying moral doctrines or definitions to them. "Such arguments have some validity, but truly the decision lies in the facts of life and deeds; for the authority lies in these" (Lawrence 77). Moral truth emerges from the concrete facts when we describe them thickly, by portraying them as part of a meaningful narrative. We ultimately gain the authority to judge only if we have perceived a particular case in careful, value-laden terms. Moral generalizations are indispensable as rules-of-thumb, since we lack sufficient time to describe every situation in detail. The foundation of ethical reasoning is the judgment of concrete particulars (situations that we can actually envision or experience). "Such matters depend upon the particular circumstances, and the decision lies with perception" (Lawrence 82). It is rare for a philosopher in any era to make a significant impact on any single topic in philosophy. For a philosopher to impact as many different areas as Kant did is extraordinary. His ethical theory has been extremely influential. Kant is the primary proponent in history of what is called deontological ethics. Deontology is the study of duty. On Kant's view, the sole feature that gives an action moral worth is not the outcome that is achieved by the action, but the motive that is behind the action. The categorical imperative is Kant's famous statement of this duty: "Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law" (Owens 11). Olson 7 Although there is no denying Aristotle’s genius, it is hard not to find his list of ethics presented in book in book IV somewhat dated, from our perspective at least. Although there is no denying ancient Greece’s influence on our concept of virtue, there is also no denying that Christian morals influence our virtues even more. As good as Ethics is, it is beginning to show its age more than 2300 years after it was written. In book IV, Aristotle discusses each of his virtues one by one. In my opinion, the most glaring omission from this list is the virtue of humility. In fact, Aristotle considers humility to be a vice. To me, in order for me to call someone virtuous they must not be arrogant or self centered. If someone possess all the virtues, but also has the perception that they are superior to everyone else, are they truly virtuous? Also missing from the list are other more modern Christian virtues; faith or belief, hope, and charity. I do agree that for a person to be truly virtuous they must have not just one or two, but all of the virtues. However two of his virtues, magnificence and magnanimity, can only be possessed by the wealthy and honorable. Does this mean that only the rich can be virtuous? Although there is something to be said for desires and way of life, I think that a person of lesser means, living a simpler life, would be better suited to live a truly virtuous life. A shepherd, living alone in a dug-out in the mountains, can’t be virtuous because he doesn’t show magnificence and magnanimity. Kant and Aristotle both respectively had brilliant views and theories on ethics. Each philosopher had respectable points and also some that were not so respectable. It is my belief that Aristotle, a god of philosophy in his own right, hit the nail on the head and Olson 8 had a better ethical theory and Kant. His explanations of virtue and moral truth and how they apply to the way of life are much more developed and applicable than Kant’s. Today, normative ethics bridges the gap between meta-ethics and applied ethics. It is the attempt to arrive at general moral standards that tell us how to judge right from wrong, or good from bad, and how to live moral lives. Normative ethics takes the positive concepts from both Aristotle (virtue ethicists) and Immanuel Kant (deontological ethicist) and creates the supposed ideal ethics we have today. Ethics has been applied to economics, politics and political science, leading to several distinct and unrelated fields of applied ethics, including business ethics and Marxism. American corporate scandals such as Enron and Global Crossings are illustrative of the interplay between ethics and business. Ethical inquiries into the fraud perpetrated by corporate senior executive officers are a growing trend. Ethics has been applied to family structure, sexuality, and how society views the roles of individuals; leading to several distinct and unrelated fields of applied ethics, including feminism. Ethics has also been applied to war, leading to the fields of pacifism and nonviolence. Olson 9 Work Cited Aristotle. Nichomachean Ethics. trans by W.D. Ross. eBooks@Adelaide, 2004. Aristotle. Poetics. trans by S. H. Butcher. Procyon Publishing, 1995. Barns, Jonathan. Aristotle and the Methods of Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Douglas, C.M. John Stuart Mill: A Study of His Philosophy. Edinburgh: Blackwood, 1995. Ethics Updates - Kant and Kantian Ethics. 10/18/06. http://ethics.sandiego.edu/theories/Kant/index.asp Hurthouse, Rosalind. On the Virtue of Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Lawrence, Gavin. Critique Aristotle and the Ideal Life. Philosophical Review: 1993. Owens, Karl. Kant’s Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Swanton, Christine. Virtue Ethics: Pluralistic View. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. Vogel, Stephen. The Philosophy of Aristotle: Literature and Religion. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Books, 1998. Weardt, Vander. The Socratic Movement. Ithaca: The Cornell University Press, 1994. Word Count: 2,420