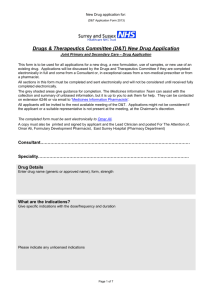

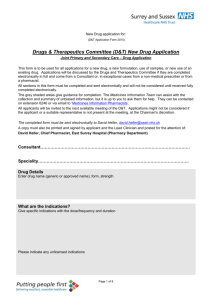

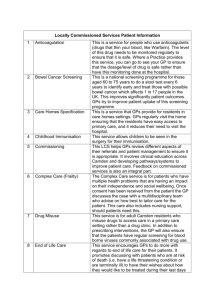

Prescribing Information Resources:Use and

advertisement