Consumers First_Smart Regulation for Digital Australia

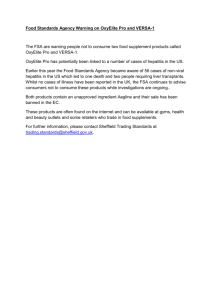

advertisement