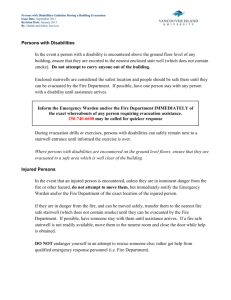

Emergency Evacuation of People With Physical Disabilities from

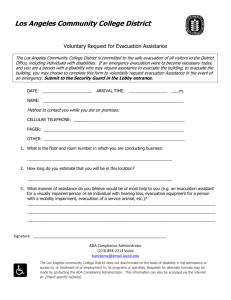

advertisement