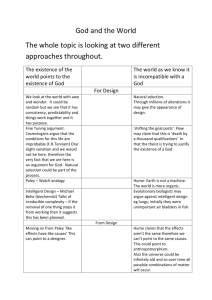

Microsoft Word - Argument from design Godx

advertisement

© Michael Lacewing The argument from design: God This handout follows the handouts on ‘The Argument from Design: Paley v. Hume’ and ‘Swinburne’s Argument from Design’. You should read those handouts first. The argument from design argues from the order and regularity that we see in the universe to the existence of a God that designed the universe. Paley, Hume and Swinburne all agree that even if we could infer the existence of a designer of the universe, it is an extra step to argue that the designer is God. Hume, Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, Pt 5 Hume understands the argument from design to be an argument from analogy: 1 2 3 4 In the organisation of parts for a purpose (‘the fitting of means to ends’), nature resembles the products of human design. Similar effects have similar causes. The cause of the products of human design is an intelligent mind that intended the design. Therefore, the cause of nature is an intelligent mind that intended the design. If we are arguing for a designer on the basis of a similarity between human inventions and the universe, then shouldn’t we think that the designer is more similar to human beings than God is traditionally said to be? Here are five objections based on this idea. 1 The scale and quality of the design reflect the power and ability of the designer (p. 24). The universe isn’t infinite. So we can’t infer that the designer is infinite. And we can’t tell whether the universe is perfect; perhaps it contains some mistakes in design. If so, we should say that the designer isn’t fully skilled, but made mistakes. So we can’t infer that the designer is perfect or infinite in power or knowledge. We also have no reason to think the designer is good (Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, §11, p. 73). By contrast, God is said to be omnipotent, omniscient and supremely good. So we can’t infer that the designer is God. 2 Designers are not always creators (p. 25). Someone who designs a car may not also build it. So we can’t infer that the designer of the universe also created the universe. The creator could just be following someone else’s designs. But God is said to be the creator of the universe; so we can’t infer that the designer is God. The design may have resulted from many small improvements made by many people (p. 25). So we cannot infer that ‘the designer’ is just one person. More generally, we can’t infer that the powers to design and create a universe are all united in one being, rather than being shared out between lots of different beings. But God is said to be one. We find mind always connected to body (p. 25). There is no reason to think that the designer has no body. But God is thought to be just a mind. 3 4 5 Designers can die even as their creations continue (p. 26). So the designer may have designed the universe and then died. God is said to exist eternally, so again, we can’t say the designer is God. In summary, the argument from design doesn’t show that the designer is omnipotent, omniscient, the creator of the universe, just one being, non-corporeal, or even still in existence. So it doesn’t show that God – as a single omnipotent, omniscient, eternal creator spirit – exists. Kant’s Critique Kant echoes Hume’s first two points (Critique of Pure Reason, Second Division (Transcendental Dialectic), Bk 2, Ch. 3, §6). The argument from design can only work by analogy, and so, on the basis of order in nature, we can at best infer that there is a designer of nature. We can’t draw any conclusions about the designer creating the universe or matter – just as human designers don’t literally create the matter they work with, but only shape it. Again, we can only say that this designer must be ‘very great’, though we don’t really understand how great and can’t form any ‘determinate’ ideas of this being. Swinburne, ‘The Argument from Design’, pp. 209–10; Paley, Natural Theology, Chs 24–6 Swinburne accepts Hume’s objection (1) – if the designer is God, many of God’s traditional qualities will need to be established by some other argument. Paley, by contrast, argues that the argument from design can establish that the designer has all the features of God (Ch. 24). He accepts that the argument shows only that the designer has the power and knowledge necessary to create this universe, but he says that such power and knowledge is ‘beyond comparison and there is no reason… to assign limits to it’ (p. 287). So, considered in terms of our ability to conceive of such power and knowledge, they are unlimited, and so infinite. ‘Infinite’ power is a ‘superlative’, like ‘best’ and ‘greatest’. We are expressing our conception of such power in the strongest terms we have. In Ch. 26, Paley adds that the designer is good. The design of nature benefits natural organisms and also gives rise to more pleasure than is strictly necessary for the design to work. Furthermore, where there is evil, we have no evidence to think that it is by design. However, to assess this last point would require us to discuss the problem of evil. In reply to (2) and (3), Swinburne invokes Ockham’s razor. Simplicity requires that we shouldn’t suppose that two possible causes exist when only one will do. If we can explain the design and creation of the universe by supposing that there is just one being capable of this, then we shouldn’t suppose that there is more than one being unless we have positive evidence that there is. Swinburne argues that the order in the universe that requires a designer is found in the laws of nature. So if, for instance, different parts of the universe operated according to different laws, then that could be evidence for more than one designer being involved. But, as Paley also argues (Ch. 25), the uniformity of nature gives us good reason to suppose that there is just one designer and creator. In reply to (4), the explanation requires that the designer doesn’t have a body. Having a body means that one has a particular location in space and can only act on a certain area of space. If God’s effects are the laws of nature, and these hold throughout the universe, then God can act everywhere in space simultaneously. So it is better to say that God has no body. In reply to (5), Swinburne asserts that the objection only works if we are thinking about things in spatial order, such as inventions. But temporal order – regularities in ‘what happens next’ – requires that the agent is acting at that time. To bring about order in what happens next, I must act. If I don’t act, then the laws of nature take over. But these laws of nature are exactly what we are explaining in terms of God’s activity. So God acts wherever the laws of nature hold. So God must continue to exist. Paley adds (Ch. 24) that this also establishes that God’s existence has no beginning or end. It has no beginning, because at such a time, there would have been nothing – and out of nothing, nothing can come into existence. So the designer, God, must always have existed. This does not establish that the designer, God, cannot – at some point in the future – cease to exist; but if we reflect on what kind of existence God must have in order to always have existed, then we have reason to think that God must continue to exist always as well.