Chapter Two: Origins of the Market Economy

advertisement

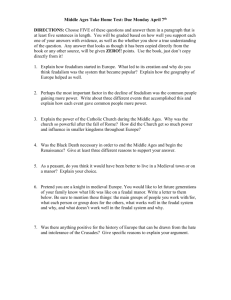

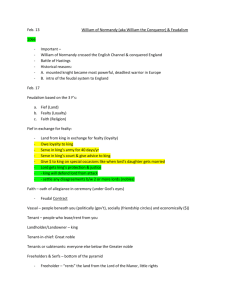

Chapter Two: Origins of the Market Economy "Thus [economics] is on the one side a study of wealth; and on the other and more important side, a part of the study of man. For man's character has been molded by his every-day work, and the material resources which he thereby procures, more than by any other influence unless it be that of his religious ideals; and the two great forming agencies of the world's history have been the religious and the economic." Alfred Marshall Both micro and macroeconomics are products of the capitalist culture. Economics as a discipline did not exist prior to the existence of the market economy. Economics as a system of ideas aspiring to describe how our economic system works originated and developed alongside market system itself. Microeconomics in particular legitimizes consumption as the end all of human existence. Maximizing consumption, of course, means maximizing production. At the macro level the objectives are complementary: promote economic growth to enhance the incomes of both individuals and governments alike. The notion of economic growth as a precondition for human happiness coincides with the most obvious feature of Western civilization: its affluence. Despite the varied cultures that exist today, the West dominates. With the collapse of the Soviet Empire, the command system as an alternative method for organizing an economy has lost its appeal. Capitalism has triumphed. Japan, which little more than a hundred and fifty years ago was a traditional society, made a conscious effort to follow the West and industrialize at the end of the last century. Japan, of course, is the most successful non-Western country to adopt Western values. But others are catching up. Peoples in third-world countries are abandoning their traditions, clearing their jungles, and developing their resources to embrace Western ways. Throughout the world television conveys an image of life in America to which many aspire: wealth without work, mindless consumption, and unbounded greed. What is the source of the West’s affluence? How did the West achieve a level of affluence unequaled in human history? Nobel Laureate Douglas North and Paul Thomas argue that affluence results from an efficient economic organization,1 a set of institutional arrangements that channel individual effort into activities conducive to economic growth. The institutional arrangement to which 1 Douglass C. North and Paul Thomas. The Rise of the Western World: A New Economic History. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1973. Origins of the Market Economy 18 North refers is known as the market economy, or more generally capitalism. By capitalism we mean both the market economy plus its associated culture. Markets versus Market Economy A market is not the same as a market economy. As places where buyers and sellers meet, markets have existed for thousands of years embedded in an otherwise traditional economy. In such economies markets are not the central institution upon which people depend. In such economies people produce the goods that they themselves consume. Nature provides sustenance, and people provide support. Markets exist as a means to dispose of surplus goods. In contrast, a market economy means subjecting human relations to market forces. This requires transforming nature and people into commodities, into something for purchase and sale. Human relations are governed by the laws of the market, not customs, not traditions, not some principle of social justice.2 Transforming nature and people into commodities requires separating the economic sphere from the religions sphere. The viewpoint is reflected in Bernard Mandeville’s comment that “trade is one thing, religion another.” For economics to emerge as a discipline separate from morality and law, economic relations had to become separate. This is why people in previous civilizations did not recognize economics as an independent discipline. The effort to create a market system invariably requires force. People seldom willingly forego the certainty of their previous life to engage in the uncertainty of another. This is why extending the market system to traditional peoples always leads to conflict. The problem in settling the American West was disposing of the Indians, in effect, removing them from the land. The same is true for harvesting the rain forests of Brazil, Malaysia, and other third world countries. The transformation of these natural resources into commodities means separating the indigenous populations from the means of production. The result: social dislocation, impoverishment, and conflict. The same was true at the birth of the market system. The transition from feudalism to capitalism required separating the means of production from the indigenous peoples. Happening so long ago, the effects of the separation are almost forgotten. But the market system was born of blood and tears. It represents a unique event in human history. 2 See Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation (New York: Rinehart), 1944. Origins of the Market Economy 19 Feudalism found its legitimacy in religion; the market system found its legitimacy on science. It is no coincidence that the laws of the market that the economists discovered are that same laws that Newton discovered in describing the cosmos. Were the laws of the market something inherent in society? Or were they in the air so to speak? Five-hundred years ago to charge interest on a loan was considered a sin against God punishable by eternal damnation. Dante placed the moneylender in the center of Hell, the voyeur he placed on the outskirts. Profit and interest were considered immoral. Today they are considered good business. Capitalist enterprise is not possible without capitalist values. People must be predisposed to earning profits. Profits must be acceptable, even desirable. In a society in which profit making and interest are considered immoral, business is not possible. Happening so long ago the transition from feudalism to capitalism is a dim memory in our collective consciousness. What was feudal society like? What factors were involved in its demise? And what gave rise to the capitalist system? Feudalism Feudalism existed in Western Europe approximately from 500 to 1600 AD. Feudalism is a traditional economic system, an economic system in which the rules for conduct are reflected in the traditions and customs of the people. The rules of conduct channel effort towards serving God, preparing for war, and general survival. Making money other than for the objectives mentioned was against the rules. The transition from feudalism to capitalism represents a revolution in both thought and practice. Serving God yielded to pursuing money. Production for one’s own use or use by the community gave way to producing goods for exchange. The personableness of community gave way to the impersonableness of markets. Under feudalism markets are subordinate to society. Under capitalism, society is subordinate to the market. Feudal society was divided into two classes: the feudal lord, the priests, and the knights on the one hand, and the serfs on the other. The customs and tradition of the manor governed the relations between them. The serfs paid rents in kind to the lord, payments in the form of goods or labor services. In return, the serfs received protection and justice. Each class had a particular function to perform, each was necessary to the whole. Society was compared to the human body: the feudal lords were the brains; the knights the hands to fight with, and the serfs the feet supporting the whole structure. Origins of the Market Economy 20 Unemployment did not exist. This is not to say that there was no poverty. Poverty was a characteristic of a group or a class, not an individual. Beggars, in fact, were viewed as opportunities to do good deeds. The attitude towards beggars reflects the purpose of feudal society: to serve God. Every activity had to be justified before the religion. Religious life permeated feudal society in ways that we cannot understand. Profit and interest were considered wrong in part because they appeared to take advantage of another's need, and hence contrary to the service of God. Private property did not exist, as we know it. The feudal lord owned the land as a steward. Ownership entailed rights and responsibilities, rights to the rents; and responsibilities to car for the serfs. Serfs too had rights, rights to use the land--cultivate the fields, tend the animals, and use the commons for hunting and gathering wood. Hence, serfs had direct access to the means of production. Factors involved in the Decline of Feudalism In the fourteenth century there was no indication that the West would emerge triumphant. The locus of civilizations was not in the West, but the East. The Byzantine Empire, located in modern Turkey and the Middle East, was in its ascendancy. Byzantine excelled in science, mathematics, and art. From them we received the institution of the university. China excelled in education, fine silks, and organization. Moreover, China’s wealth was evident in its silks, spices, and dress. The cities of Byzantium and China excelled in both beauty and cleanliness. How then did the West emerge triumphant? Marx contends that the demise of feudalism was the result of class struggle. The Feudal structure could no longer generate enough surplus to maintain the ruling classes. Henri Pirenne contends that the origin of capitalism lie in the emergence of long-distance trade. Max Weber finds the origins in new religions attitudes toward trade. To look for a single cause, however, is folly. Many rivulets, streams, and trickles merge to form the new civilization. What follows are some of the more notable trickles that subsequently formed a torrent. Long-distance Trade During the dark ages (500 - 1000 AD) Western Europe slumbered. The great cites of the Roman Empire were long since abandoned. People retreated into the countryside, swearing allegiance to a feudal lord in return for his protection. Goods and services produced locally were consumed locally. Trade for any distance was non-existent. Origins of the Market Economy 21 In the eleventh century Charlemagne launched the first of four crusades. The purpose of the crusades was to capture Jerusalem for Christianity. As a result, however, contact was made with the Eastern Mediterranean initiating the reemergence of trade. The emergence of trade gave rise to the cities of Flanders, Venice, and Antwerp--islands of capitalism in a feudal sea. The ensuing wealth that poured into the cities helped finance the Renaissance. Renaissance Renaissance means rebirth. The Renaissance originated in Italy in the thirteenth century, made possible by the donations of wealthy financiers. Initially, the purpose of the Renaissance was to create works of art and literature equal to those of ancient Greece and Rome. Ideologically, however, the Renaissance meant a decline of religious influence. Artists, for example, turned away from religious themes to paint people in every day activities. There are two important offshoots from the Renaissance that are particularly important for the rise of capitalism. First, the philosophy of humanism challenged the dominance of religion summed up in the humanist phrase "man is the measure of all things." And second, modern science challenged the ancient view stressing the harmony of nature. Science rests on the assumption that nature exists to be dominated and controlled. This assumption underlies the development of modern technology, which for good or bad has vastly increased our power over nature. Only recently has the threat of pollution and global warming questioned the scientific view of nature. Discovery of the New World The reemergence of trade occurred in the Mediterranean. Hence, the initial impetus to development occurred not in England, but in Italy. Italy was the centers of Western civilization in the 13th, 14th, and 15th centuries. After the discovery of the New World the center shifted to Holland. Trade with the East proceeded by boat from Italy to the middle east, and then over land to India and China. The Ottomans, however, realizing their monopoly over the trade routes in the middle east, increased their tolls. To satisfy Europe’s appetite for silks and spices the Portuguese found an alternative route around Africa. Columbus sought to find his route by heading west. In looking for India, or course, Columbus stumbled upon America. The two centuries that followed initiated the commercial revolution that changed the face of Europe and the world forever. The discovery of the New World had two major impacts. First, the Europeans pillaged the temples of the Aztec civilization, sending the precious metals back to Spain. From there the metals Origins of the Market Economy 22 flowed throughout Europe. The influx of the precious metals increased the money supply in Europe, which in turn resulted in inflation (a general rise in the price level). This in turn redistributed income to the emerging commercial classes. Second, contact with the Spanish decimated the Indians. The Spanish claimed their souls for heaven, and their bodies for work. But soon there were few Indians to claim. Estimates place the population of Mexico prior to the Discovery of the New world at 25 million. Fifty years after Cortez the population had shrunk to 3 million. By 1600 90% of the indigenous population had died from diseases introduced by the Europeans. The Spanish, of course, interpreted their deaths as divine punishment. Protestant Reformation The revolution in commerce forms the backdrop for the revolution in ideas. The Protestant reformation was an effort to reform the practices of the Catholic Church. Participants in the reformation found objectionable the practices of indulgences. One could sin all week, and by paying a simple fine have his sins washed away. The cycle of sin, repentance, and redemption became a source of abuse. This abuse came to a head when in 1515 the Pope expanded the indulgences in order to raise revenue for the Sistine Chapel. Luther objected vehemently. It is not by doing good deeds Luther argued that one achieves salvation, but by faith alone. People could no longer “buy” their way into heaven. Luther further challenged the authority of the Church itself, arguing that all men are brothers in the eyes of God. In the Catholic view, the priest is superior to the lay people. The priest’s superiority lay in his authority as the mediator of one’s relationship with God. He offered the sacrament, heard confessions, and taught the people God’s word. As one economic historian put it, “Luther destroyed the faith in authority by establishing the authority of faith.” The upshot of Luther’s ideas was to introduce a degree of religious individualism. Each person is responsible for his or her salvation, no one else. Another person participating in the Protestant reformation is John Calvin.3 First, Calvin enunciated the doctrine of predestination, the idea that God has already predetermined one's life. God has determined already one's fate: salvation or damnation. The problem, however, is that God’s plan remains unknown. The only indication of one's eternal fate is whether one has received God's 3 See for example Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons), 1958. Origins of the Market Economy 23 grace. An indication that one has received God’s grace is material prosperity. If things are going well, if prosperity reins, one is probably going to heaven; if not, hell. Wealth and poverty become a measure of one's moral character. Second, Calvin formulated the doctrine of the Calling. In feudal times the doctrine of the calling--the idea that one has been called by God to one's work--pertained only to church offices. Calvin generalized the concepts to all forms of work. One does not show his love for his fellow man through sentiment or emotion, but through hard work. To be a butcher, brewer, or baker is not merely a job. It is a calling. You have been called by God to cut meet, bake bread, or brew beer. Hence, you have a moral obligation to do it well. Over time the religions connotation underlying the calling was forgotten, but the psychological predisposition it created continued in force. Making money is no longer a sin, it is a duty to God. This marks the origin of the Protestant work ethic. The third doctrine is the doctrine of this-worldly asceticism. An ascetic is one who denies himself pleasure. The idea is that to consume, to enjoy life is inspired by the devil and hence evil. The implication is that one should deny oneself the pleasures of the flesh. Over time the religious meaning was forgotten, but the psychological predisposition continued in the idea that saving is a virtue. The doctrines of the Protestant Reformation took hold, in part, because they represented an ideology conducive to the accumulation of wealth. Profit and interest are no longer sins, but part of God’s divine plan. You cannot have capitalism without a capital stock. And you cannot accumulate a capital stock without many individuals working hard, while at the same time saving and investing the result of their work. The Enclosure Movement The commercial explosion brought about by the discovery of the new world offered many opportunities. In England the consolidation of the nation had occurred two centuries before. The serfs, once used as labor services and as soldiers, were no longer necessary. In earlier times the basis of wealth lay in the number of serfs in the kingdom, now it lay in the number of sheep. With the price of wool rising, feudal lords had an opportunity to make money. In response, they forcibly removed the serfs from the land. The lords enclosed the land with hedges and stone fences, and began raising sheep. The serfs, dispossessed of their traditional lands, crowded into the countryside. Origins of the Market Economy 24 Queen Elizabeth was shocked at the number of rogues and vagabonds. England's initial reaction was to outlaw it. Unlicensed beggars above 14 years of age are to be severely flogged and branded on the left ear unless someone will take them into service for two years; in case of a repetition of the offense, if they are over 18, they are to be executed, unless someone will take them into service for two years; but for the third offence they are to be executed without mercy as felons.4 When they realized that outlawing poverty did not eliminate it, the English passed the Poor laws. The Poor laws have gone through a lengthy evolution. But they represent Britain’s efforts to deal with poverty. In the very early years the attitude was that if poverty could not be abolished, at least make it profitable. Mercantilism (1600-1800) Many people believe that that the natural state of the economy is one in which government does not intervene. There is, however, no basis for this historically. Governments have always intervened. No where is this more evident than in the first stage of capitalism, known as Mercantilism. In the first blush of their youth the newly emerging commercial classes needed government. Governments offered protection, granted monopolies, opened new markets, fostered industries, and so on. Mercantilism represented a symbiotic relationship between government and business. Under feudalism government allied itself with the Church in trying to restrain self-interest. Under mercantilism government realized that by encouraging business, governments could increase their revenue. A thriving business community meant a thriving government. Mercantilists identified wealth with gold and silver. For nations such as England that found themselves without gold or silver mines the means to achieve wealth was to run a balance of trace surplus: that is, the value of exports exceed the value of imports. This in turn required the regulation of business to ensure that they did not import goods from abroad, and to ensure that they promoted exports. Economic relations where conceived as a zero-sum game. One country’s gain was another country’s loss. Hence, in contrast to Adam Smith economic relations were seen as conflictual. Colonization initially represented an effort to provide raw materials such as tobacco, cotton, cocoa, sugar, labor and so on. Only later when a portion of the people had sufficient income could the colonies serve as a vent for disposing of the surplus production of the industrial countries. 4 Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1, (New York: Vintage Books), 1976, pp. 897-98. Origins of the Market Economy 25 The turmoil of the 16th and 17th centuries must be looked in light of the mercantilist policies. The European nations were trying to expand their realm of influence in the pursuit of gold. The result was war, conflict, and the forcible subjugation of the indigenous peoples of the world. Laissez Faire or Market Capitalism (1800-1930s) By the late eighteenth century the Industrial Revolution swept away the old system, and created a new system: laissez faire or market capitalism. The Industrial Revolution is heralded by the introduction of machines into the workplace. The mercantilist system of regulations interfered with the increased supply of goods, and the increased demand for inputs. In brief, business interests needed to be set free. Prior to the Industrial Revolution manufacturing had to be located on waterways. A water wheel was used to run machines, grind grain, and so on. All over Europe small manufactories sprouted along the waterways. The invention of the steam engine, freed manufacturing from having to locate along water ways. Production was characterized by what is know as the putting out system. Skilled craftsman working in their homes performed most production prior to the Industrial Revolution. The capitalists brought them the raw materials and picked up the finished products. The craftsman, for the most part, owned their own tools, set their own time, and worked at their own pace. Production became a family matter, with each part of the household contributing. The Industrial Revolution changed all that. First, the Industrial Revolution meant new innovations based on the steam engine; new machines for processing cotton, for transforming that cotton into cloth, and so on. This in turn manifested itself in a decline in the price of capital relative to labor. Capitalists responded by substituting capital for labor. The skilled craftsmen were no longer needed, resulting in an increase in poverty. Second, the new type of production altered they type of labor needed. Machines simplified the labor process by dividing up the tasks. One person performed one task, another person another task. This extended division of labor reduced the demand for skilled labor, and increased the demand for unskilled labor. But the increase in the demand for skilled labor was insufficient to restore full employment. Third, the demand for unskilled labor meant in general a decline in pay. In many cases women and children were preferred. The first effort to regulate the use of child labor—in effect Origins of the Market Economy 26 protect children from market forces--was met with hostility. Business owners responded that this is my property. Who are you to tell me what to do? Fourth, the Industrial Revolution introduced the factory system. The capitalist no longer took the raw materials to a craftsman. The new system enabled the capitalist to control all aspects of the work process. He could now hire workers, bringing them under one roof; regulating the times they began work; and when they ended. Working conditions were generally horrible: the machines were loud; lighting was poor; hours were long and arduous. Another by product of the factory system is that relations between workers and the capitalist became impersonal. The Industrial Revolution, however, was not a total disaster for workers. By the late nineteenth century incomes actually rose. The welfare of many working people, at least those in the developed world, actually improved. Internationally, the market economy became a worldwide phenomenon. Britannia, unequivocally the master of the seas, needed access to markets to feed its growing industries. And access to markets meant free trade, which Britain was quick to enforce. As noted, a market economy means the subjection of human beings to market forces. The market economy imposes a particular form of motivation, namely, the promise of profit and the threat of hunger. At no time in human history has their been a more efficient form of human motivation. In the past it was thought that people had to be coerced to do what was in society’s interest. Adam Smith said let them be free. “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”5 If Smith promised profit, however, Malthus promised pain. Evil exists in the world not to create despair but activity. We are not patiently to submit to it, but to exert ourselves to avoid it. It is not only the interest but the duty of every individual to use his utmost efforts to remove evil from himself and from as large a circle as he can influence, and the more he exercises himself in this duty, the more wisely he directs his efforts, and the more successful these efforts are, the more he will probably improve and exalt his own mind and the more completely does he appear to fulfill the will of his Creator.6 5 Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (New York: The Modern Library), 1937, p. 13. 6 T. R. Malthus, Principles of Political Economy (London: John Murray), 1820, p. 217. Origins of the Market Economy 27 Historically, laissez faire represents a conscious decision on part of governments not to intervene. In brief, laissez faire was planned. But the decision not to intervene was met with an almost spontaneous counter movement demand that governments intervene in order to protect human beings from market forces. The culmination of this effort manifests itself in the emergence of the corporate, welfare state or what is sometimes referred to as the mixed economy. Corporate, Welfare State (1930s-) The corporate, welfare state has its origins in two sources. First, the merger movement of the late nineteenth century led to the emergence of the corporation century as the dominant form of business enterprise. Corporation arose in part as a means of controlling ruinous competition that had bankrupted so many businesses. And second, the welfare state has its origins in the effort on part of governments to provide economic security. The depressions of the nineteenth and early twentieth became politically unacceptable. The artificial separation between the economic and political spheres erected by the policy of laissez faire quickly fell. People voted for bailouts. And bailouts require government intervention. The specific events, however, that spelled the demise of the laissez faire capitalism began in 1917. World War One shattered the tranquillity of the market economy. Referred to at the time as the war to end all wars, World War One resulted from the efforts on part of the industrialized powers of Europe to obtain resources. In brief, it was a capitalist war. The First World War, ensuing depression of the 1930s, and the Second World War that followed represent a single revolution in the global economy. The second great event was the Russian Revolution, the product of blood shed by people in the hopes of creating a better world. The rise of totalitarianism both in Russia and Germany was a response to the problems and issues created by the market economy: poverty, depression, and so on. By the end of the twentieth century the great wars that consumed so many lives and wasted so many resources appear ended. And the great experiment in central planning has proved a failure. The problem for the former centrally planned societies is how to create a market economy. But the problem with the market economy continues to vex, namely, how do we motivate people to do that which is in society’s interest? How do we create social and economic institutions that channel individual choices into social desirable outcomes? The clue perhaps lies in the economists view of human motivation, namely, the concept of rational choice, which forms the very heart of microeconomics. Origins of the Market Economy 28 Review Questions I. What is the most obvious characteristic of the West? II. Distinguish between a market and a market economy? III. Define feudalism. How does feudalism differ from capitalism? IV. What are five factors involved in the emergence of capitalism? V. What is mercantilism? VI. How are the policies underlying mercantilism consistent with the ethos associated with the Protestant Reformation? VII. What is laissez faire or market capitalism? VIII. What is the corporate, welfare state?