Embodiment, Language, and Mimesis

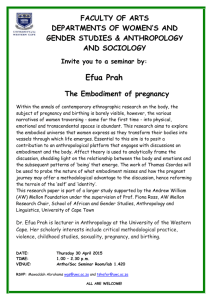

advertisement