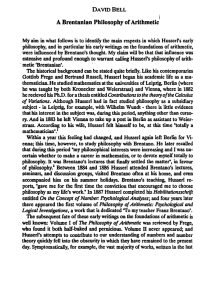

Husserl

advertisement

Husserl Phenomenology: Issues and Method The Challenge of Psychologism One of the things that Husserl joins Kant in affirming is the goal of developing philosophy as a science. Unlike Kant, however, Husserl faced a number of contemporaneous intellectual movements that cast significant doubt on the very possibility of such a development. The two most prominent ones were psychologism (and historicism.) Very early in his career, Husserl recognized (at least in part, due to the work of Frege) that he needed to definitively respond to the obstacles posed by these theories. So what is psychologism? In general, psychologism is the tendency to limit the explanation of human activity to psychological facts. At one level, this is a perfectly natural, and innocuous process. We often seek to understand the actions of the people around us by speculating on their psychological states. Other more or less innocent types of psychologistic interpretations are psychohistory and psychological interpretations of literature. The problem emerges when we extend the limited scope and value of such explanation to the whole of human experience. This is particularly dangerous when we attempt to reduce consciousness to mere psychological facts. On this understanding, psychologism is a species of naturalism (the attempt to explain consciousness and conscious experience on the basis of purely natural (though not necessarily physical) facts). This is much closer to the strict sense of the term psychologism that is Husserl's target: the attempt to reduce logic to psychology. Crudely put, the question that Husserl seeks to answer is: is logic, as a normative discipline, a species of psychology, or do its theoretical foundations lie elsewhere. Husserl is going to assert the latter, ultimately pointing to the ideal character of logic as the clue to its proper grounding. Let's take a closer look. Some Key Claims in Husserl’s rejection of psychologism: 1. Logic is a normative discipline. It's focus is not 'what' we think, or even 'how' as a fact we do think, but how we 'should' think. 2. As normative, logic is the science of the sciences. That is, it is the standard of thinking as such, and all reasoning in the specific sciences is constrained by this standard. 3. Logic, like any normative discipline requires a foundation in a theoretical discipline. As purely formal, it has no content itself, no way of accounting for the relationship between the ideal that it is and what it is an ideal for/of. Such an account can only be provided by a theoretical discipline. The question then is: which theoretical discipline provides this foundation for logic. As Husserl characterizes it, the argument in favor of psychologism has an intuitive strength that seems difficult to resist. What is logic a science of? Thinking. Where does thinking happen? In the mind. What is the science of the mind? Psychology. Even if we grant this to psychologism, at best what it establishes is that psychology has a role to play in the foundation of logic. They do not preclude the possibility that there is a realm of 'pure' logic that falls wholly outside of the sphere of psychology. It is this realm that Husserl is seeking to delimit. In general, Husserl opposes psychologism because of what he sees as its absurd consequences. They fall into two general categories. 1. Empiricistic: as a descriptive science, psychology is limited to the merely probable conclusions of induction. Yet logic is concerned, at least in part, with what is necessarily, and not merely probably, true. Psychologism cannot account for the absolute character of logic. 2. Skeptical: the attempt to reduce logic, to factual psychological laws threatens the absolute character of logic in another way. Namely, by asserting that logical laws are founded in contingent The fact that, in the face of these consequences, people still argue for psychologism is to be explained by a set of prejudices common not only to the advocates of psychologism, but to their opponents—prejudices which are so common precisely because they are deeply ingrained in everyday consciousness. 1. Rules guiding thought must be mental. However, when we consider the normative force of logical laws, what becomes apparent is that their content is not only prescriptive. That is, logic is not a 'rule book' for thinking. Rather, logic is a theory of truth. The psychologists make the mistake of confusing the subjective apprehension of the truth (which admits of a psychologistic interpretation) with the systematic unity of the truth thus apprehended. The latter is independent of any particular mode or style of apprehension and it is the task of 'pure' logic to grasp the principles of its systematicity as truth. Husserl insists that the mistake of the psychologist amounts to confusing the real for the ideal (the empiricistic error). 2. If, as the pshychologistic approach would suggest, we focus on the mental content of all logical judgments, any attempt to isolate a 'pure' logic would be fundamentally mistaken. Here, according to Husserl, psychologism oversteps itself. If this were true, not only would logic be grounded in psychology, but so would mathematics (thus raising the specter of skepticism). 3. The last refuge of psychologism is the assertions that logic is really nothing other than the 'inner certainty' of certain forms of judgement. Here too skepticism seems to be the obvious implication. Is the failure of such certainty to manifest itself to count against logical certainty itself? The key to all of these prejudices is a confusion between the real and the ideal. Psychologism collapses the ideal into the real, thus missing the ideal character of logic. It is this ideal character that for Husserl is the real object of logical reflection. The Natural Attitude as the Touchstone of Philosophy All philosophy starts in the "middle of things," in the context of our everyday concerns and perspectives. Husserl's term for this 'everyday' mode of existence is the 'natural attitude.' A first question to ask of any philosophy is, "What do you make of that starting point?" The answer to the question is crucial. For Husserl, an inadequate response is only slightly better than the failure to recognize the issue at all. The first step in adequately addressing the question is to thematize this everyday mode of existence. Husserl suggests that the best way to do this is to reflectively adopt the first person perspective. In this perspective, significant dimensions of the natural attitude are revealed. First, I find that I am in the world. This surrounding world (umwelt) is not formless or empty. It's filled with things and people that I am more or less immediately or directly concerned with. Of course, these things and people are not all immediately present to my faculties of perception. The field of my actual perception is accompanied by a "horizon of indeterminate actuality," a realm of possible perception that can be made actual by directing my consciousness towards it. Second, this world is not merely spatially determinate. The same sort of analysis could be provided for the temporal dimensions of my experience. The present is carried along in a penumbra of past and future experiences. For both dimensions of my experience, it is possible to imaginatively vary my standpoint, adopting a different place and different time. Significantly, such variation itself reveals the same horizonal structures revealed by my present perspective. Third, the umwelt is not merely a world of space and time. It is as immediately and naturally, a world of values, of practices, and these values and practices are not external to my involvements with the umwelt, but rather establish the very character of this involvement. The next step in our reflective assessment of the natural attitude is to consider the unity of these various dimensions of our everyday experience of the world. A brief consideration reveals that all of these various horizons are oriented around me (not me personally, but the reflective subject). The things I actually perceive now, and the things I only potentially perceive are there for me. The present is my present, and the past and the future that accompanies it are mine as well. The value and practical characteristics of the things and persons in the umwelt are determined by my situation. Husserl names the unity of these strata of sense the "Cogito" in a conscious invocation of Descartes. My experience of the world is always and constantly oriented by (intended) my active, conscious life—even when I am unreflective about that activity. I am always in the world in a particular way. The natural attitude is the most basic and ineliminable way I am in the world, but I can and often do adopt more limited and specialized attitudes to accomplish specific purposes (arithmetical attitude constitutes an arithmetical world). A particularly pervasive and important attitude/world is the intersubjective world. Fundamental to this world is the natural commitment to the objectivity of our shared world. In fact, Husserl ultimately argues that the sense "objectivity" requires this intersubjective world for its full expression. Given this variety of attitudes/worlds, an important question that still remains is what distinguishes the natural attitude and its world from other more specialized ones. Husserl responds by noting that the natural attitude is a pre-thetic attitude, that is, it is prior to and actually excludes any theoretical analysis. Before any consideration of what it means to characterize something as actually and factually existing, the natural attitude is our commitment to this sort of existence for the world of our experience. Husserl is now in a position to answer the question—what to make of the natural attitude? §31 begins with this answer, "Instead of remaining in this attitude, we propose to alter it radically.” The intent of this alteration remains obscure. What we first need to consider is the possibility of altering it. Remember, we've already noted that the natural attitude is an ineliminable component of our experience. We are from the first committed to the existence of the 'natural' world. However, the history of philosophy has shown that such a commitment (positing) can be put aside: Cartesian doubt is only one of the most thoroughgoing (and instructive) examples of this. What does Descartes' example reveal? The most important thing to recognize is that an interruption of the natural 'positing' of the world need not take the form of a counter 'positing.' That is, doubt is not denial. Rather, it is a form of "parenthesizing" of "bracketing." If we consider the relation of this bracketing to the natural attitude, we discover that it is a specific and particular mode of consciousness which accompanies, while modifying, this attitude. What precisely is modified? It is not the fact of our commitment to the 'truth' of the natural attitude. Rather, it is the tendency to extend that truth, through judgement, to a metaphysical commitment. What is bracketed or suspended is thus judgment. The next step is to delimit the phenomenological sense of this epoché. Husserl distinguishes this sense from both the sophistic (negation) or skeptical (doubting) modalities, which both retain an implicit judgement, insisting that all judgement has to be suspended (cf. 65c1-2). Two implications of the phenomenological epoché have to be noted. First, such suspension requires us to exclude from consideration as a possible foundation for philosophy the findings of the natural sciences taken as a valid determination of the natural world. I can of course bracket these propositions and consider them as the offer insight into my experience. Second, the epoché is not merely a methodological principle (like the positivist demand to purify the sciences of metaphysical elements). It is a radical reorientation of our conscious apprehension of the world (cf. 65c2).