Rustic Speech and Folklore

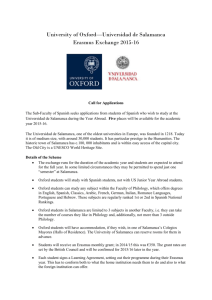

advertisement