Cat Litter Warning Signs

advertisement

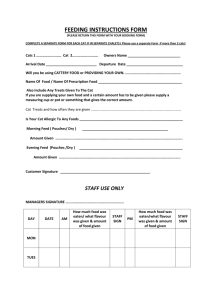

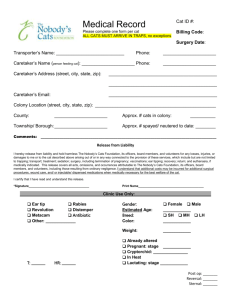

Cat Litter Warning Signs What the litterbox says about your cat’s health. Dusty Rainbolt There are a couple of natural laws that must be obeyed: What goes up must come down; and what goes in will eventually come out, at least in a healthy cat. What your cat deposits in his litterbox provides a virtual peek into the condition of his insides and a summary of his overall health. Litterbox contents provide warning signs that your cat has a problem and needs to see a veterinarian. Watch for Changes Start today by noting your cat’s litterbox habits. Frequently, the first sign that your cat might be struggling with a life-threatening disease is when his litterbox routine or contents suddenly change. Your little couch panther is hardwired for medical secrecy. While domestic cats are fierce predators for their size, they appear on the dinner menu to coyotes, foxes, and even dogs. In nature, drawing attention to illness is the equivalent of wearing a sign that reads, “Eat me.” Kitties put on a poker face and suffer in silence as a survival mechanism. So, what is normal? It varies from cat to cat. Going to the bathroom should be effortless and pain free. “Under normal circumstances a cat will pee once or twice a day,” says Drew D. Weigner, DVM, a board-certified feline specialist in the greater Atlanta area. “Some cats will go more, some less, but usually it will be the same amount. So, if they usually pee twice a day, and they suddenly go four times, that’s a change.” In addition to frequency, you should “watch for changes in the amount of urine or character of the stool,” says Michael Stone, DVM, American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine diplomat at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University. Also, keep an eye out for blood in urine or stool. (Using a white silica gel litter makes it easier to spot.) Sometimes, you don’t even need your eyes to detect changes; some will hit you right in the nose. “Nothing the cat puts in the litterbox smells good,” admits Beth Adelman, a certified cat behavior consultant with a practice in Brooklyn, N.Y. “You know what it smells like, and it’s not a good smell. But when it suddenly smells 10 times worse, that’s something to be concerned about.” Peeing Too Little One of the most critical changes to watch out for is your cat repeatedly attempting to use the box. “There are many reasons for frequently urinating small amount,” Weigner says. “It could indicate a urinary tract disorder, such as feline lower urinary tract disease, which includes bladder stones and crystals, idiopathic cystitis and infections.” FLUTD is a complex of disorders affecting the feline lower urinary tract. One common cause of FLUTD in cats under 10 years of age is feline interstitial cystitis (sometimes called feline idiopathic cystitis). FIC is one component of FLUTD, and can be difficult to diagnose and treat. Cystitis is any inflammation of the lining of the bladder. This painful condition might be caused by crystals, stones, bacterial infection or tumors. Idiopathic means we don’t know the cause. A cat with FIC or other urinary tract disorders who experiences pain while using the litterbox will often avoid it. He might be thinking, “That box hurt me. If I don’t go into it, I’ll be OK.” It’s a logical approach, at least from the cat’s perspective. “Even stress can cause cystitis,” says Cynthia Rigoni, DVM, owner of All Cats Veterinary Clinic in Houston. “Stressors like moving the furniture, tearing up the street in front of your house, a neighborhood stray teasing your cat through the window or the kids going off to school can manifest on your floor, walls, and pillows.” Rigoni treated a kitty named Torts whose human mom was studying to be a lawyer. “When the owner was preparing for her finals, she got wired up, so Torts got wired up,” Rigoni says. “He developed cystitis. There was microscopic blood in his urine. The bladder wall thickens.” After bringing home a litter of foster kittens, cat rescuer Susan Greene of Spencer, N.Y., noticed a difference in her cat Ivan’s litterbox behavior. The 10-year-old cat suddenly began urinating on objects, such as luggage and sweatshirts on the floor. Greene discounted the behavior as stress marking because of the kittens. Greene’s husband, however, noticed that Ivan was only passing droplets, and they rushed Ivan to the emergency clinic. X-rays showed that several very tiny bladder stones had completely blocked him. Ivan came home with an Elizabethan collar and a catheter. After his third but with blockages, Ivan underwent a perineal urethrostomy, a widening of the urethra. today, Ivan, is a thriving 15-year-old. Since his surgery, Ivan has experienced no further blockages. “So many times people thing it’s behavioral and they ignore it,” Rigoni says. But that can be a heartbreaking mistake. Had it not been for Ivan’s observant family, the story might have had a very different tragic ending. “Whenever a cat isn’t urinating, it’s a medical emergency,” Rigoni says. “If a cat can’t urinate, it can die of uremia within a 24to-36-hour period.” Weigner says if you notice your cat “going back and forth to the litterbox, crying while using the box, throwing up after using it or acting lethargic, take him to the veterinarian. If he’s peeing small amounts, go to the veterinarian first thing in the morning. However, not peeing at all is a real emergency that requires immediate action.” Peeing Too Much The opposite end of the urinary spectrum could indicate different but deadly health problems, as well. People assume what the cat eats and drinks dictates the quality of output, but according to Weigner, “What goes out actually dictates what comes in. Cats get dehydrated from peeing too much or from diarrhea.” Maybe your cat has started to pass copious amounts of urine. Weigner call this condition polydipsia polyuria. Polydipsia means drinking a lot; polyuria means peeing a lot. “Diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and kidney disease cause not only increased water intake, but also increased urine output,” Weigner says. “If you see increases in the amount of urine but also going more frequently, it’s time to go see the veterinarian. It’s usually pretty obvious.” According to stone, “Monitoring for changes in urine volume might allow the earlier detection of problems and be associated with a better treatment outcome.” Changing Postures Any change in habits is worth noting. Maybe your cat has started going to the bathroom standing up. Urine sprays the wall, or sometimes his feces lands on the floor. Maybe he’s going right next to the box. When Caralee Woods’ Siamese mix, Cassie, turned 16, she suddenly stopped using the litterbox. “I watched her approach the box, look at it as if wanting to use it, then use the area in front of it,” Woods says. Woods realized Cassie’s back legs weren’t cooperating. “It wasn’t comfortable for her to jump in the box and try to balance on shifting sand.” After a veterinary visit confirmed her suspicions, Woods provided pee pads at the location of Cassie’s mishaps. Problem solved. Frequently cats have arthritis in their hind ends, or they might have hip dysplasia, Rigoni says. “Ninety percent of cats over 5 have arthritis in their spinal column. They’re no flexible, so they can’t jump into the box like they used to even though they can still jump on the bed. They can’t hunch over any longer, either.” When buying a box for senior kitties, keep in mind that cats with achy joints need a low entry so they can climb in easily and high sides to keep the cat from peeing over the edge. An 18-or-31-gallon storage container with a low entrance cut out might be just what the veterinarian ordered. The poop on poop On the solid side of the litterbox, most cats will pass a stool for every meal they eat. Having bowel movements should be an easy process. “When it comes to stools, the consistency is the most important thing,” Weigner says. “If it doesn’t come out as a cylinder, it’s diarrhea,” he says. “Textures of pudding, cow flop or unformed stool are not normal. Three days of diarrhea means something’s up. They need to be seen by a veterinarian. It can be very minor. Parasites, stress or a change in diet could cause a temporary upset, but it could also be a symptom of a much more serious condition, such as diabetes, kidney failure, thyroid disease or inflammatory bowel disease.” Blood or mucus that looks like clear jelly in the stool indicates that something is up even if they don’t have diarrhea, he says. Seek immediate care if diarrhea and vomiting are present at the same time. Your cat might have ingested something toxic or might have an intestinal obstruction. Fresh blood or mucus in the stool might indicate colitis or parasites. “Change of color might occur when a new diet is fed, and this is generally or little concern,” Stone says. “A darkly-colored stool might suggest intestinal bleeding. If gastric or intestinal bleeding occurs, the intestinal tract will digest the blood and change the stool to a dark color, often with a tar-like consistency.” Cats also can suffer from constipation. “Constipation isn’t a disease,” Weigner says. “It’s a symptom of an underlying condition like obstruction, dehydration, painful defecation, impacted anal glands or a side effect of medication.” “It can be subtle,” Weigner says. “They’re dropping little pieces of stool around the house. Sometimes they throw up after they go to the bathroom (or after they attempt to go). Straining to go sometimes makes them nauseous.” If you notice your cat struggling to pass a stool, he needs to see his veterinarian. Never use a human enema on your cat because they contain sodium phosphate, which is toxic to cats. Don’t ignore kitty constipation, as chronic constipation can lead to megacolon, a chronically enlarged colon resulting from inability of the colonic muscles to contract. Reasons for litterbox changes abound, some minor, some major, so don’t selfdiagnose. Monitor your cat’s health by keeping an eye on his elimination activity. This knowledge will help you and your veterinarian spot serious disease, hopefully in the early, treatable stage.