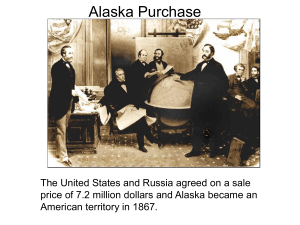

“I Took Panama and let Congress debate it later

advertisement

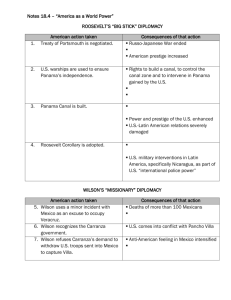

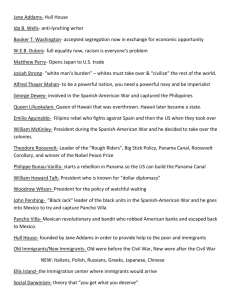

“I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Analyze the following primary source and identify the information it provides regarding the question: What role did the United States play in the Panamanian Revolution and is President Roosevelt’s autobiography accurate? Answer the specific question provided and be prepared to present the information to your classmates. From a letter by Jose Marroquin, President of Colombia Written in protest of the presence of United States Navy and Marines in Panama at the outset of the Panamanian Revolution. Marroquin supported the Hay-Herran Treaty but felt mistreated by the United States after the revolution as worried that the loss of Panama might lead to his loss of power in Columbia. The Rights of Colombia- A Protest and Appeal (November 28, 1903) “The Government of the United States is treating Colombia in a manner that seems dishonorable to all the people of that country. American Secretary of State Hay has astonished the world by finding a right to exclude the troops of Colombia from the Isthmus of Panama. The United States violated international law by recognizing the independence of Panama only days after the revolution and before the nation of Colombia had a chance to put down the insurrection. Colombia did not recognize the southern states which seceded during the American Civil War- why should the United States recognize the seceding states of Panama? How are you to escape the condemnation of history? Never has any nation dealt with a weak one in a way that seemed dishonorable to any considerable part of its own people but that history has affirmed the judgment of the protesting minority.” “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Source The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of BunauVarilla Type of Source The interview was given to an investigative journalist 37 years after the events. Bunau-Varilla was almost 90 years old at the time of the interview. This was a private letter (not Private intended for public Letter to Hay consumption) between the former President and his former Secretary of State. The letter was written in 1912, after Roosevelt failed in his bid to win the presidency as a Progressive. Written after Roosevelt’s death What does I by former French engineer and took Panama first Panamanian Minister to Mean America. Written as a personal narrative of what happened in Panama, and was the second book written by Bunau-Varilla about the Panamanian Revolution. Published in the New York “The Man Times investigative story on the Behind the events in Panama Egg”: Muckraking attempt to Cartoon investigate the president. Letter by Jose Marroquin “Panama or Bust” Cartoon Written in protest of the presence of United States Navy and Marines in Panama at the outset of the Panamanian Revolution. Marroquin supported the Hay-Herran Treaty but felt mistreated by the United States after the revolution as worried that the loss of Panama might lead to his loss of power in Columbia. The New York Times was developed to counter the yellow journalism of other New York newspapers. The paper was not supportive of American imperial efforts. Information Support/Challenge “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Analyze the following primary source and identify the information it provides regarding the question: What role did the United States play in the Panamanian Revolution and is President Roosevelt’s autobiography accurate? Answer the specific question provided and be prepared to present the information to your classmates. The Man Who Invented Panama, By ERIC SEVAREID The interview was given to an investigative journalist 37 years after the events. BunauVarilla was almost 90 years old at the time of the interview. It was his [Buna-Varillia’s] memories that interested me that winter in Paris. A cable from CBS in New York requested me to find out if the Colonel was still alive and if so, to have him make a fiveminute broadcast on the Robert Ripley “Believe It or Not” radio program about his role in the Panama Canal. Very much alive in a magnificent apartment…the old gentleman immediately agreed. Clearly, it was an immense pleasure for him to be resurrected on the American scene, if only for five short minutes on the radio. He had his vanity, and he was entitled to it. [He told me during the interview that] The French company [trying to build a canal] failed in 1889, and nearly everyone involved gave up—except Bunau-Varilla. He wrote some twenty books. He travelled all over the world trying to find private backing for a resumption of the effort. He had Czarist Russia committed, as a partner with France, when the French government collapsed and…England was too busy with the Boer War. The United States was his only hope… …The Isthmus [Panama] was then part of Colombia, and Colombia changed her mind about ceding a right of way. Under Bunau-Varilla’s pressure, Colombia changed her mind back again, and a treaty was signed. More trouble: the Colombian senate in August of 1903 refused to ratify the treaty, even under private warnings, chiefly from the Frenchman, that the Panamanians might simply secede from Colombia. The legislature would not bow to threats. There was only one play Bunau-Varilla had left in his bag of tricks—to carry out the threats. So he applied himself to fomenting Panama’s revolution. First he had to be sure that if the revolt came off successfully, the United States would give her protection to the new nation. In his autobiography, Bunau-Varilla says that he discovered from friends of President Theodore Roosevelt that the U.S. would do so. But to me, as I sat one day in the old Colonel’s apartment, he told this story, as closely as my memory retains it: I called on Mr. Roosevelt [at the White House] and asked him point blank if, when the revolt broke out, an American war ship would be sent to Panama to “protect American lives and interests.” The President just looked at me; he said nothing. Of course, a President of the United States could not give such a commitment, especially to a foreigner and private citizen like me. But his look was enough for me. I took the gamble. “He is a very able fellow,” Roosevelt later wrote about the encounter, “and it was his business to find out what he thought our Government would do. I have no doubts that he was able to make a very accurate guess, and to advise his people accordingly. In fact, he would have been a very dull man if he had been unable to make such a guess.” Not that a single man can produce a rebellion; there were plenty of disgruntled Panamanians ready to help, and various meetings with their representatives took place at Bunau-Varilla’s WaldorfAstoria suite. They wanted six million dollars, chiefly to pay their ragged guerrilla force. BunauVarilla got the price down, he said, to 1100,000, and paid it out of his own pocket. Next he busied himself drafting a Panamanian declaration of independence and a constitution. He even bought silk at Macy’s for a Panamanian flag, which he designed and which his wife and a family friend stitched together at a Westchester County estate. “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Source The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of BunauVarilla Type of Source The interview was given to an investigative journalist 37 years after the events. Bunau-Varilla was almost 90 years old at the time of the interview. This was a private letter (not Private intended for public Letter to Hay consumption) between the former President and his former Secretary of State. The letter was written in 1912, after Roosevelt failed in his bid to win the presidency as a Progressive. Written after Roosevelt’s death What does I by former French engineer and took Panama first Panamanian Minister to Mean America. Written as a personal narrative of what happened in Panama, and was the second book written by Bunau-Varilla about the Panamanian Revolution. Published in the New York “The Man Times investigative story on the Behind the events in Panama Egg”: Muckraking attempt to Cartoon investigate the president. Letter by Jose Marroquin “Panama or Bust” Cartoon Written in protest of the presence of United States Navy and Marines in Panama at the outset of the Panamanian Revolution. Marroquin supported the Hay-Herran Treaty but felt mistreated by the United States after the revolution as worried that the loss of Panama might lead to his loss of power in Columbia. The New York Times worked to counter the yellow journalism of other New York newspapers. The paper was not supportive of American imperial efforts. Information Support/Challenge “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Analyze the following primary source and identify the information it provides regarding the question: What role did the United States play in the Panamanian Revolution and is President Roosevelt’s autobiography accurate? Answer the specific question provided and be prepared to present the information to your classmates. The New York Times was developed to counter the yellow journalism of other New York newspapers. The paper was not supportive of American imperial efforts. “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Source The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of BunauVarilla Type of Source The interview was given to an investigative journalist 37 years after the events. Bunau-Varilla was almost 90 years old at the time of the interview. This was a private letter (not Private intended for public Letter to Hay consumption) between the former President and his former Secretary of State. The letter was written in 1912, after Roosevelt failed in his bid to win the presidency as a Progressive. Written after Roosevelt’s death What does I by former French engineer and took Panama first Panamanian Minister to Mean America. Written as a personal narrative of what happened in Panama, and was the second book written by Bunau-Varilla about the Panamanian Revolution. Published in the New York “The Man Times investigative story on the Behind the events in Panama Egg”: Muckraking attempt to Cartoon investigate the president. Letter by Jose Marroquin “Panama or Bust” Cartoon Written in protest of the presence of United States Navy and Marines in Panama at the outset of the Panamanian Revolution. Marroquin supported the Hay-Herran Treaty but felt mistreated by the United States after the revolution as worried that the loss of Panama might lead to his loss of power in Columbia. The New York Times was developed to counter the yellow journalism of other New York newspapers. The paper was not supportive of American imperial efforts. Information Support/Challenge “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Analyze the following primary source and identify the information it provides regarding the question: What role did the United States play in the Panamanian Revolution and is President Roosevelt’s autobiography accurate? Answer the specific question provided and be prepared to present the information to your classmates. Published in the New York Times investigative story on the events in Panama. The cartoon was a muckraking attempt to investigate the president. “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Source The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of BunauVarilla Type of Source The interview was given to an investigative journalist 37 years after the events. Bunau-Varilla was almost 90 years old at the time of the interview. This was a private letter (not Private intended for public Letter to Hay consumption) between the former President and his former Secretary of State. The letter was written in 1912, after Roosevelt failed in his bid to win the presidency as a Progressive. Written after Roosevelt’s death What does I by former French engineer and took Panama first Panamanian Minister to Mean America. Written as a personal narrative of what happened in Panama, and was the second book written by Bunau-Varilla about the Panamanian Revolution. Published in the New York “The Man Times investigative story on the Behind the events in Panama Egg”: Muckraking attempt to Cartoon investigate the president. Letter by Jose Marroquin “Panama or Bust” Cartoon Written in protest of the presence of United States Navy and Marines in Panama at the outset of the Panamanian Revolution. Marroquin supported the Hay-Herran Treaty but felt mistreated by the United States after the revolution as worried that the loss of Panama might lead to his loss of power in Columbia. The New York Times was developed to counter the yellow journalism of other New York newspapers. The paper was not supportive of American imperial efforts. Information Support/Challenge “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Analyze the following primary source and identify the information it provides regarding the question: What role did the United States play in the Panamanian Revolution and is President Roosevelt’s autobiography accurate? Answer the specific question provided and be prepared to present the information to your classmates. Private letter from President Roosevelt to his former Secretary of State, John Hay This was a private letter (not intended for public consumption) between the former President and his former Secretary of State. The letter was written in 1912, after Roosevelt failed in his bid to win the presidency as a Progressive. July 2, 1915 To talk of Columbia as a responsible power to be dealt with as we would deal with Holland or Belgium or Switzerland or Denmark is a mere absurdity. The analogy is with a group of Sicilian or Calabrian bandits…You could no more make an agreement with the Columbian rulers than you could nail currant jelly to a wall…I did my best to get them to act straight. Then I determined that I would do what ought to be done without regard to them. The people of Panama were a unit in desiring the canal and wishing to overthrow the rule of Columbia. If they had not revolted, I should have recommended to Congress to take possession of the Isthmus by force of arms; and, as you will see, I had actually written the first draft of my message to this effect. When they [Columbians living in Panama] revolted, I promptly used the Navy to prevent bandits, who had tried to hold us up, from spending months of futile bloodshed in conquering or endeavoring to conquer the isthmus, to the lasting damage of the Isthmus, of us, and of the world. I did not consult [Secretary of State] Hay or [Secretary of War] Root, or anyone else as to what I did, because a council of war does not fight; and I intended to do the job once and for all. “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Source The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of BunauVarilla Type of Source The interview was given to an investigative journalist 37 years after the events. Bunau-Varilla was almost 90 years old at the time of the interview. This was a private letter (not Private intended for public Letter to Hay consumption) between the former President and his former Secretary of State. The letter was written in 1912, after Roosevelt failed in his bid to win the presidency as a Progressive. Written after Roosevelt’s death What does I by former French engineer and took Panama first Panamanian Minister to Mean America. Written as a personal narrative of what happened in Panama, and was the second book written by Bunau-Varilla about the Panamanian Revolution. Published in the New York “The Man Times investigative story on the Behind the events in Panama Egg”: Muckraking attempt to Cartoon investigate the president. Letter by Jose Marroquin “Panama or Bust” Cartoon Written in protest of the presence of United States Navy and Marines in Panama at the outset of the Panamanian Revolution. Marroquin supported the Hay-Herran Treaty but felt mistreated by the United States after the revolution as worried that the loss of Panama might lead to his loss of power in Columbia. The New York Times was developed to counter the yellow journalism of other New York newspapers. The paper was not supportive of American imperial efforts. Information Support/Challenge “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Analyze the following primary source and identify the information it provides regarding the question: What role did the United States play in the Panamanian Revolution and is President Roosevelt’s autobiography accurate? Answer the specific question provided and be prepared to present the information to your classmates. WHAT DOES "I TOOK PANAMA" MEAN? Written after Roosevelt’s death by the former French engineer and first Panamanian Minister to America. Written as a personal narrative of what happened in Panama, and was the second book written by Bunau-Varilla about the Panamanian Revolution. The only straw at which their drowning calumny could clutch was the celebrated phrase: "I took Panama," which Theodore Roosevelt pronounced in California. When the sentence was reported by the papers I understood that it meant: "I took Panama because Panama offered herself in order to be protected against Colombia's tyranny and greed." Recently in speaking to a distinguished visitor to Oyster Bay---William Morton Fullerton, the eminent writer on international problems---Theodore Roosevelt explained the sentence in this familiar way: "I took Panama because Bunau-Varilla brought it to me on a silver platter." It is obvious that Theodore Roosevelt's own interpretation of his sentence harmonizes entirely with mine. It does not mean as the advocates of Colombia say: "I took Panama away from her mother country Colombia because the interests of the United States wanted it." It means: "I protected Panama, at her pressing request, from the tyrannical greed of Colombia, because her preservation and the world's interests wanted it." Philippe Bunau-Varilla. The Great Adventure of Panama: Wherein Are Exposed Its Relation to the Great War and also the Luminous Traces of The German Conspiracies Against France and the United States. Doubleday, Page & Company: Garden City, New York, 1920. “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Source The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of BunauVarilla Type of Source The interview was given to an investigative journalist 37 years after the events. Bunau-Varilla was almost 90 years old at the time of the interview. This was a private letter (not Private intended for public Letter to Hay consumption) between the former President and his former Secretary of State. The letter was written in 1912, after Roosevelt failed in his bid to win the presidency as a Progressive. Written after Roosevelt’s death What does I by former French engineer and took Panama first Panamanian Minister to Mean America. Written as a personal narrative of what happened in Panama, and was the second book written by Bunau-Varilla about the Panamanian Revolution. Published in the New York “The Man Times investigative story on the Behind the events in Panama Egg”: Muckraking attempt to Cartoon investigate the president. Letter by Jose Marroquin “Panama or Bust” Cartoon Written in protest of the presence of United States Navy and Marines in Panama at the outset of the Panamanian Revolution. Marroquin supported the Hay-Herran Treaty but felt mistreated by the United States after the revolution as worried that the loss of Panama might lead to his loss of power in Columbia. The New York Times was developed to counter the yellow journalism of other New York newspapers. The paper was not supportive of American imperial efforts. Information Support/Challenge “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Review the background on America’s interest in the Panama Canal and highlight important people and events. Then read the following excerpt from President Theodore Roosevelt’s autobiography. On the left hand side summarize the argument presented in each section of the writing. After summarizing, list all of the explanations Roosevelt provides to justify his actions in Panama. Pay particular attention to the adjectives he uses to describe his actions, the reaction of the Panamanians, and the benefits of his actions. Background: American desire for an isthmian canal had its impetus as far back as the 1840s migration to Oregon territory and the California Gold Rush of 1848. To protect the potential economic and strategic boon of a canal in 1850 the United States signed a treaty with Great Britain, the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, where both nations agreed to seek independent rights to a canal. After the American Civil War the craving for the monetary benefits of a quicker route from the east coast to the west coast of the United States drove President Ulysses S. Grant to appoint a commission to research the best potential location for a canal between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Although the Grant and McKinley administrations both found that a canal route through Nicaragua would be the most advantageous, a French company began in 1878 to construct an inter-ocean canal in the Panamanian territory of the nation of Columbia. By 1898, the French effort to construct a canal, which cost over $300,000,000 and thousands of lives, was declared a failure and discontinued. At the same time American needs for a quicker route between coasts was exacerbated by the growing Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars. Secretary of the Navy, and soon to be President, Theodore Roosevelt immediately saw the strategic importance of constructing and controlling a canal. Buoyed by the Hay-Poncefote Treaty of 1901 in which the British relinquished their claim to a canal, Roosevelt began an intensive search for territory to build a canal. As Roosevelt and the American government made the canal a priority, a former member of the French construction team in the Panamanian territory of Columbia, Philippe Bunau-Varillia, sought to contract with someone to continue the construction of a canal. Working from New York City, Bunau-Varilla prepared maps and budgets to use while lobbying the United States Congress and President Roosevelt to sell the territory of Panama as the logical location for a transoceanic canal. As the United States Senate debated the possible locations for the canal, Bunau-Varillia implemented one of his most effective tactics when he mailed a letter containing a one cent Nicaraguan stamp depicting the eruption of volcano Mt. Momotombo. Given the choice between active volcanoes in Nicaragua and the geologically safer Panama, the Senate agreed in 1902 to support a Panamanian route. By 1903, Bunau-Varilla’s efforts led to a change of administrative policy favoring a Panamanian canal and the negotiation of the American assumption of French debts and territory. The result of the American change of policy was embodied in the Hay-Herran Treaty signed with the President of Columbia, Jose Marroquin. The treaty, approved by the United States Senate but not by its Columbian counterpart, promised the lease of strip of land 10 miles wide for 100 years at the purchase price of $40 million and a $250,000 year annuity. Despite President Marroquin’s signature on the treaty the Columbian Parliament’s refusal to ratify the treaty set in motion a series of events that have been interpreted differently by many historians. Here is President Roosevelt’s interpretation of the events. “The people of Panama were delighted with the treaty (Hay-Herran Treaty), and the President of Columbia, who embodied in his own person the entire government of Colombia, had authorized they would seize the French Company at the end of another year and take for themselves the treaty to be made. But after the treaty had been made the Columbian government thought it had the matter in its own hands; and the further thought, equally wicked and foolish, came into the heads of the people in control at Bogota that the forty million dollars which the United States had agreed to pay the Panama Canal Company… President Maroquin…had agreed to the Hay-Herran Treaty…he had the absolute power of an unconstitutional dictator to keep his promises or break it. He determined to break it. To furnish him an excuse for breaking it he devised the plan of summoning a Congress especially called to reject the canal treaty. This Congress—a Congress of mere puppets—did, without a dissenting vote…the fact that this was a mere sham, and that the President had entire power to confirm his own treaty and act on it if he desired, was shown as soon as the revolution took place…When the president stated that “If the government of the United States would land troops and restore the Colombian sovereignty” the Colombian president would “declare martial law; and by virtue of vested constitutional authority,” would approve by decree the ratification of the canal treaty assigned…This of course, is proof positive that the Colombian dictator had used his Congress as a mere shield… … By my direction, Secretary Hay…repeatedly warned Columbia that grave consequences might follow her rejection of the treaty. The possibility of ratification did not wholly pass away until the close of the session of the Colombian Congress on the last day of October. There would then be two possibilities. One was that Panama would remain quiet. In that case I was prepared to recommend to Congress that we should at once occupy the Isthmus anyhow, and proceed to dig the canal; and I had drawn out a draft of my message to this effect. But from the information I received, I deemed it likely that there would be a revolution in Panama as soon as the Colombian Congress adjourned without ratifying the treaty, for the entire population of Panama felt that the immediate building of the canal was of vital concern to their well being. Correspondents of the different newspapers on the Isthmus had sent to their respective papers widely published forecasts indicating that there would be a revolution in such event. …Two army officers who had returned from the Isthmus, saw me and told me that there would unquestionably be a revolution on the Isthmus, that the people were unanimous in their disgust over the failure of the government to ratify the treaty…accordingly I directed the Navy Department to station various ships within easy reach of the Isthmus to be ready to act in event of need arising…On November 3 the revolution occurred. Practically everybody on the Isthmus, including all the Colombian troops that were already stationed there, joined in the revolution, and there was no bloodshed. But on that same day four hundred new Colombian troops were landed at Colon. Fortunately, the gunboat Nashville…reached Colon almost immediately afterwards, and when the commander of the Colombian forces threatened the lives and property of the American citizens, including women and children, in Colon, Commander Hubbard landed a few score sailors and marines to protect them. By a mixture of firmness and tact he not only prevented any assault on our citizens, but persuaded the Colombian commander to reembark his troops for Cartagena. On the Pacific side a Colombian gunboat shelled the City of Panama… “No one connected with the American Government had any part in preparing, inciting, or encouraging the revolution, and except for the reports of our military and naval officers, which I forwarded to Congress, no one connected with the Government had any previous knowledge concerning the proposed revolution, except such as was accessible to any person who read the newspapers and kept abreast of current questions and current affairs. By the unanimous action of its people, and without the firing of a shot, the state of Panama declared themselves an independent republic. The time for hesitation on our part had passed. “My belief then was, and the events that have occurred since have more than justified it, that from the standpoint of the United States it was imperative, not only for civil but for military reasons, that there should be the immediate establishment of easy and speedy communication by sea between the Atlantic and the Pacific…” “Every consideration of international morality and expedience, of duty to the Panama people, and of satisfaction of our own national interests and honor, bade us take immediate action. I recognized Panama forthwith on behalf of the United States, and practically all the countries of the world immediately followed suit. The State Department immediately negotiated a canal treaty with the new Republic. One of the foremost men in securing the independence of Panama, and the treaty which authorized the United States forthwith to build the canal, was M. Philippe Bunau-Varilla, an eminent French engineer… “From the beginning to the end our course was straightforward and in absolute accord with the highest of standards of international morality. Criticism of it can come only from misinformation, or else from a sentimentality which represents both mental weakness and a moral twist. To have acted otherwise than I did would have been on my part betrayal of the interests of the United States, indifference to the interests of Panama, and to the interests of the world at large…I did not lift my finger to incite the revolutionists…I simply ceased to stamp out the different revolutionary fuses that were already burning…We gave to the people of Panama self-government, and freed them from subjection to alien oppressors. We did our best to get Colombia to let us treat her with a more than generous justice; we exercised patience to beyond the verge of proper forbearance…” Summarize Roosevelt’s Stance on His Involvement in Panama: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________