DOC - San Jose State University

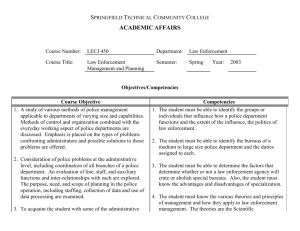

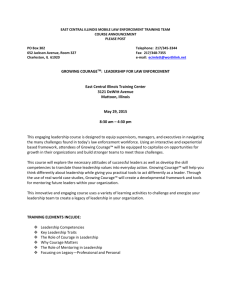

advertisement