Prevention and

management of preeclampsia and

eclampsia

A Reference Manual for

Health Care Providers

Copyright © 2011, Jhpiego. All rights reserved. The material in this document may be freely

used for educational or noncommercial purposes, provided that the material is accompanied

by an acknowledgement line.

Suggested citation: MCHIP. Prevention of eclampsia: A Reference Manual for Health Care

Providers. Baltimore: Jhpiego; 2011.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia

and eclampsia

A Reference Manual for Health Care Providers

2011

Maternal and Child Health Integrated Project

(MCHIP)

This project is made possible through support provided to MCHIP by the Office of Health, Infectious Diseases and Nutrition, Bureau

for Global Health, US Agency for International Development, under the Cooperative Agreement No. GHS-A-00-08-00002-00.

MCHIP is implemented by a collaborative effort between Jhpiego, Save the Children, John Snow, Inc (JSI), MACRO, Johns Hopkins

University Institute for International Programs (IIP), Program for Appropriate Technology for Health (PATH), Broad Branch

Associates (BBA), Population Services International (PSI), Collaborating Organizations: Communication Initiative (CI), CORE, and

others.

iv

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Table of contents

Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1

Understanding pre-eclampsia and eclampsia.................................................................. 5

Pathophysiology ................................................................................................... 5

Epidemiology of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia .......................................................... 6

Factors influencing maternal and perinatal outcomes ................................................ 7

Morbidity and mortality associated with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia ......................... 8

Identifying pre-eclampsia .......................................................................................... 11

Introduction ...................................................................................................... 11

Definition .......................................................................................................... 11

Screening .......................................................................................................... 12

Detecting hypertensive disorders in pregnancy ...................................................... 16

Prevention of pre-eclampsia and/or eclampsia ............................................................. 21

Primary prevention of pre-eclampsia..................................................................... 21

Secondary prevention (screening and detection) .................................................... 22

Tertiary prevention (management of severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia) ............... 23

Overview of interventions to prevent pre-eclampsia and eclampsia........................... 27

Management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia .............................................................. 29

Introduction ...................................................................................................... 29

Gestational hypertension ..................................................................................... 29

Mild pre-eclampsia - Gestation less than 37 weeks ................................................. 30

Mild pre-eclampsia - Gestation of 37 complete weeks or more ................................. 31

Severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia .................................................................... 31

Postpartum care................................................................................................. 38

Referral for tertiary level care .............................................................................. 38

Management during a convulsion / fit ......................................................................... 39

Stages of an eclamptic fit .................................................................................... 39

Management during a convulsion ......................................................................... 40

Differential diagnosis of convulsions ..................................................................... 41

Birth preparedness and complication readiness ............................................................ 45

Birth-preparedness plan ...................................................................................... 45

Complication-readiness plan ................................................................................ 46

References .............................................................................................................. 49

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

v

Acknowledgements

Susheela Engelbrecht led development of the learning materials, with technical assistance

and feedback from members of the MCHIP Training and Quality Assurance Task Force, one

of the five Task Forces formed under the Pre-Eclampsia/Eclampsia Technical Working Group.

Members of the task force include Patricia Gomez, Diane Sawchuck, Peter von Dadelszen,

Abdelhadi Eltahir, Frances Ganges, Ann Davenport, Deborah Armbruster, Nahed Matta,

Jeffrey Smith, Annette Briley, and Bridget Lynch. The writing team is grateful to Ahmet

Metin Gulmezoglu for review of this draft.

About MCHIP

vi

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Acronyms

BP

blood pressure

BPP

birth preparedness plan

CRP

complication readiness plan

dBP

diastolic blood pressure

DIC

disseminated intravascular coagulation

HELLP

Hemolysis, ELevated Liver enzymes, and low Platelet count

syndrome

HIP

hypertension in pregnancy

IUGR

intrauterine growth restriction

Magpie Trial

magnesium sulfate for prevention of eclampsia trial

MAP

mean arterial pressure

MCHIP

maternal and child health integrated project

MDG

Millennium Development Goals

RCT

randomized controlled trial

sBP

systolic blood pressure

STI

sexually transmitted infections

UTI

urinary tract infection

USAID

United States Agency for International Development

WHO

World Health Organization

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

vii

viii

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Introduction

Efforts such as the Safe Motherhood Initiative and the World Health Organization (WHO)

Making Pregnancy Safer Division and strategies to meet the United Nations Millennium

Development Goals (MDG) are supporting worldwide activities to reduce maternal and

newborn mortality. Despite these efforts, hundreds of thousands of women and babies die

or become disabled due to complications of pregnancy and childbirth every year (WHO,

1994).

Women die from a wide range of complications in pregnancy, childbirth or the postpartum

period. Most of these complications develop because of their pregnant status and some

because pregnancy aggravated an existing disease. The four major causes are severe

bleeding (mostly postpartum hemorrhage), infections (also mostly in the immediate

postpartum), hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (eclampsia), and obstructed labor. New

estimates show that the leading causes of maternal deaths are hemorrhage and

hypertension, which together account for more than half of maternal deaths (figure xx)

(WHO and UNICEF, 2010). Indirect causes, which include deaths due to conditions such as

malaria, HIV/AIDS and cardiac diseases, account for about one fifth of maternal deaths.

Regional estimates show that hemorrhage and hypertension are among the top three

causes of deaths in both South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of

maternal deaths occur (WHO and UNICEF, 2010). Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia may also

occur in the immediate post-partum period and is referred to as "postpartum preeclampsia." The most dangerous time for the woman is the 24–48 hours postpartum and

careful attention should be paid to pre-eclampsia signs and symptoms (Manjuluri et al,

2005).

Figure xx. Global estimates of the causes of maternal deaths, 1997-2007

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

1

Ten percent of all pregnancies are complicated by hypertension (HTN) (Craici et al, 2008).

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia account for about half of these cases worldwide and have been

recognized and described for years despite the general lack of understanding of the disease

(Roberts et al, 2001). The fetal mortality rate associated with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

varies from 13-30%, primarily due to premature delivery and its complications (Gabbe,

2007). Placental infarcts, abruptio placentae, and intrauterine growth restriction also

contribute to fetal demise (Gabbe, 2007). Maternal death risk associated with preeclampsia and eclampsia is approximately 1.8%, in high resource settings, and up to 14%

in settings with low resources and lack of facilities required for supportive

management. Higher mortality rates are associated with women who have multiple

convulsions/fits outside the hospital and those without antenatal care (Rivers, 1996).

Fortunately, simple, low-cost interventions are available to prevent most cases of eclampsia

and to manage them when they occur. Providers at all levels must be able to identify preeclampsia and eclampsia and know how to respond. Timely diagnosis and effective initial

management can reduce morbidity and the risk of maternal, fetal, and newborns deaths

associated with severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Once providers identify pre-eclampsia

and eclampsia, they must be competent to provide effective initial management and ensure

timely referral for cases that cannot be managed at their facility level.

To facilitate access to important maternal technologies, countries must have the political will

and ensure that the following are in place:

National guidelines that reflect state-of-the-art and evidence-based interventions for

prevention, identification and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Policies that promote access to important technologies for prevention, identification

and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia at all levels along the continuum of

care

Training infrastructure that promotes pre-service education and periodic updates and

refresher training for all health workers in prevention, identification and management

of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia at all levels along the continuum of care

Service delivery systems that ensure quality and promptness of response for women

with severe pre-eclampsia/ eclampsia

Logistics systems that ensure availability of necessary resources (equipment,

supplies, medications - magnesium sulphate and calcium gluconate) and

consumables for infection prevention and injection safety

Supervision and monitoring systems that assure quality and ensure transfer of

learning to the work site

A service delivery model that promotes education and knowledge sharing with

women, families and communities about the risks, signs and symptoms, and how to

respond when the woman presents with signs or symptoms of pre-eclampsia and

eclampsia

Links between communities and health care facilities that ensure that the woman

receives timely and appropriate care

Ongoing research in various settings continues to identify the best approaches for

preventing and managing eclampsia and its complications. By developing national

guidelines, training health care providers, improving work environments, and supporting the

development of improved access to care, more women will have access to life-saving

interventions that reduce morbidity and mortality associated with pre-eclampsia and

eclampsia.

2

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

About the learning materials

MCHIP developed a learning package on the prevention and management of pre-eclampsia

and eclampsia consisting of a reference manual, participant’s notebook, and facilitator’s

guide. This learning package was developed for use by clinical health workers, nurses,

midwives, and physicians providing care during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum.

These documents comprise a set and should be used together. These resources are

distinguished within the series by a corresponding icon located at the top of the right hand

page:

Reference manual

Facilitator’s guide

Participant’s notebook

This course is designed to be utilized for in-service training, with the overall objective of

providing updates about prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia use

to equip nurses, midwives, physicians, trainers and clinical health workers to carry out the

following:

Provide safe, respectful, culturally sensitive, and friendly care to women, newborns, and

their families. Women and families will then be more likely to utilize the health care

system with confidence because they know they will receive competent, compassionate

care.

Follow an evidence-based protocol for prevention, identification, and management of

pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, including clear guidelines on when to refer women with

complications, ensuring timely action is taken.

Provide greater protection from infection for their clients and exercise of universal

precautions for themselves.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

3

4

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Understanding pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Pathophysiology

Cause

Pre-eclampsia is a pregnancy-specific syndrome, recognized, even by Hippocrates, as a

leading cause of maternal and perinatal mortality. The condition’s former name, “toxemia of

pregnancy,” was based on a theory that a toxin produced in a pregnant woman’s body

caused the disease. The cause of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia remains unknown, though

experts have proposed multiple theories to explain their cause, resulting in confusion and

myths surrounding both etiology and management. The main etiologic theories

include abnormal trophoblastic invasion, coagulation abnormalities, vascular endothelial

damage, cardiovascular maladaptation, immunologic phenomena, genetic predisposition,

and dietary deficiencies or excess (Craici et al, 2008).

Pathophysiologic changes

In normal pregnancies, blood volume increases 30 to 50%, peripheral vascular resistance

decreases, progesterone induced arterial dilatation occurs, fibrinogen is increased, and

factor XIII (fibrin stabilizing factor) is decreased. The following pathophysiologic changes

are associated with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia:

Blood pressure begins to rise after 20 weeks of pregnancy

Perfusion is decreased to virtually all organs, which is secondary to intense vasospasm

due to an increased sensitivity of the vasculature to any pressor agent

Perfusion to the kidneys is decreased, resulting in sodium retention that leads to loss of

intravascular plasma volume, increased extracellular volume (edema) and increased

sensitivity to pressor agents

Loss of normal vasodilation of uterine arterioles results in decreased placental perfusion

Decreased intravascular volume results in increased viscosity of the blood and a

corresponding rise in hematocrit, and activation of the coagulation cascade, especially

platelets, with microthrombi formation

HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome is

sometimes associated with severe pre-eclampsia and results from activation of the

coagulation cascade.

Disease progression

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are part of the same disorder with eclampsia being the severe

form of the syndrome. Gestational hypertension may progress from a mild hypertensive

disorder to a life-threatening condition, as follows:

hypertension without proteinuria or edema

mild pre-eclampsia

severe pre-eclampsia

eclampsia

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

5

While pre-eclampsia is usually a progressive disease, the rate of progression and the

occurrence of catastrophic complications such as eclampsia, cerebrovascular accident,

severe HELLP syndrome, pulmonary edema or renal failure are difficult to predict. In some

cases, mild pre-eclampsia sometimes progresses to severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

very suddenly with little or no warning. In other cases, hypertension or proteinuria are

absent when a woman begins having eclamptic convulsions/fits. Eclampsia can occur during

the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum periods; and ninety percent of eclampsia

cases occur after 28 weeks' gestation (Gabbe, 2007).

HELLP syndrome is a group of symptoms that occur in pregnant women who have:

H -- hemolysis

EL -- elevated liver enzymes

LP -- low platelet count

HELLP syndrome occurs in approximately 10% of pregnant women with pre-eclampsia or

eclampsia. Many women have high blood pressure and are diagnosed with pre-eclampsia

before they develop HELLP syndrome. However, in some cases, HELLP symptoms are the

first warning of pre-eclampsia and the condition is misdiagnosed as hepatitis, gallbladder

disease, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

The exact cause of HELLP is unknown, but general activation of the coagulation cascade is

considered the main underlying problem. Fibrin forms cross-linked networks in the small

blood vessels. This leads to a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia: the mesh causes

destruction of red blood cells as if they were being forced through a strainer. Additionally,

platelets are consumed. As the liver appears to be the main site of this process,

downstream liver cells suffer ischemia, leading to periportal necrosis. Other organs can be

similarly affected. HELLP syndrome leads to a variant form of disseminated intravascular

coagulation (DIC), leading to paradoxical bleeding, which can make emergency surgery a

serious challenge.

Symptoms include:

Headache

Nausea and vomiting that continues to get worse

Upper abdominal pain / upper abdominal tenderness on palpation

Vision problems

The woman's liver may hemorrhage and permanent liver damage may occur if delivery is

delayed. Such damage can lead to death. Up to thirty-five percent of women with HELLP

die. The death rate among babies born to mothers with HELLP syndrome varies and

depends on birth weight and the development of the baby's organs, especially the lungs.

Epidemiology of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

“Risk factors” should not be used to predict complications. The system of

risk categorization, or the “risk approach”, previously used for selecting

women for specialized management is not useful, because evidence shows

that many women categorized as “high risk” do not actually experience a

complication, while many women categorized as “low risk” do.

6

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Numerous maternal factors may predispose to the disorder; these may be genetic,

behavioral, or environmental. While there are maternal factors predisposing to preeclampsia, a population based approach should be used where all pregnant women are

considered “at risk” of developing pre-eclampsia should be taken.

Factors that may predispose a woman to pre-eclampsia and therefore the risk of eclampsia

include (Roberts et al, 2001; WHO, 1994; WHO and UNICEF, 2010):

Maternal factors

Women with a family history of pre-eclampsia, prior pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Women with a history of poor outcome of previous pregnancy, including intrauterine

growth restriction, abruptio placentae, or fetal death

Preexisting medical conditions - renal disease, thrombophilias-antiphospholipid

antibody syndrome, protein C deficiency and protein S deficiency, antithrombin deficiency,

vascular and connective tissue disorders, diabetes, gestational diabetes, systemic lupus

erythematosus, increased testosterone, increased insulin resistance, increased blood

homocysteine concentration

Age: Teen pregnancy / Women who are older than 35 years

Lower socioeconomic status

Primigravida (especially young teenagers and women over 35 years)

Primipaternity (first pregnancy with the male partner)

Obese women (BMI > 30)

Women with essential or renal hypertension

Black women or women of African descent

Hydatidiform mole

Fetal factors

Hydrops fetalis

Multifetal gestations

Most traditional risk factors are associated with attributes of the woman or the

pregnancy/fetus. One hypothesis on the causes of pre-eclampsia is immune maladaptation.

Support for this hypothesis comes from epidemiological studies that show that:

the risk for developing pre-eclampsia decreases with the length of exposure to the sperm

that will ultimately fertilize the woman’s egg (Marti et al, 1977)

although pre-eclampsia is generally thought of as a syndrome of first pregnancies, the

protective effect of multiparity is lost with change of partner (Robillard et al, 1999)

men who fathered a pre-eclamptic pregnancy were nearly twice as likely to father a preeclamptic pregnancy in a different woman, regardless of whether she had already had a

pre-eclamptic pregnancy or not (Roberts et al, 2001).

Factors influencing maternal and perinatal outcomes

Pre-eclampsia is a major obstetric problem leading to substantial maternal and perinatal

morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially in low resource settings. Positive outcomes

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

7

depend on how soon a diagnosis is made and how quickly effective treatment is provided.

Maternal and perinatal outcomes in pre-eclampsia depend on maternal, community, and

health care factors (WHO, 2008).

Maternal factors influencing maternal and perinatal outcomes: These include health issues

the woman may have that make the disease worse.

In general, maternal and perinatal outcomes are usually favorable in women with mild

pre-eclampsia developing beyond 36 weeks’ gestation who have no other pre-existing

medical disorders.

By contrast, maternal and perinatal morbidities and mortalities are increased in women

who develop the disorder before 33 weeks’ gestation, in those with pre-existing medical

disorders, and in those receiving care in low resource settings.

Community factors influencing maternal and perinatal outcomes: These are characteristics

of the community that that affect whether and how the woman seeks care.

Lack of awareness about signs and symptoms of pre-eclampsia, severe pre-eclampsia and

eclampsia and the importance of early and regular antenatal care

Transportation barriers particular for obstetric emergencies.

Low socioeconomic status including lack of access to information and low literacy levels

Financial hardship and inability to pay for transport and medical care

Community distrust of health care personnel

Cultural barriers

Health service factors influencing maternal and perinatal outcomes: These are

characteristics of health services that affect the kind of care that women receive.

Inadequate availability and access to antenatal care

Failure to monitor blood pressure and urine during antenatal care

Failure to counsel women and families about dangerous symptoms of severe preeclampsia and the importance of regular antenatal care

Delay in referral of women with symptoms and signs of severe pre-eclampsia or

eclampsia

Lack of a clear-cut management strategy/clinical protocols for dealing with pre-eclampsia

and eclampsia

Inadequately trained staff to treat women with severe eclampsia or eclampsia

Delay in identification and management of severe pre-eclampsia

Lack of proper equipment and drugs to treat pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Morbidity and mortality associated with pre-eclampsia and

eclampsia

Effects on the woman

These include:

Respiratory problems (asphyxia, aspiration of vomit, pulmonary edema, bronchopneumonia)

Cardiac problems (heart failure)

8

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Effects on the brain (hemorrhage, thrombosis, edema)

Renal complications (acute kidney failure)

Hepatic disease (liver failure or hemorrhage)

HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count)

Coagulopathy (clotting/coagulation failure)

Visual disturbances (temporary blindness due to edema of the retina)

Injuries during convulsions/fits (fractures)

Abruptio placentae

Stroke

Death

Risk of pre-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancies

Long-term cardiovascular morbidity

The main causes of maternal death in eclampsia are intracerebral hemorrhage, pulmonary

complications, kidney failure, liver failure and failure of more than one organ (e.g. heart +

liver + kidney).

Effects on the fetus

These include:

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)

Preterm delivery

Hypoxia

Neurologic injury

Perinatal death (1–2%)

Long-term cardiovascular morbidity associated with low birthweight (fetal origin of adult

disease)

Hypoxia may cause brain injury if severe or prolonged, and can result in physical and/or

mental disability.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

9

10

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Identifying pre-eclampsia

Introduction

Pre-eclampsia is a progressive condition that can lead to stroke, kidney or liver damage,

blood-clotting problems, and pulmonary edema. Eclampsia is commonly defined as the new

onset of convulsions and/or unexplained coma during pregnancy or postpartum in a woman

with signs or symptoms of preeclampsia. However, eclampsia in the absence of

hypertension and/or proteinuria does occur.

The antenatal onset of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia is, by definition, after the 20th week of

pregnancy. Most cases of eclampsia present in the third trimester of pregnancy, with about

80% of eclamptic seizures occurring intrapartum or within the first 48 hours following

delivery. Rare cases have been reported prior to 20 weeks' gestation or as late as 23 days’

postpartum. Other than early detection of pre-eclampsia, no reliable test or symptom

complex predicts the development of eclampsia.

Mild pre-eclampsia may progress to severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia very suddenly with

little or no warning. In addition, women with pre-eclampsia do not feel ill until the condition

is severe and the disease is life threatening. Early detection by regular antenatal monitoring

and careful follow-up of those with mild pre-eclampsia is therefore essential for the early

diagnosis and treatment of severe pre-eclampsia.

Definition

The definition of hypertension during pregnancy has changed over the years:

In the past it has been recommended that an incremental increase of 30 mm Hg systolic

or 15 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure be used as a diagnostic criterion, even when

absolute values remain <140/90 mm Hg

More recently, the diagnostic criterion for gestational hypertension is based on a diastolic

blood pressure reading of 90mmHg or more

Some use mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 90mmHg or more in the second trimester. MAP

appears to be a better predictor for pre-eclampsia than systolic BP (sBP), diastolic BP

(dBP), or increased BP (Cnossen et al, 2008). MAP can be calculated as follows:

MAP ≈ dBP + [1/3 (sBP-dBP)]

or equivalently

MAP ≈ 2/3(dBP) + 1/3 (sBP)

Blood pressure measurements in the first and second trimester at the first

Blood

pressure

measurements

for with

healthy

normotensive

womendo

innot

thehelp

first

antenatal

visit for

healthy women

normal

blood pressures

12

and

second

trimester

do

not

help

predict

pre-eclampsia.

???Ref

predict pre-eclampsia (Hofmeyr and Belfort, 2009).

The diagnostic criteria for pre-eclampsia are diastolic blood pressure reading of 90mmHg

or more, with proteinuria (greater than 1+), after 20 weeks gestation.

Table XX provides an overview of diagnostic criteria for the different hypertensive disorders

in pregnancy.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

11

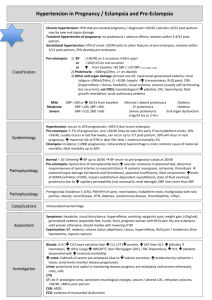

Table XX. Differential diagnosis of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

Diagnosis

Chronic hypertension

Diagnostic criteria

Diastolic BP 90 mm Hg or more prior to the first 20

weeks of gestation

Women with chronic hypertension

Any of the following are seen after 20 weeks’

gestation:

Pre-eclampsia superimposed on

chronic hypertension

- New or worsening proteinuria

- Sudden increase in BP in a woman whose

hypertension has previously been well controlled

- One or more adverse conditions associated with

pre-eclampsia and/or eclampsia

Two readings of diastolic BP 90 mm Hg or more but

below 110 mm Hg 4 hours apart after 20 weeks

gestation, no proteinuria.

Postpartum:

Gestational hypertension

- Transient hypertension of pregnancy if preeclampsia is not present at the time of delivery and

blood pressure returns to normal by 12 weeks

postpartum (a retrospective diagnosis) or

- Chronic hypertension if the elevation persists

beyond 12 weeks postpartum.

Mild pre-eclampsia

Two readings of dBP 90 mm Hg or more but below

110 mm Hg 4 hours apart

Proteinuria up to 2+

Severe pre-eclampsia

dBP 110 mm Hg or more

Proteinuria 3+ or more

A pregnant woman or a woman who has recently

given birth is found unconscious or having convulsions

(fits)

Eclampsia

dBP 110 mm Hg or more

Proteinuria 2+ or more

dBP = diastolic BP

sBP = systolic BP

Screening

Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are a major contributor to maternal mortality

worldwide. With standard refocused antenatal care, providers can detect blood pressure

elevation and the presence of proteinuria, ensure initiation of appropriate management

at the appropriate level of care, and prevent many of these deaths. Improved detection and

care should lead to a better outcome. If a woman develops hypertension, and/or

proteinuria, providers will need to closely monitor her and encourage her to give birth in a

health facility with skilled birth attendants.

Edema of the feet and lower extremities is not

considered a reliable sign of pre-eclampsia.

12

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Detecting proteinuria

The presence of proteinuria changes the diagnosis from gestational hypertension to preeclampsia. Detection of proteinuria is therefore key for making a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia.

Once pre-eclampsia has been diagnosed, it would require a considerable increase in

surveillance, often including admission. The social and financial repercussions of this for the

woman and the economic consequences for the healthcare system are considerable. It is

therefore important that tests for proteinuria are accurate.

Although proteinuria is most commonly associated with pre-eclampsia or eclampsia, a

woman's urine can test positive for protein if she is severely anemic, has kidney disease, or

has a UTI, or if the urine has been contaminated by blood (or if she has schistosomiasis),

vaginal discharge, or amniotic fluid. Urine tested for protein should therefore be a clean

catch, midstream specimen of urine. Vaginal secretions and discharge are common in

pregnancy and, if mixed with urine, give a positive test for protein. To avoid this, it is

important that:

-

The vulva is cleaned with water

-

The labia minora are spread

-

While urine is being passed, the middle part of the stream is caught in a clean

container.

Methods for measuring proteinuria differ from country to country and may vary by type of

resources available at the facility. Methods to evaluate proteinuria include:

Quantitation of a timed collection: This has been the gold standard for many decades

and is expressed as the amount of protein excreted in the urine per unit time. Twenty

four-hour specimens have been traditionally used, but more recently 12-hour collections

(and even 2-hour collections) have been validated (Hofmeyr and Belfort, 2009).

Urinary protein:creatinine ratio: This is used in some institutions instead of a timed

protein collection. A review conducted by Côté et al showed that the spot

protein:creatinine ratio is a reasonable “rule-out” test for proteinuria of 0.3 g/day or

more, among otherwise healthy women with gestational hypertension with or without

proteinuria on dipstick. However, they did not advocate use of the spot protein:creatinine

ratio or spot albumin:creatinine ratio for monitoring or quantifying proteinuria in

pregnancy (Côté et al, 2008).

Urine dipsticks: Urinalysis by visual reagent strip tests is widely performed in antenatal

clinics and in the community by various health professionals. A review by Waugh et al

(2004) showed that significant proteinuria, with point-of-care urine dipstick analysis,

cannot be accurately detected or excluded at the 1+ threshold and is not recommended

for diagnosing pre-eclampsia.

Dipstick method:

-

The end of the stick is dipped into the urine and excess shaken off by tapping the

stick on the side of the container

-

The result is then read by comparison with the color chart on the label at the

time indicated on the dipstick container.

Boiling urine: Boiling urine was widely used before dipsticks were widely available. Some

facilities may still use this method to test for protein in the urine.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

13

Boiling method:

-

Boil the top half of the urine in a test tube

-

Compare the top half of the urine with the unboiled bottom half (the boiled part

may become cloudy)

-

Add 1–2 drops of 2–3% acetic acid. Do this even if the urine has not become

cloudy

-

If, after adding the acetic acid, the boiled part of the urine remains cloudy,

protein is present in the urine

-

If the boiled urine was not cloudy to begin with, but becomes cloudy when acetic

acid is added, this is another indication that protein is present

-

If cloudy urine becomes clear when acetic acid is added, protein is not present.

While the measure of proteinuria is a poor predictor of either maternal or fetal complications

in women with pre-eclampsia (Thangaratinam et al, 2009), it remains one of the criteria for

the diagnosis of pre-eclampsia. Further work is needed to compare the different methods to

evaluate proteinuria in the management of pregnant women with hypertension, particularly

with respect to accuracy of diagnosis and the effect on inappropriate admissions and

discharges.

REMEMBER:

Because of changes in metabolism during pregnancy, the pregnant woman will spill

some protein in her urine and this is normal, as long as it does not exceed 1+.

Although proteinuria is most commonly associated with pre-eclampsia or eclampsia, a

woman's urine can test positive for protein if she is severely anemic, has kidney

disease, or has a UTI, or if the urine has been contaminated by blood (or if she has

schistosomiasis), vaginal discharge, or amniotic fluid.

The woman may have pre-eclampsia/eclampsia AND other conditions that may cause

proteinuria.

Detecting hypertension

BP readings are prone to inaccuracy due not only to observer and device error, but also to

variability of blood pressure and to rise in BP caused by anxiety/fear due to the effects of

attendance at the clinic (white-coat hypertension) (Higgins and de Swiet, 2001).

Simple measures to reduce observer error when taking BP measurements:

14

Choose the correct cuff size.

-

The cuff must be at least 2–3 cm (1 inch) above the elbow and should encircle at

least three–fourths of the circumference of the arm; otherwise, a false high

reading will be obtained.

-

The length of the bladder on the device should be 80 percent of the

circumference of the upper arm. This means that heavy or very muscular people

with thick arms need a larger bladder.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Figure xx. Bladder on the BP device

Wrap the cuff firmly around the upper arm.

Do not kink or twist the tube on the cuff. Make sure that the stethoscope fits into

your ears firmly and snugly.

If a mercury blood pressure machine is used, it must be in the vertical position, and

your eyes must be approximately at the same level as the top of the mercury column

or the reading will not be accurate.

If an aneroid manometer is used, place the manometer in your direct line of sight.

Systolic blood pressure is taken at the point at which the arterial sound appears.

Diastolic blood pressure is taken at the point at which the arterial sound disappears.

Simple measures to reduce device error when taking BP measurements:

Measurements should be made with a mercury sphygmomanometer; in centers

where the use of mercury has been banned for clinical purposes, the mercury

sphygmomanometer will have to be replaced by an electronic device that has been

validated for pregnancy.

The sphygmomanometer should be regularly calibrated

Aneroid Manometer

Check that the needle

is at the zero mark at

the start and the end

of the measurement.

Figure xx. Aneroid manometer

Check to see that the screw valve on the ball works properly before using the BP

machine.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

15

Pump up the bladder and watch for any air leaks. If the mercury column or aneroid

needle does not rise steadily as the ball is pumped, suspect a leak.

Simple measures to reduce variability of BP measurements:

Remove all tight clothes from around the arm. Tight clothes may partially block the

artery and give a false low reading.

The woman should not smoke or drink alcohol or coffee within 15 minutes of a blood

pressure measurement.

Make sure that the woman is as relaxed and comfortable as possible.

It is better if she rests for several minutes in that position before the measurement.

Ask her not to talk during the measurement.

Blood pressure should always be checked in the sitting position (BP will be highest in

the sitting position, somewhat lower when she lies supine, and lowest when she lies

on her side). The elbow (brachial artery) should be at the level of the heart.

-

She should sit with her back supported and her elbow at about the level of her

heart with her arm supported.

-

Her legs should not be dangling. Her feet should be supported or on the ground.

If the woman cannot sit, take the BP with her lying tilted to the left side.

-

Lying on the back is not a good position because the weight of the gravid uterus

exerts pressure on the inferior vena cava, thereby causing a drop in blood

pressure.

-

When BP is checked with the woman in left lateral recumbent, the superior arm

has 10-12 mmHg lower BP than the inferior arm

REMEMBER:

The normal BP is between 80/60 mmHg and 140/90 mmHg

When the pre-pregnancy BP is not known, the BP taken before 20

weeks is considered the woman's normal BP

Because of changes in cardiac output and blood volume, hormonal

changes which mediate a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance,

smooth muscle-relaxing effect of progesterone, and heat production by

the foetus, the BP will have some normal variations during pregnancy:

- Systolic and diastolic BP begin to fall in the 1st trimester, decreasing

until mid-pregnancy and gradually return to non-pregnancy baseline

by term

- There is a slight fall in systolic and considerable decrease in diastolic

later in gestation

Detecting hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

At every antenatal and postnatal visit:

1. Take a targeted symptom history. ASK the woman if she has had any of these

symptoms: epigastric pain (heartburn), headaches, or visual problems (double vision,

partial vision, rings around lights). Note that these are the danger signs the pregnant /

postpartum woman should herself be aware of and watch for.

2. Take the blood pressure at every visit.

16

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

If the diastolic BP is >90 mmHg, check that the BP cuff is the right size and that the

BP machine is functioning properly.

If there are no problems with the BP cuff size and machine, have the woman lie on

her left side for 20 minutes, then recheck it again with her sitting up

–

If the blood pressure is normal, educate the woman about danger signs and have

her return in two weeks for a BP check

–

If the blood pressure is still elevated, check a midstream urine sample for protein

and plan to check the BP again in 4 hours.

–

If the BP is still elevated 4 hours after the first reading, this is considered

hypertension.

3. Take a good personal and family history of:

Epilepsy

Hypertension

Renal or heart disease

Cerebro-vascular accident (CVA)

4. Check urine for protein at all visits after 20 weeks of pregnancy. Proteinuria is defined as

the presence of 300 mg or more of protein per liter in a clean catch, midstream

specimen of urine. Usually proteinuria follows a rise in blood pressure, but occasionally

it is the first sign of the disease.

If there is greater than 1+ protein in the urine:

–

Verify that the sample was a mid-stream/clean-catch sample

–

Check for sexually transmitted infections (STI) (especially if the woman has

abundant vaginal secretions). If the woman has an STI, treat according to cause

and following protocols.

–

Blood or white blood cells in the urine may cause a false positive test for

proteinuria because both blood and white blood cells are proteins. Rule out a

urinary tract infection, schistosomiasis (in endemic areas), and kidney infections.

If the woman has an UTI, schistosomiasis, or kidney infection, treat according to

cause and following protocols.

–

Rule-out anemia: Check haemoglobin (if there is a laboratory) or check for signs

of anemia; if the woman has moderate anemia, treat appropriately and rule out

hookworm and malarial infections; if the woman has severe anemia (<7 gm/dL),

refer her to a hospital/doctor.

–

If the woman’s blood pressure is elevated and she has protein in her urine

(>1+), check the biceps and/or patellar reflexes.

5. Test the woman’s biceps and/or patellar reflexes if the woman’s blood pressure is

elevated and she has protein in her urine (>1+).

Testing reflexes is part of an examination of the nervous system. It is very helpful

for midwives to know how to test a few basic reflexes on adults. Hyper-reflexia can

indicate many diseases of the nervous system or edema of the brain (cerebrum) in a

pregnant woman. A woman with cerebral edema is very likely to develop

eclampsia (convulsions).

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

17

Using a Reflex Hammer

A reflex hammer is used to check the deep tendon reflexes. Once you are

experienced, you may be able to use your fingers, the side of your hand, your

knuckles, or the head of a stethoscope instead. For beginners (learners), it may be

helpful to use a reflex (percussion) hammer.

1. Hold the hammer loosely between your thumb and index finger.

2. Bring the hammer down onto the tendon in a rapid, smooth movement.

3. Tap quickly and firmly.

4. Lift the hammer back up quickly.

5. Watch for how fast the response is. It is the speed of the response, not how

far the limb moves, that tells you if her reflexes are normal.

Reflexes are usually given a grade of 0 to +4. The scale of grading is:

0

+1

no response

low but within normal response

+2

average or normal response

+3

brisker than average

+4

very brisk, hyperactive, abnormal, may have rhythmic tremors (clonus)

When checking reflexes, always check both sides (both arms or both legs). Check

that the response is similar on both sides. The biceps and patellar reflexes are the

common ones to use when looking for pre-eclampsia in pregnant women.

Biceps Reflex

1. Bend the woman's arm about halfway.

2. With your fingers, feel for her tendon on the inside of her elbow (antecubital

fossa). If it is difficult to locate, move her arm up and down while feeling. You will

notice a cord-like tendon.

3. If the woman is lying down, the bed will support her arm. If she is sitting up, you

will need to support her arm on yours. Place your thumb on the tendon.

Figure XX. Biceps Reflex Testing

Adapted from: Marshall, M.A., Buffington, S.T. Life-saving skills manual for midwives. 3rd

edition. Washington, DC: American College of Nurse Midwives (ACNM), 1998

18

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

4. Strike your thumbnail, which is positioned over the tendon. This causes the

biceps muscle to contract. You may or may not see the slight contraction at the

woman's elbow.

5. You will be able to feel the response from the tendon through your thumb. You

can grade the response by how fast you are able to feel the reflex response. You

will need to check many reflexes before you develop an awareness of what is

normal. Check your family, friends, and all of your clients to gain experience.

Patellar Reflex

1. Have the woman sit on the examining table or couch. Her legs should hang

freely.

2. Feel for her tendon right below the kneecap (patella). If it is difficult to locate,

move her lower leg a little while feeling at the same time.

Figure XX. Patellar Reflex Testing, seated patients

Adapted from: Marshall, M.A., Buffington, S.T. Life-saving skills manual for midwives. 3rd

edition. Washington, DC: American College of Nurse Midwives (ACNM), 1998

3. Strike the tendon with a quick, firm tap and lift up immediately. You may also

use the side of your hand or your knuckle to tap the tendon.

4. Tapping the tendon will cause the quadriceps muscle to contract, causing the

lower leg to move.

5. The patellar reflex can also be tested with the woman lying in bed. Place one

hand under the leg, supporting it, and tap.

6. If the woman is tense and contracting her muscles, you will not get an accurate

test of her reflexes. You may need to talk to her and keep her attention away

from what you are doing.

If the reflexes are brisk (+3 or +4), refer her to a hospital/doctor.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

19

Remember:

20

A woman with severe pre-eclampsia who has hyper-reflexia (+3 or +4) is very ill.

She must be properly stabilized and transferred to a doctor/Level 3 facility as

quickly as possible.

Care of women with pre-eclampsia can save the lives of both the woman and

fetus.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Prevention of pre-eclampsia and/or eclampsia

Primary prevention of pre-eclampsia

By definition, primary prevention can help to avoid the development of a disease. Primary

prevention is difficult to achieve for pre-eclampsia because the cause is not well understood

and most factors associated with it are difficult to avoid or manipulate. Nevertheless, there

are certain interventions that can serve to prevent pre-eclampsia.

Prevention of too early and too late pregnancies with family planning

Pre-eclampsia is unique to pregnancy, and adolescent and older (more than 35 years of

age) women are at higher risk of pre-eclampsia, therefore prevention of high risk

pregnancies will prevent pre-eclampsia (Dekker and Sibai, 2001). Of course, women will

want to have children and cannot indefinitely wait for pregnancy. However, family planning

can help to delay the first pregnancy until the woman is at least 20 or 21 years of age; can

limit pregnancies beyond 35 years of age if women no longer want to continue having

children; and can ensure adequate spacing between pregnancies to allow the woman to

recover between pregnancies.

Prevention and/or treatment of obesity

Obesity is a definite risk for developing gestational hypertensive disorders, including preeclampsia. Obesity has a strong link with insulin resistance. The exact mechanisms by which

obesity/insulin resistance are associated with an increased risk for pre-eclampsia are not

completely understood. Prevention of or effective treatment of obesity, or both, could result

in a substantial decrease in its frequency.

Overweight and obese women should have counseling before pregnancy so that they are

aware of the risks and can try to modify their weight before pregnancy. Once an overweight

or obese woman is pregnant, she should eat a healthy, well-balanced, and monitored diet,

and try to limit weight gain to 7-11.5 kg (for BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2) or 5-9 kg (for BMI ≥ 30

kg/m2) (Rasmussen et al, 2009).

Prevention of IUGR

Pre-eclampsia increases the risk for intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). Having a low

birthweight as a consequence of IUGR has also been identified as an important risk factor of

the so-called insulin resistance syndrome in adult life. Prevention of pre-eclampsia and IUGR

could therefore, at least theoretically, contribute to primary prevention of pre-eclampsia

(and IUGR) in the next generation (Dekker and Sibai, 2001).

Smoking

Cigarette smoking is associated with a 30–40% decrease in the risk of pre-eclampsia

(Conde-Agudela and Belizan, 2000). However, this benefit is cancelled out by the

substantial negative effects of smoking on fetal growth, risk for placental abruption, and

general health. Understanding the mechanisms of the preventive effects of smoking on preeclampsia could help to unravel important aspects of its pathophysiology.

Reducing risks related to paternity

While findings from studies on sperm exposure and paternity suggest an association

between length of exposure to sperm and the man’s history of fathering a pre-eclamptic

pregnancy, it is difficult to recommend preventive interventions for these two risk factors.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

21

However, health-care providers should realize that the antenatal care of a multiparous

patient with a new partner should be the same as in a woman presenting with her first

pregnancy, at least as far as the risk for pre-eclampsia is concerned (Robillard et al, 1999;

Roberts et al, 2001)

Use of low-dose aspirin to prevent pre-eclampsia

The use of low-dose aspirin during pregnancy decreases the risk of pre-eclampsia for

women considered at increased risk (Vogel et al, 2009), and also decreases rates of preterm birth, perinatal death, and incidence of small-for-gestational age infants (Gauer and

Atlas, 2008). There is no evidence of harm from low-dose aspirin therapy—including

placental abruption, antenatal admissions, fetal intraventricular hemorrhage and other

neonatal bleeding complications, admission to neonatal care unit, induction of labor, or

caesarean delivery—regardless of the woman’s risk status (Coomaraswamy et al, 2003).

The aspirin dosage used in studies ranged from 50 mg/day to 150 mg/day. Villar et al

showed a greater effect among women treated with doses greater than 75 mg/day of

aspirin (Villar et al, 2004).

Calcium supplementation to prevent pre-eclampsia

In a Cochrane review (Hofmeyr et al, 2009), calcium supplementation was associated with

reduced hypertension and pre-eclampsia, particularly for those at high risk of the disease

and with a low baseline dietary calcium intake (for those with an adequate calcium intake

the difference was not significant). No side effects of calcium supplementation were

recorded in the trials reviewed.

The data lend support to calcium supplementation for women at high risk of pre-eclampsia

and in communities with low dietary calcium intake. The absence of convincing evidence of

effectiveness from the largest trial (n=4589), which recorded no reduction in the rate or

severity of pre-eclampsia or in the timing of onset, have discouraged the use of calcium

supplementation in high resource countries.

Diet and exercise

Providers frequently advise women to make a range of changes to their diet and lifestyle to

reduce their risk of developing pre-eclampsia. The following interventions have been

evaluated in randomized trials: (1) aerobic exercise (Kramer, 2003), (2) protein

restriction(Kramer, 2003), (3) protein supplementation (Kramer, 2003), and (4) increasing

or decreasing salt intake (Duley et al, 2003). Because the studies were small, there is

insufficient evidence to either recommend or counsel against their use.

Other dietary supplements to prevent pre-eclampsia

Prophylactic magnesium (Sibai et al, 2005; Makrides and Crowther, 2003) and zinc

(Mahomed, 2003) supplementation have not been shown to be beneficial in preventing preeclampsia. Three randomized trials of fish oil supplementation for women at high risk for

pre-eclampsia revealed no reduction in the incidence of pre-eclampsia (Makrides et al,

2003). A recent study showing the benefits of vitamins C and E to prevent pre-eclampsia

was encouraging but needs further confirmation (Conde-Agudela and Belizan, 2000).

Secondary prevention (screening and detection)

Secondary prevention activities are aimed at early disease detection, thereby increasing

opportunities for interventions to prevent progression of pre-eclampsia. The ability to

prevent eclampsia is limited by lack of knowledge of its underlying cause. Prevention has

focused on identifying women with elevated blood pressure and/or proteinuria, followed by

close clinical and laboratory monitoring to recognize disease progression. Although these

22

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

measures do not prevent pre-eclampsia, they may be helpful in preventing some adverse

maternal and fetal sequelae associated with symptoms and in preventing progression to

eclampsia.

Focused antenatal care

Focused antenatal care is the most important part of secondary and tertiary prevention. The

decrease in maternal mortality and serious morbidity results mainly from the screening

(checking BP and testing urine for protein) and tertiary prevention (such as timed delivery)

associated with organized antenatal care. In order for antenatal care to be effective,

however, health care providers must be adequately trained to identify, prevent, and

manage pre-eclampsia and should have all of the essential equipment (in particular

accurate sphygmomanometers and means to detect protein in the urine), commodities, and

consumables (in particular for testing urine). In addition, adequate systems must be in

place to stabilize the woman and transfer her to the appropriate level of care.

Women, families, and communities need to understand danger signs and the importance of

seeking early and regular antenatal care. During antenatal care, health care providers can

assist women and their families to develop a birth preparedness and complication readiness

plan that will ensure that women access care in a timely manner.

Tertiary prevention (management of severe pre-eclampsia

and eclampsia)

Tertiary prevention focuses on the prevention of complications in women with preeclampsia. Reduction of maternal and fetal/newborn mortality and serious morbidity

depends on timely diagnosis and early referral. The three major interventions for

management of severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia are: anti-convulsant therapy, antihypertensive treatment, and timed delivery of the baby.

Anti-convulsant medications

Anticonvulsant drugs are used in the management of severe pre-eclampsia to prevent the

occurrence of eclamptic fits. Trials have compared magnesium sulfate with phenytoin,

nimodipine, and diazepam for prevention of eclampsia in women with pre-eclampsia. These

studies all support magnesium sulfate as the anticonvulsant of choice for women with preeclampsia (Duley, Gulmezoglu and Henderson-Smart, 2003).

Anticonvulsant drugs are used in the management of eclampsia to control and prevent the

recurrence of eclamptic fits. Magnesium sulfate has been compared with diazepam,

phenytoin, and lytic cocktail in randomized trials.

Magnesium sulfate vs. diazepam (Duley and Henderson-Smart, 2003):

When compared to diazepam, magnesium sulfate was associated with a reduction in

the risk of maternal death and in the risk of recurrence of convulsions.

When compared to diazepam, magnesium sulfate was associated with a reduction in

the risk of an Apgar score <7 at 5 min and in length of stay in a special care baby

unit (SCBU) >7 days.

Magnesium sulfate vs. phenytoin (Duley and Henderson-Smart, 2003):

Magnesium sulfate was associated with a reduction in the relative risk of recurrent

convulsions, the risk of pneumonia, the need for ventilation, and admission to an

intensive care unit

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

23

Babies whose mothers were allocated magnesium sulphate, rather than phenytoin,

had fewer admissions to a special care baby unit and fewer died or were in SCBU for

>7 days.

Magnesium sulfate vs. lytic cocktail (usually a mixture of chlorpromazine, promethazine

and pethidine) (Duley and Gulmezoglu, 2003):

Magnesium sulfate was substantially better at preventing further fits than lytic

cocktail and there was also a non-significant trend to fewer maternal deaths with

magnesium sulfate rather than lytic cocktail.

There was also a non-significant trend to fewer baby deaths (stillbirths and neonatal

deaths) in babies whose mothers were allocated magnesium sulfate, rather than lytic

cocktail.

Magnesium sulfate reduces the risk of eclampsia (Magpie Trail Collaborative Group, 2002)

without any substantive effect on longer-term morbidity and mortality for the women or

children (Magpie Trail Collaborative Group, 2007). Data from the Magpie (magnesium

sulfate for prevention of eclampsia) Trial (Smyth et al, 2009) provide reassurance about the

longer-term safety of magnesium sulfate when used for women with pre-eclampsia. There

appears to be no substantive effect on women's subsequent fertility, or their use of health

care services in the two years after the birth. Data from the main Magpie Trial follow up

study demonstrated that magnesium sulfate has no clear effect on the child's risk of severe

neuro-developmental delay (Magpie Trail Collaborative Group, 2007).

For prevention of occurrence and recurrence of eclamptic convulsions/fits in women with

severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, magnesium sulfate is more effective and has

fewer risks than diazepam, phenytoin, and lytic cocktail.

Do NOT give lytic cocktail, phenobarbital, or phenytoin

(Dilantin) to pregnant women.

Anti-hypertensive medications

An important objective in the care of a woman with severe hypertension, with or without

proteinuria, is to reduce blood pressure in order to avoid hypertensive encephalopathy and

cerebral hemorrhage. For this reason, the aim in treating severely hypertensive women is to

keep the blood pressure below dangerous levels (dBP<110 mmHg). It remains unclear

whether antihypertensive drug therapy for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy

is worthwhile (Duley, 2003).

While the goal of treatment of hypertension in pregnancy is to reduce maternal risk, careful

attention must be made not to harm the fetus. Antihypertensive medications may permit

prolongation of the pregnancy and thereby improve fetal maturity, but administration of a

powerful vasodilator will result in a decreased intervillous blood flow. Acute falls in maternal

systemic blood pressure may thus result in fetal compromise.

If antihypertensive treatment is required, there is no clear choice of drugs (Duley, 2003;

Cnossen et al, 2008). In general, however: (1) labetolol, nifedipine, and hydralazine are the

anti-hypertensive medications most commonly recommended for management of

hypertensive disorders in pregnancy; and (2) Diuretics (furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide)

and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (captopril) are contraindicated for use as antihypertensive agents during pregnancy. Refer to Table XX for a broad overview of

advantages and disadvantages of anti-hypertensive medications that may be used for

management of pre-eclampsia/eclampsia (Cnossen et al, 2008; National High Blood

Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy, 2001).

24

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Table xx. Advantages and disadvantages of selected anti-hypertensives for use during

pregnancy

Medication

Calcium channel

blockers (nifedipine)

Combined alpha and

beta-blocker

(labetalol

hydrochloride)

Advantages

A multicenter prospective cohort

study of first-trimester drug

exposures reported no increase

in major teratogenicity from

these agents

Causes dilatation of small

arteries

None of these agents has been

associated with any consistent ill

effects

Less likely to reduce uteroplacental perfusion than betablockers and may improve

cerebral circulation

Available data suggest that the

antihypertensive effect is not

associated with compromised

renal or uterine blood flow

Disadvantages

Experience with calcium antagonists is

limited

Safety record of labetalol in pregnancy

is not as well established as that of

methyldopa

Direct acting

vasodilator

(hydralazine)

Smooth muscle relaxant,

causing vasodilatation

Associated with more maternal and

perinatal adverse effects than other

drugs*

Alpha-Adrenergic

Agonist

(methyldopa)

Stable uteroplacental blood flow

and fetal hemodynamics

No long-term adverse effects on

development among children

exposed to methyldopa in utero

Causes somnolence in many individuals

β -blockers

(atenolol)

None of these agents has been

associated with any consistent ill

effects

β blockers prescribed during early

pregnancy, specifically atenolol, may be

associated with growth restriction

Long-term follow-up studies are lacking

Diuretics

(furosemide,

hydrochlorothiazide)

Reduce blood pressure

Reduce maternal plasma volume and

can cause electrolyte disturbances

Angiotensinconverting enzyme

inhibitors (captopril)

May be safe in early pregnancy

but women taking these agents

should be warned about the

possible risks of this class of

drugs in pregnancy and advised

to discontinue

Administration during the second and

third trimesters can result in a number

of fetal adverse effects, including

growth retardation, renal failure,

persistent patent ductus arteriosus,

respiratory distress syndrome, fetal

hypotensive syndrome, and prepartum

death

Induction of labor

Apart from Cesarean operation or induction of labor (and therefore delivery of the placenta),

there is no known cure for pre-eclampsia. A decision to induce labor will need to weigh

benefits and risks for both the woman and fetus. The National High Blood Pressure

* Recent data on maternal and perinatal adverse effects associated with hydralazine have led some

researchers to state that hydralazine should no longer be considered the anti-hypertensive medication

of choice (Smyth et al, 2009).

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

25

Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy recommends the

following when considering delivering the baby to manage gestational hypertension:

“First, any therapy for pre-eclampsia other than delivery must have as its

successful end point the reduction of perinatal morbidity and mortality.

Second, the cornerstone of obstetric management of pre-eclampsia is based on

whether the fetus is more likely to survive without significant neonatal complications

in utero or in the nursery” (National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working

Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy, 2001).

The decision to terminate pregnancy will depend upon:

1. Severity of the disease

2. Gestational age

3. Maternal and fetal condition

The WHO (WHO, 2003) recommends the following for timing of delivery:

In severe pre-eclampsia, delivery should occur within 24 hours of the onset of

symptoms.

In eclampsia, delivery should occur within 12 hours of the onset of convulsions/fits.

When the gestational hypertension is mild, induction of labor is associated with improved

maternal outcome and should be advised for women beyond 37 weeks’ gestation

(Koopmans et al, 2009).

26

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Overview of interventions to prevent pre-eclampsia and

eclampsia

For an overview of preventive interventions, see Table XX.

Table xx. Overview of interventions to prevent pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Prevention

Intervention

Pregnancy outcome

Prevention of IUGR

Theoretically contributes to

primary prevention of preeclampsia (and IUGR) in the

next generation

Recommended

Family planning

Potential to reduce

pregnancies at risk for preeclampsia

Recommended

Pre-conceptual

prevention and/or

treatment of obesity

Potential to reduce preeclampsia

Recommended

Smoking

Reduces risk of preeclampsia

Not recommended

Low-dose aspirin

Reduces pre-eclampsia

Reduces fetal or neonatal

deaths

Advise women with more

than one moderate risk

factor for pre-eclampsia to

take 75 mg of aspirin daily

from 12 weeks gestation

until the birth of the baby.

Calcium

supplementation

Reduces pre-eclampsia in

those at high risk and with

low baseline dietary calcium

intake

No effect on perinatal

outcome

Primary

Magnesium or zinc

supplementation

Fish oil

supplementation and

other sources of

fatty acids

Heparin or lowmolecular weight

heparin

Anti-oxidant vitamins

(C, E)

Secondary

Recommendation

BP and urinary

protein screening

during antenatal and

postnatal visits

No reduction in preeclampsia

Advise women at risk of

gestational hypertension

living in communities with

low dietary calcium intake,

to take 1 G of calcium daily

from 12 weeks gestation

until the birth of the baby.

Insufficient evidence to

recommend*

No effect on low- or high-risk

populations

Insufficient evidence to

recommend*

Reduces pre-eclampsia in

women with renal disease

and thrombophilia

Reduced pre-eclampsia in

one trial

No reduction in preeclampsia

Reduces some adverse

maternal and fetal sequelae

Assists in preventing

progression to eclampsia

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Insufficient evidence to

recommend*

Insufficient evidence to

recommend*

Recommend for all pregnant

women

27

Prevention

Intervention

Protein or salt

restriction

Anti-convulsive drugs

Magnesium

sulfate

Diazepam

Tertiary

Anti-hypertensive

drugs

Induction of labor

Pregnancy outcome

No reduction in preeclampsia

Recommendation

Insufficient evidence to

recommend*

Reduces the risk of

eclampsia without any

substantive effect on longerterm morbidity and mortality

for the women or children

Recommend for women with

severe pre-eclampsia and

eclampsia

When compared to

diazepam, magnesium

sulfate was associated with a

reduction in the risk of

maternal death and in the

risk of recurrence of

convulsions.

When compared to

diazepam, magnesium

sulfate was associated with a

reduction in the risk of an

Apgar score <7 at 5 min and

in length of stay in a special

care baby unit (SCBU) >7

days.

Improves maternal outcome.

May permit prolongation of

the pregnancy and thereby

improve fetal maturity.

Acute falls in maternal

systemic blood pressure can

result in fetal compromise.

Improves maternal and fetal

outcome when carried out

according to

recommendations for severe

pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Recommend if magnesium

sulfate is not available

Recommend if diastolic BP

110 mm Hg or more

Consider for women beyond

37 weeks’ gestation with

mild pre-eclampsia.

Recommend based on

severity of the disease,

gestational age, and

maternal and fetal condition

* Insufficient evidence=small trials or inconclusive results

28

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

Reference manual

Management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Management protocols are copied from: WHO. MCPC. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

Introduction

In order to detect early signs of pregnancy-induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia, regular

antenatal visits are necessary, especially in the third trimester of pregnancy. At each

antenatal visit, the woman’s blood pressure must be measured and her urine should be

checked for protein from 20 weeks gestation and/or if diastolic blood pressure is more than

90 mmHg. Pregnant women should be encouraged to come for antenatal care early in their

pregnancy so that a baseline value for their blood pressure can be obtained.

Survival and positive outcomes for the woman and her baby depend on timely diagnosis and

timely treatment at the appropriate level of care. In general:

Women with gestational hypertension whose diastolic BP is less than 90 mmHg can

be managed at an outpatient clinic with basic emergency obstetric care facilities

Women with mild pre-eclampsia (<37 weeks gestation) can be managed at an

outpatient clinic with basic emergency obstetric care facilities

Women with mild pre-eclampsia (>37 weeks gestation) should be managed at a

facility with comprehensive emergency obstetric care facilities

Women with severe pre-eclampsia should be managed at a facility with

comprehensive emergency obstetric care facilities

Women with eclampsia should be managed at a facility with comprehensive

emergency obstetric care facilities

If there is a rise in blood pressure, the woman should be closely monitored at frequent

intervals. If proteinuria develops, she should receive care in a health facility capable of

coping with a woman who may develop severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia.

Gestational hypertension

Diagnostic criteria

Two readings of diastolic BP 90 mm Hg or more but below 110 mm Hg 4 hours apart after

20 weeks gestation

No proteinuria

Management

The woman is usually managed as an outpatient and followed up weekly at home or at a

local clinic. Management on an outpatient basis at each visit:

Monitor blood pressure, urine (for proteinuria) and fetal condition (growth, movement,

heart rate) weekly

Check if the woman has severe headache, visual disturbances or abdominal pain

Counsel the woman and her family about the danger signals of severe pre-eclampsia,

ensuring that they know the importance of obtaining immediate medical help if any of the

signs develop.

Prevention and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Version 7.0 / 10 January 2011

29

If the blood pressure decreases to normal levels and there are no other complications, the

condition has stabilized and the woman should be allowed to proceed with normal labour

and childbirth.

Refer for care at a health care facility capable of coping with a woman who may develop

severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia if:

o

the blood pressure rises

o

proteinuria develops

o

there is significant fetal growth restriction (signs of poor fetal growth)

o

there is evidence of fetal compromise (abnormal fetal movements, heart rate,

or growth)

Mild pre-eclampsia - Gestation less than 37 weeks

Diagnostic criteria

Two readings of diastolic BP 90 mm Hg or more but below 110 mm Hg 4 hours apart after

20 weeks gestation

Proteinuria up to 2+

Management

If signs remain unchanged or normalize, follow up twice a week as an outpatient:

Monitor blood pressure, urine (for proteinuria), reflexes and fetal condition.

Counsel the woman and her family about danger signals of severe pre-eclampsia or

eclampsia.

Encourage additional periods of rest.

Encourage the woman to eat a normal diet (salt restriction should be discouraged).

Do not give anticonvulsants, anti-hypertensives, sedatives or tranquillizers.